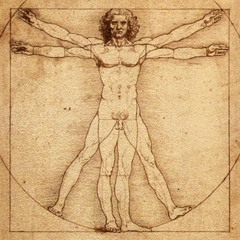

symbol for the Renaissance, math, science coming together to form perfection of realism, summary of everything Leonardo believed

triumphal arch frames the apse, which has seats for clergy and a throne in the center for the bishop.

reduces weight at a critical point. Originally constructed on the ruins of an earlier tem- ple, the Pantheon was at one end of a columned square. As in other Roman temples, a flight of steps leads to the portico.

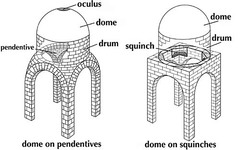

A dome (from Latin: domus) is an architectural element that resembles the hollow upper half of a sphere. The precise definition has been a matter of controversy. There are also a wide variety of forms and specialized terms to describe them. A dome can rest upon a rotunda or drum, and can be supported by columns or piers that transition to the dome through squinches or pendentives. A lantern may cover an oculus and may itself have another dome.

Italian renaissance domes were designed to capture the humanistic principles of the Renaissance. Architects during the renaissance wanted to capture emotion and reason in their work. They also attempted to reach ideal proportions, thinking in line of the human body. The domes were inspired by Greek and Roman architecture. The three notable architects during the Italian renaissance were Filippo Brunelleschi, Leon Battista Alberti, and Andrea Palladio. Italian renaissance domes were first developed in Florence and were soon spread all over various Italian cities.

Prior to the pendentive’s development, the device of corbelling or the use of the squinch in the corners of a room had been employed. Pendentives were commonly used in Orthodox, Renaissance, and Baroque churches, with a drum with windows often inserted between the pendentives and the dome. The first experimentation with pendentives was made in Roman dome construction beginning in the 2nd-3rd century AD,[3] while full development of the form was achieved in the 6th-century Eastern Roman Hagia Sophia at Constantinople.[4]

Born in Florence, Robbia was the son of Marco della Robbia, whose brother, Luca della Robbia, popularized the use of glazed terra-cotta for sculpture. Andrea became Luca’s pupil, and was the most important artist of ceramic glaze of the times.

He carried on the production of the enamelled reliefs on a much larger scale than his uncle had ever done; he also extended its application to various architectural uses, such as friezes and to the making of lavabos, fountains and large retables.

One of the most remarkable works by Andrea is the series of medallions with reliefs of the Infant Jesus in white on a blue ground set on the front of the foundling hospital in Florence. These child-figures are modelled with skill and variety, no two being alike. Andrea also produced, for guilds and private persons, a large number of reliefs of the Madonna and Child varied with much invention. These are frequently framed with realistic yet decorative garlands of fruit and flowers painted with coloured enamels, while the main relief is left white.

In the earlier Byzantine churches, the dome rested direct on the pendentives and the windows were pierced in the dome itself; in later examples, between the pendentive and the dome an intervening circular wall was built, in which the windows were pierced, and this is the type which was universally employed by the architects of the Renaissance, of whose works the best-known example is St. Peter’s Basilica at Rome. Other examples of churches of this type are St Paul’s Cathedral in London, and the churches of the Les Invalides, the Val-de-Grâce, and the Sorbonne in Paris.

Bracket, in architecture, device of wood, stone, or metal that projects from or overhangs a wall to carry a weight. It may also serve as a ledge to support a statue, the spring of an arch, a beam, or a shelf. Brackets are often in the form of volutes, or scrolls, and can be carved, cast, or molded. They are sometimes entirely ornamental. Among the types of bracket are the corbel and the console, but there are many types that have no special name.

A bracket acts simultaneously outward, along the horizontal or top edge, and downward along the wall that supports the vertical. Too great a load on the bracket may pull dangerously against the wall, and so the horizontal edge is often an extension of an interior floor, to counteract the outward tendency. Such a design may be seen in the Canon’s Cloister, Windsor Castle, New Windsor, Berkshire, England (1353-56).

