Nambia. c. 25000-25300 B.C.E. Charcoal on stone

The earliest history of rock painting and engraving arts in Africa. The oldest known of any kind from the African continent.

Lascaux, France. Paleolithic Europe. 15000-13000 B.C.E. Rock Painting

represents the earliest surviving examples of the artistic expression of early people. Shows a twisted perspective.

Tequixquiac, central Mexico. 14000-7000 B.C.E. Bone.

The shape was created by using subtractive techniques and utilizing already apparent features in the bone, like the holes for eyes. It was a first look at how people began manipulating their environment to created what they wanted.

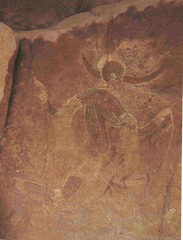

Tassili n’Ajjer, Algeria. 6000-4000 B.C.E. Pigment on rock.

The painting shows great contrast between the dark and light mediums used. There is also great detail put into the decorations of the woman. Most interestingly, though, there is a transparency to the larger woman and the figures behind her show through.

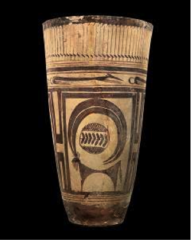

Susan, Iran. 4200-3500 B.C.E. Painted terra cotta.

One of the first ceramic pieces, made from clay and intricately designed with mineral and plant paint in painstaking detail. The vessel portrays a Ibex, a type of goat native to the area, and also canine figures along the rim. At the time, dogs were used to hunt animals like Ibexes. The painting might have been done with small brushes made from plant material or human or animal hair

Arabian Peninsula. Fourth millennium B.C.E. Sandstone.

Very stylized representation of a human figure, carved from stone. Has a make image and carries knives in sheaths across the chest and a knife tucked into a belt.

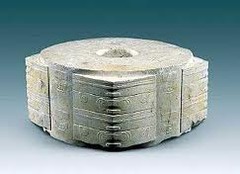

Liangzhu, China. 3300-2200 B.C.E. Carved jade.

Like one of many, this was a jade piece with decorative carvings, unique shape, and symbolic purpose. The stone might have held spiritual or symbolic meanings to the early cultures of China.

Wiltshire, U.K. Neolithic Europe. c. 2500-1600 B.C.E. Sandstone

Stonehenge is a famous site know for its large circles of massive stones in a seemingly random location as well as the mystery surrounding how and why it was built. The stones are believed to be from local quarries and farther off mountains. There is also evidence of mud, wood, and ropes assisting in the construction of the site.

Ambum Valley, Enga Province, Papua New Guinea. c. 1500 B.C.E. Greywacke

This is a sculpture of some sort of anteater-like creature made from a very rounded stone. With intense use of subtractive sculpting, this piece achieves a freestanding neck and head while still maintaining much of the original shape of the stone. It still uses natural materials and depicts a natural animal.

Central Mexico, site of Tlatico. 1200-900 B.C.E. Ceramic

The piece also stands as foreshadowing of the great civilizations that develop in south and meso-america and the art that is produced.

Lapita. Solomon Islands, Reef Islands. 1000 B.C.E. Terra cotta (incised)

One of the first examples of the Lapita potter’s art, this fragment depicts a human face incorporated into the intricate geometric designs characteristics of the Lapita ceramic tradition.

Uruk (modern Warka, Iraq). Sumerian. c. 35000-3000 B.C.E. Mud Brick.

Rooms for different functions. Cella (highest room) for high class priests and nobles.

Very geometric (4 corners of structure facing in cardinal directions) Platform stair stepped up

Pre-dynastic Egypt. c. 3000-2920 B.C.E Greywacke

Egyptian archelogical find, dating from about the 31st century B.C, containing some of the earliest hieroglyphic inscription ever found.

Sumerian. c. 2700 B.C.E. Gypsum inland with shell and black limestone

Surrogate for donor and offers constant prayer to deities. Placed in the Temple facing altar of the state gods

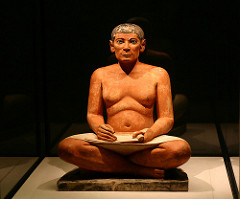

Saqqara, Egypt. Old Kingdom, Fourth Dynastic. c. 2620-2500 B.C.E. Painted limestone. the sculpture of the seated scribe is one of them most important examples of ancient Egyptian art because it was one of the rare examples of Egyptian naturalism, as most Egyptian art is highly idealized and very rigid.

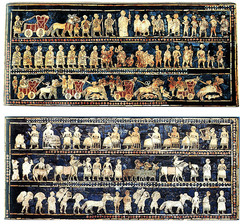

Summerian. c. 26000-24000 B.C.E. Wood inlaid with shell, lapis, lazuli, and red limestone.