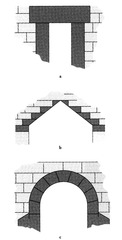

A false arch constructed by corbeling courses from each side of an opening until they meet at a midpoint where a capstone is laid to complete the work. The stepped reveals may be smoothed, but no arch action is effected.

A corbel arch consists of two opposing sets of overlapping corbels, resembling inverted staircases, which meet at a peak and create a structure strong enough to support weight from above. Babylonian architecture made wide use of corbel arches. When such arches are used in a series, they become a corbel vault, which, as in the Mayan style, can support a roof or upper story. Corbel vaults and arches were useful in cultures that had not yet developed curving arches and other ceiling structures. Structural corbeling has fallen out of general use in contemporary architecture.

spiral scrolls, characteristic of Ionic capitals and also used in Corinthian and composite capitals

It tends to evolve over time to reflect the environmental, cultural, technological, economic, and historical context in which it exists. While often difficult to reconcile with regulatory and popular demands of the five factors mentioned, this kind of architecture still plays a role in architecture and design, especially in local branches.

Vernacular architecture can be contrasted against polite architecture which is characterized by stylistic elements of design intentionally incorporated for aesthetic purposes which go beyond a building’s functional requirements. This article also covers the term traditional architecture, which exists somewhere between the two extremes yet still is based upon authentic themes.[1]

Vernacular architecture, a category of architecture based on local needs and construction materials, andraditional architecture of the world.

Vernacular art is made by countryside, often indigenous, people

Vernacular culture, cultural forms made and organised by ordinary, often indigenous people

The piano nobile is often the first (European terminology, 2nd floor in US terms) or sometimes the second storey, located above a ground floor (often rusticated) containing minor rooms and service rooms. The reasons for this were so the rooms would have finer views, and more practically to avoid the dampness and odors of the street level. This is especially true in Venice where the piano nobile of the many palazzi is especially obvious from the exterior by virtue of its larger windows and balconies and open loggias. Examples of this are Ca’ Foscari, Ca’ d’Oro, Ca’ Vendramin Calergi, and Palazzo Barbarigo.

Larger windows than those on other floors are usually the most obvious feature of the piano nobile. Often in England and Italy the piano nobile is reached by an ornate outer staircase, which negated the need for the inhabitants of this floor to enter the house by the servant’s floor below. Kedleston Hall is an example of this in England, as is Villa Capra in Italy.

Most houses contained a secondary floor above the piano nobile which contained more intimate withdrawing and bedrooms for private use by the family of the house when no honoured guests were present. Above this floor would often be an attic floor containing staff bedrooms.

A portico (from Italian) is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in Ancient Greece and has influenced many cultures, including most Western cultures.

Some noteworthy examples of porticos are the East Portico of the United States Capitol, the portico adorning the Pantheon in Rome and the portico of University College London. Porticos are sometimes topped with pediments.

Composed of columns and a pediment, it replicates the main façade of a temple; may be used decoratively or to form a porch or portico.

an architectural feature which is a covered exterior gallery or corridor usually on an upper level, or sometimes ground level. The outer wall is open to the elements, usually supported by a series of columns or arches. Loggias can be located either on the front or side of a building and are not meant for entrance but as an out-of-door sitting room.[1][2][3]

From the early Middle Ages, nearly every Italian comune had an open arched loggia in its main square which served as a “symbol of communal justice and government and as a stage for civic ceremony”.[4]

Fresco (plural frescos or frescoes) is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly-laid, or wet lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaster, the painting becomes an integral part of the wall. The word fresco (Italian: affresco) is derived from the Italian adjective fresco meaning “fresh”, and may thus be contrasted with fresco-secco or secco mural painting techniques, which are applied to dried plaster, to supplement painting in fresco. The fresco technique has been employed since antiquity and is closely associated with Italian Renaissance painting.[1][2]

The Palladian, Serlian, or Venetian window features largely in Palladio’s work and is almost a trademark of his early career. It consists of a central light with semicircular arch over, carried on an impost consisting of a small entablature, under which, and enclosing two other lights, one on each side, are pilasters. In the library at Venice, Sansovino varied the design by substituting columns for the two inner pilasters. To describe its origin as being either Palladian or Venetian is not accurate; the motif was first used by Donato Bramante[7] and later mentioned by Sebastiano Serlio (1475-1554) in his seven-volume architectural book Tutte l’opere d’architettura et prospetiva expounding the ideals of Vitruvius and Roman architecture, this arched window is flanked by two lower rectangular openings, a motif that first appeared in the triumphal arches of ancient Rome. Palladio used the motif extensively, most notably in the arcades of the Basilica Palladiana in Vicenza. It is also a feature of his entrances to both Villa Godi and Villa Forni Cerato. It is perhaps this extensive use of the motif in the Veneto that has given the window its alternative name of the Venetian window; it is also known as a Serlian window. Whatever the name or the origin, this form of window has probably become one of the most enduring features of Palladio’s work seen in the later architectural styles evolved from Palladianism.[8] According to James Lees-Milne, its first appearance in Britain was in the remodeled wings of Burlington House, London, where the immediate source was actually in Inigo Jones’s designs for Whitehall Palace rather than drawn from Palladio himself.[9]

A variant, in which the motif is enclosed within a relieving blind arch that unifies the motif, is not Palladian, though Burlington seems to have assumed it was so, in using a drawing in his possession showing three such features in a plain wall (see illustration of Claydon House right). Modern scholarship attributes the drawing to Scamozzi. Burlington employed the motif in 1721 for an elevation of Tottenham Park in Savernake Forest for his brother-in-law Lord Bruce (since remodelled). Kent picked it up in his designs for the Houses of Parliament, and it appears in Kent’s executed designs for the north front of Holkham Hall.[10]

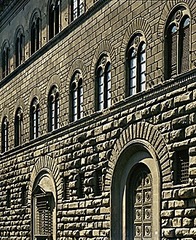

Palazzo style refers to an architectural style of the 19th and 20th centuries based upon the palazzi (palaces) built by wealthy families of the Italian Renaissance. The term refers to the general shape, proportion and a cluster of characteristics, rather than a specific design; hence it is applied to buildings spanning a period of nearly two hundred years, regardless of date, provided they are a symmetrical, corniced, basemented and with neat rows of windows. “Palazzo style” buildings of the 19th century are sometimes referred to as being of Italianate architecture but this term is also applied to a much more ornate style, particularly of residences and public buildings.

While early Palazzo style buildings followed the forms and scale of the Italian originals closely, by the late 19th century, the style was more loosely adapted and applied to commercial buildings many times larger than the originals. The architects of these buildings sometimes drew their details from sources other than the Italian Renaissance, such as Romanesque and occasionally Gothic architecture. In the 20th century, the style was superficially applied, like the Gothic revival style, to multi-storey buildings. In the late 20th and 21st century some Postmodern architects have again drawn on the palazzo style for city buildings.

Rusticated masonry is usually “dressed”, or squared off neatly, on all sides of the stones except the face that will be visible when the stone is put in place. This is given wide joints that emphasize the edges of each block, by angling the edges (“channel-jointed”), or dropping them back a little. The main part of the exposed face may worked flat and smooth or left or worked with a more or less rough or patterned surface. Rustication is often used to give visual weight to the ground floor in contrast to smooth ashlar above. Though intended to convey a “rustic” simplicity, the finish is highly artificial, and the faces of the stones often carefully worked to achieve an appearance of a coarse finish.[2]

Rustication was used in ancient times, but became especially popular in the revived classical styles of Italian Renaissance architecture and that of subsequent periods, above all in the lower floors of secular buildings. It remains in use in some modern architecture.

stringcourse, in architecture, decorative horizontal band on the exterior wall of a building. Such a band, either plain or molded, is usually formed of brick or stone. The stringcourse occurs in virtually every style of Western architecture, from Classical Roman through Anglo-Saxon and Renaissance to modern.