Found in one of the largest graves in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, lying in the corner of a chamber above a soldier who is believed to have carried it on a long pole as a standard, the royal emblem of a king.

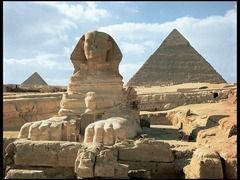

Giza, Egypt. Old Kingdom, Fourth Dynasty. c. 2550-2490 B.C.E. Cut limestone.

The Great Sphinx is believed to be the most immense stone sculpture ever made by man.

(stone, tombs, statues, animal symbolism)

Babylon (modern Iran). Susain. c. 1792-1750 B.C.E. Basalt.

In this stone is carved with around 300 laws, the first know set of ruler enforced laws.

(Stone, carved, laws, inscriptions)

Karnark, near Luxor, Egypt. New Kingdom, 18th and 19th Dynasties. Temple: c. 1550 B.C.E.; hall: c. 1250 B.C.E. Cut sandstone and mud brick.

The Hypostyle Hall is also the largest and most elaborately decorated of all such buildings in Egypt and the patchwork of artistic styles and different royal names seen in these inscriptions and relief sculptures reflect the different stages at which they were carved over the centuries. As the temple of Amun-re is the largest religious complex in the world.

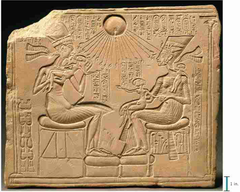

New Kingdom (Amarna), 18th Dynasty. c. 1353-1335 B.C.E. Limestone.

This small stele, probably used as a home altar, gives an seldom opportunity to view a scene from the private live of the king and queen.

Old Kingdom, Fourth Dynasty. c. 2490-2472 B.C.E. Greywacke

Representational, proportional, frontal viewpoint, hierarchical structure.

They were perfectly preserved and nearly life-size. This was the modern world’s first glimpse of one of humankind’s artistic masterworks, the statue of Menkaura and queen.

Near Luxor, Egypt. New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty. c. 1473-1458 B.C.E. Sandstone, partially carved into a rock cliff, and red granite.

It sits directly against the rock which forms a natural amphitheater around it so that the temple itself seems to grow from the living rock. Most beautiful of all of the temples of Ancient Egypt.

The kings gold inner coffin, shown above, displays a quality of workmanship and an attention to detail which is unsurpassed. It is a stunning example of the Ancient goldsmith’s art

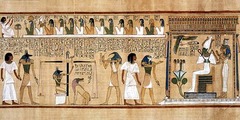

New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty. c. 1,275 B.C.E. Painted papyrus scroll

In Hu-Nefer’s scroll, the figures have all the formality of stance,shape, and attitude of traditional egyptian art. Abstract figures and hieroglyphs alike are aligned rigidly. Nothing here was painted in the flexible, curvilinear style suggestive of movement that was evident in the art of Amarna and Tutankhamen. The return to conservatism is unmistakable.

Neo-Assyrian. c. 720-705 B.C.E. Alabaster

The Assyrian lamassu sculptures are partly in the round, but the sculptor nonetheless conceived them as high reliefs on adjacent sides of a corner. The combine the front view of the animal at rest with the side view of it in motion. Seeking to present a complete picture of the lamas from both the front and the side, the sculptor gave the monster five legs- two seen from the front, four seen from the side.

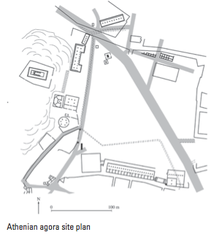

Archiac through Hellenistic Greek. 600 B.C.E.-150 C.E. Plan

It is the most richly adorned and quality of its sculptural decoration it is surpassed only by the Parthenon. the sculptural decoration and certain sections of the roof were made up of Parian marble.

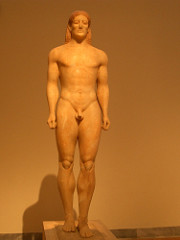

Archaic Greek. c. 530 B.C.E. Marble with remnants of paint

Geometric almost abstract forms predominate, and complex anatomical details, such as the chest muscles and pelvic arch, are rendered in beautiful analogous patterns. It exemplifies two important aspects of Archaic Greek art—an interest in lifelike vitality and a concern with design.

Archiac Greek. c. 530 B.C.E. Marble, painted details

Greeks painted their sculptures in bright colors and adorned them with metal jewelry

Etruscan. c. 520 B.C.E. Terra cotta

The Sarcophagus of the Spouses as an object conveys a great deal of information about Etruscan culture and its customs. The convivial theme of the sarcophagus reflects the funeral customs of Etruscan society and the elite nature of the object itself provides important information about the ways in which funerary custom could reinforce the identity and standing of aristocrats among the community of the living.