Often the stringcourse is used as a line of demarcation between the stories of a multistoried building. It is also used, especially in classical and neoclassical works, as an extension of the upper or lower horizontal line of a bank of windows. Examples may be seen on the Pantheon, built in Rome in the 2nd century ad; on many palaces of Renaissance Italy, including the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi (1444-59) and the Palazzo Strozzi (1489-1539), both in Florence; and on various manor houses in the English Renaissance style of the mid-16th to early 19th centuries.

Most frequently quoins are toothed, set in a regular pattern of alternating lengths. Such toothed construction was used at external corners of brick or stone buildings in ancient Rome. In 17th-century France, quoins were heavily rusticated, their surfaces roughened and their joints recessed. Similar treatment was used around wall openings (windows, doorways, and arches).

Occasionally quoins are dressed, smooth stones to contrast with walls of rough rubble masonry. They may also be of massive size, as in some Italian Renaissance palaces. Quoins in some brick buildings are covered with plaster, which accounts for the sharp contrast between the stark white quoins and dark brick walls of many manor houses built in the English Renaissance style.

Courtyards—private open spaces surrounded by walls or buildings—have been in use in residential architecture for almost as long as people have lived in constructed dwellings. The courtyard house makes its first appearance ca. 6400-6000 BC (calibrated), in the Neolithic Yarmukian site at Sha’ar HaGolan, in the central Jordan Valley, on the northern bank of the Yarmouk River, giving the site a special significance in architectural history.[1] Courtyards have historically been used for many purposes including cooking, sleeping, working, playing, gardening, and even places to keep animals.

Before courtyards, open fires were kept burning in a central place within a home, with only a small hole in the ceiling overhead to allow smoke to escape. Over time, these small openings were enlarged and eventually led to the development of the centralized open courtyard we know today. Courtyard homes have been designed and built throughout the world with many variations.

Courtyard homes are more prevalent in temperate climates, as an open central court can be an important aid to cooling house in warm weather. However, courtyard houses have been found in harsher climates as well for centuries. The comforts offered by a courtyard—air, light, privacy, security, and tranquility—are properties nearly universally desired in human housing.

There are in fact a variety of different terms used in contemporary records for chests, and the attempts by modern scholars to distinguish between them remain speculative, and all decorated chests are today usually called cassoni, which was probably not the case at the time. For example, a forziere probably denoted a decorated chest with a lock.[1]

Since a cassone contained the personal goods of the bride, it was a natural vehicle for painted decoration commemorating the marriage in heraldry and, when figural painted panels began to be included in the decor from the early quattrocento, flattering allegory. The side panels offered a flat surface for a suitable painting, with subjects drawn from courtly romance or, much less often, religious subjects. By the 15th century subjects from classical mythology or history became the most popular. Great Florentine artists of the 15th century were called upon to decorate cassoni, though as Vasari complains, by his time in the 16th century, artists thought such work beneath them. Some Tuscan artists in Siena and Florence specialized in such cassone panels, which were preserved as autonomous works of art by 19th century collectors and dealers, who sometimes discarded the cassone itself. From the late 1850s, neo-Renaissance cassoni were confected for dealers like William Blundell Spence, Stefano Bardini or Elia Volpi in order to present surviving cassone panels to clients in a more “authentic” and glamorous presentation.[2]

A typical place for such a cassone was in a chamber at the foot of a bed that was enclosed in curtains. Such a situation is a familiar setting for depictions of the Annunciation or the Visitation of St. Anne to the Virgin Mary. A cassone was largely immovable. In a culture where chairs were reserved for important personages, often pillows scattered upon the floor of a chamber provided informal seating, and a cassone could provide both a backrest and a table surface. The symbolic “humility” that modern scholars read into Annunciations where the Virgin sits reading upon the floor, perhaps underestimates this familiar mode of seating.

At the end of the 15th century, a new classicising style arose, and early Renaissance cassoni of central and northern Italy were carved and partly gilded, and given classical décor, with panels flanked by fluted corner pilasters, under friezes and cornices, or with sculptural panels in high or low relief. Some early to mid-sixteenth-century cassoni drew their inspiration from Roman sarcophagi (illustration, right). By the mid-sixteenth century Giorgio Vasari could remark on the old-fashioned cassoni with painted scenes, examples of which could be seen in the palazzi of Florentine families.[3]

The most important piece of furniture used in the home was the chest, or cassone (Figure 4.30).

Renaissance versions of the medieval chest resembled Roman sarcophagi, and were decorated with classical figures rather than heavy iron strapping and crude carvings. These chests were often placed at the foot of the bed and were used to store family valuables as well as clothing.

Cassones or chests (Fig. 12-22), used for storing possessions and seating, are the most important storage pieces and come in various shapes and sizes. Design and decoration vary according to intended use, such as wedding gifts, and wealth. Some have cartouches carved with the owner’s coat of arms or initials. Large ones may rest on animal feet.

Derived from both the Roman lectus with fulcrum armrests and the medieval box-form settle, the cassapanca became the prototype for the modern sofa. Made entirely from wood, the cassapanca was attached to its own dais, had arms on both ends, and had a hinged seat that could be raised to access a concealed storage compartment. This piece was not upholstered, but like the settle had loose cushions on both back and seat.

16th-century Italian cassapanca re- sembles the design of the Roman lectus in form, with its fulcrum-shaped arms and raised seat (Figure 4.27). Like the lectus, the cassapanca would be covered with loose cushions to make it more comfortable, although its design did not support reclining, but sitting, like a modern-day sofa.

long wooden bench with a seat and back and storage beneath the seat. Introduced in the mid-15th century in Florence, the cassapanca is sometimes placed on a dais at the end of a room to emphasize importance.

A cassone that has been provided with a high panelled back and sometimes a footrest, for both hieratic and practical reasons, becomes a cassapanca (“chest-bench”). Cassapanche were immovably fixed in the main public room of a palazzo, the sala or salone. They were part of the immobili (“unmoveables”), perhaps even more than the removable glazed window casements, and might be left in place, even if the palazzo passed to another family .

This drawing of a cassapanca from the 16th century features a scrolled pediment of reclining classical nudes. A loose cushion placed on top of the seat would have made the piece more comfortable.

box-form armchair, called a sedia, generally replaced these large-scale ceremonial chairs and was much smaller in size, although still rectangular in design. Sedias had velvet or tapestry upholstery that often featured fringe, or were upholstered in tooled leather. Finials carved into various shapes extended from the uprights, and squared legs with bracket or paw feet were con- nected front to back with runners or stretchers. This chair was used on a more formal basis in the refectory, or dining room. A sedia was positioned at each end of the table during the meal, and was placed against the wall while not in use.

Armchairs are rare before the 16th century, but by the end of the century, they are used in most rooms, al- though not in great numbers. Some grand dining spaces have sets of armchairs. Size denotes high status—the larger the chair, the higher the sitter’s status. Arm supports and front legs may be quadrangular or turned. Runners and/or stretchers may connect legs. Sometimes beneath the seat is an elaborately carved stretcher. Leather or fabric backs and seats may be trimmed with fringe and attached with nails. Decoration, usually carving, becomes more elaborate as the period progresses.

tiple wooden staves in an X-form configuration that collapses

lengthwise for easy mobility.

Similar in shape to Dantesque Chair, Savonarola, was designed to fold. The name of this chair pays homage to the 16th-century friar who was unpopular with the Florentines and the powerful Medici family. Friar Savonarola was burned at the stake in 1498. These chairs were made from walnut and had multiple staves that enabled the chair to fold lengthwise (Figure 4.25). The crest rail was hinged on one side and clamped into place on the opposite side, maintaining the stability of the chair when it was open. In a less decorative form, the chair was popular among monks and friars, which is probably how the chair became known by the name of the infamous friar.

folding chairs of X-form

Dantesca An upholstered Italian armchair having a short back, open sides, and an X-form base. Dantesca is also referred to as

a Dante chair named for the 14th-century Italian poet.