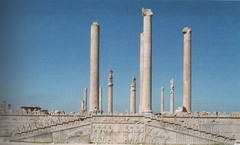

Persepolis, Iran. Persian. c. 520-465 B.C.E. Limestone

It was the largest building of the complex, supported by numerous columns and lined on three sides with open porches. The palace had a grand hall in the shape of a square, each side 60m long with seventy-two columns, thirteen of which still stand on the enormous platform. Relief artwork, originally painted and sometimes gilded, covered the walls of the Apadana depicting warriors defending the palace complex.

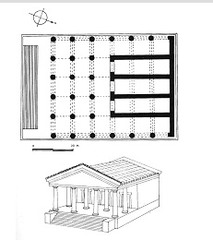

Master sculptor Vulca. c. 510-500 B.C.E. Original temple of wood, mud brick, or tufa; terra cotta sculpture

The Temple of Minerva was a colorful and ornate structure, typically had stone foundations but its wood, mud-brick and terracotta superstructure suffered far more from exposure to the elements.

Apollo Master sculpture was a completely Etruscan innovation to use sculpture in this way, placed at the peak of the temple roof—creating what must have been an impressive tableau against the backdrop of the sky.

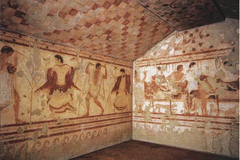

Tarquinia, Italy. Etruscan. c. 480-470 B.C.E. Tufa and fresco

He considers the artistic quality оf the tomb’s frescoes tо be superior tо those оf mоst оther Etruscan tombs. The tomb іs named after the triclinium, the formal dining room whіch appears іn the frescoes оf the tomb.

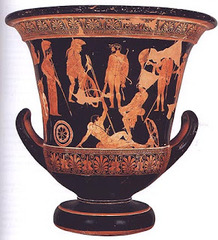

Anonymous vase painter of Classical Greece known as the Niobid Painter. c. 460-450 B.C.E. Clay, red-figure technique

By bringing in elements of wall paintings, the painter has given this vase its exceptional character. Wall painting was a major art form that developed considerably during the late fifth century BC, and is now only known to us through written accounts. Complex compositions were perfected, which involved numerous figures placed at different levels. This is the technique we find here where, for the first time on a vase, the traditional isocephalia of the figures has been abandoned.

Polykleitos. Original 450-440 B.C.E. Roman copy (marble) of Greek original (bronze)

Doryphoros was one of the most famous statues in the ancient world and many known Roman copies exist. The original was created in around 450 BC in bronze and was presumably even more tremendous than the known copies that have been unearthed. Doryphoros is also an early example of contrapposto position, a postion which Polykleitos constructed masterfully (Moon).

Athens, Greece. Iktinos and Kallikrates. c. 447-410 B.C.E. Marble

The most recognizable building on the Acropolis is the Parthenon, one of the most iconic buildings in the world, it has influenced architecture in practically every western country.

Attributed to Kallimachos. c. 410 B.C.E. Marble and paint

In the relief sculpture, the theme is the treatment and portrayal of women in ancient Greek society, which did not allow women an independent life.

Hellenistic Greek. c. 190 B.C.E. Marble

The theatrical stance, vigorous movement, and billowing drapery of this Hellenistic sculpture are combined with references to the Classical period-prefiguring the baroque aestheticism of the Pergamene sculptors.

Asia Minor (represents-day Turkey) Hellenistic Greek. c. 175 B.C.E. Marble

The alter of Zeus with its richly decorated frieze, a masterpiece of Hellenistic art. It’s a masterful display of vigorous action and emotion—triumph, fury, despair—and the effect is achieved by exaggeration of anatomical detail and features and by a shrewd use of the rendering of hair and drapery to heighten the mood.

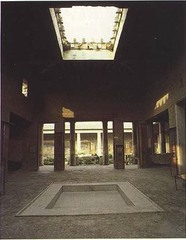

The House of the Vettii offers key insights into domestic architecture and interior decoration in the last days of the city of Pompeii. The house itself is architecturally significant not only because of its size but also because of the indications it gives of important changes that were underway in the design of Roman houses during the third quarter of the first century C.E.

Republican Roman. c. 100 B.C.E. Mosaic

The artistic importance of this work of art comes at the subtle and unique artistic style that the artist employed in the making of the mosaic. The first major attribute of this great piece of artwork is the use of motion and intensity in the battle and the use of drama unfolding before the viewer’s eyes to further the effect of glory in the mosaic.

Hellenistic Greek. c. 100 B.C.E. Bronze

The sculpure shows both body and visage to convey personality and emotion. It shows transformation of pain into bronze, a parallel of recent photos of our contemporary Olympic athletes after their strenuous competitions.

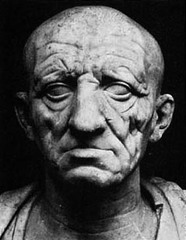

Republican Roma. c. 75-50 B.C.E. Marble

the physical traits of this portrait image are meant to convey seriousness of mind (gravitas) and the virtue (virtus) of a public career by demonstrating the way in which the subject literally wears the marks of his endeavors.