Another popular upholstered chair, the Dantesca, was named for the Italian Renaissance poet Dante. This chair was designed with front and back staves that were of the X form, although the chair did not fold (Figure 4.24). The two curule-form staves were connected with runners that usually had front-facing paw feet. A broad, upholstered crest rail served as the back support. Although some Dantescas had classical details carved on the frame, others were decorated with intarsia or certosina.

sgabello, which evolved from these types of stools, had a small, triangular backrest attached to the trestle-supported seat (Figure 4.22). Although these chairs were quite uncomfortable, they were small enough to be moved from the bedroom into the dining hall when necessary. Women usually sat in these chairs because the absence of arms accommodated their cumbersome skirts. Many were fitted with a single drawer under the seat that was used for storing sewing yarns.

sgabello or stool chair used for dining (Fig. 12-19). Armchairs and side chairs have quadrangular or turned legs with side runners terminating in lion’s heads. Back legs form the back uprights, and front arm posts form the front legs. Some have carved stretchers beneath the seat.

Trestle A type of support used on chairs and tables in the place of traditional legs.

During the Renaissance period, dining took place in a room used exclusively for eating, and a more permanent table was designed to

FIGURE 4.25 This walnut Savonarola is all wood with no upholstery, and its X-form base with multiple staves allows for remain in the center of the room. The refectory table was similar in design to the medieval trestle table; however, its long and narrow top was securely attached to a supporting framework, often two trestlelike ends connected with a stretcher (Fig- ure 4.28). Also, as threat of assassination lessened, people sat on both sides of the table seated on sedias, sgabellos, stools, or benches. When the table was not in use, the seating furniture was either placed against the wall or returned to the rooms

FIGURE 4.28 The banquet room from the Palazzo Davanzati in Florence features an Italian Renaissance-style refectory table carved with large paw feet. A long credenza can be seen against the back wall. © Scala/Art Resource, NY.

from which they were borrowed. In homes of the very wealthy, tapestries or Turkish carpets were often used as table covers.

Table with a flat leaf or leaves that extend from beneath the tabletop to increase the size of the table.

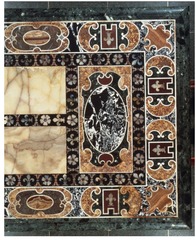

ble, hard minerals, or semiprecious stones inlaid in wood; used on table- tops and in panels during the Italian Renaissance; because of expense, production limited mostly to Milan and Florence.

Literally translated from the Italian, “hard stone” refers to colored marble mosaic.

Pietra dura—inlay using marble, granite, and other semiprecious stones—created beautiful mosaic botanical patterns on tabletops and cabinet doors.

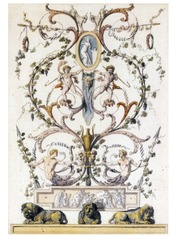

First revived in the Renaissance by the school of Raphael in Rome, the grotesque quickly came into fashion in 16th-century Italy and became popular throughout Europe. It remained so until the 19th century, being used most frequently in fresco decoration. Although the animal heads and other motifs sometimes have heraldic or symbolic significance, grotesque ornaments were, in general, purely decorative.

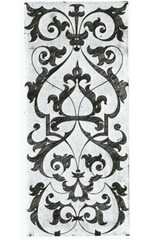

Arabesques are a fundamental element of Islamic art but they develop what was already a long tradition by the coming of Islam. The past and current usage of the term in respect of European art can only be described as confused and inconsistent. Some Western arabesques derive from Islamic art, but others are closely based on Ancient Roman decorations. In the West they are essentially found in the decorative arts, but because of the generally non-figurative nature of Islamic art, arabesque decoration is there often a very prominent element in the most significant works, and plays a large part in the decoration of architecture.

The portable sanctuary in which the Hebrews carried the ark of the covenant through the desert until the building of the Temple of Jerusalem by Solomon.

Liturgical furniture in a Catholic church to contain the ciborium

An ornamented receptacle in the church in which the consecrated Eucharist is reserved for Communion for the sick and dying as well as for adoration. In Israelite history, the tabernacle was the curtained tent containing the Ark of the Covenant and other sacred items. This portable sanctuary was taken throughout their wandering in the wilderness until the building of the Temple in Jerusalem.