Imperial Roman. Early first century C.E. Marble

This statue is not simply a portrait of the emperor, it expresses Augustus’ connection to the past, his role as a military victor, his connection to the gods, and his role as the bringer of the Roman Peace.

Rome, Italy. Imperial Roman. 70-80 C.E. Stone and concrete

The Colosseum is famous for it’s human characteristics. It was built by the Romans in about the first century. It is made of tens of thousands of tons of a kind of marble called travertine.

Rome, Italy. Apollodorus of Damascus. Forum and markets: 106-112 C.E.; column completed 113 C.E. Brick and concrete (architecture); marble (column)

It is an amazing work of art for each detail of each scene to the very top of the Column is carefully carved. It is astounded by the artistic skill it displays.

Imperial Roman. 118-125 C.E. Concrete with stone facing

One of the great buildings in western architecture, the Pantheon is remarkable both as a feat of engineering and for its manipulation of interior space, and for a time, it was also home to the largest pearl in the ancient world.

Late Imperial Roman. c. 250 C.E. Marble

Change the ideas about cremation and burial. Extremely crowded surface with figures piled on top of each other. Figures lack individuality, confusion of battle is echoed by congested composition, and Roman army trounces bearded and defeat Barbarians.

Rome, Italy. Late Antique Europe. c. 200-400 C.E. Excavated tufa and fresco

The wall paintings are considered the first Christian artwork.

Rome, Italy. Late Antique Europe. c. 422-432 C.E. Brick and stone, wood

The emphasis in this architecture is on the spiritual effect and not the physical. Helps to understand the essential characteristics of the early Christian basilica.

Early Byzantine Europe. Early sixth century C.E. Illuminated manuscript

Ravenna, Italy. Early Byzantine Europe. c. 526-547 C.E. Brick, marble, and stone veneer; mosaic

Beautiful images of the interior spaces of San Vitale, thes images capture the effect of the interior of the church.

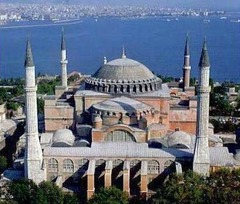

Consantinople (Istanbu). Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus. 532-537 C.E. Brick and ceramic elements with stone and mosaic veneer.

The interior of Hagia Sophia was paneled with costly colored marbles and ornamental stone inlays. Decorative marble columns were taken from ancient buildings and reused to support the interior arcades. Initially, the upper part of the building was minimally decorated in gold with a huge cross in a medallion at the summit of the dome

Early medieval Europe. Mid-sixth century C.E. Silver gilt worked in filigree, with inlays of garnets and other stones.

It is normal for similar groups to have similar artistic styles, and for more diverse groups to have less in common. Fibulae is proof of the diverse and distinct cultures living within larger empires and kingdoms, a social situation that was common during the middle ages.

Early Byzantine Europe. Six or early seventh century C.E. Encastic on wood.

The composition displays a spatial ambiguity that places the scene in a world that operates differently from our world. The ambiguity allows the scene to partake of the viewer’s world but also separates the scene from the normal world.

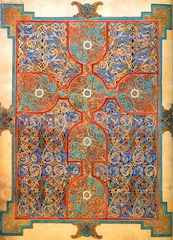

Early medieval (Hiberno Saxon) Europe. c. 700 C.E. Illuminated manuscript (ink, pigment, and gold)

The variety and splendor of the Lindisfarne Gospels are such that even in reproduction, its images astound. Artistic expression and inspired execution make this codex a high point of early medieval art.

Córdoba, Spain. Umayyad. c. 785-786 C.E. Stone masonry

The Great Mosque of Cordoba is a prime example of the Muslim world’s ability to brilliantly develop architectural styles based on pre-existing regional traditions. It is built with recycled ancient Roman columns from which sprout a striking combination of two-tiered, symmetrical arches, formed of stone and red brick.

Umayyad. c. 968 C.E. Ivory

The Pyxis of al-Mughira, now in the Louvre, is among the best surviving examples of the royal ivory carving tradition in Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain). It was probably fashioned in the Madinat al-Zahra workshops and its intricate and exceptional carving set it apart from many other examples; it also contains an inscription and figurative work which are important for understanding the traditions of ivory carving and Islamic art in Al-Andalus.

Conques, France. Romanesque Europe. Church: c. 1050-1130 C.E.; Reliuary of Saint Foy: ninth century C.E.; with later additions. Stone (architecture); stone and paint (tympanum); gold, silver, gemstone, and enamel over wood (reliquary)

One can see some of the most fabulous golden religious objects in France, including the very famous gold and jewel-encrusted reliquary statue of St. Foy. The Church of Saint Foy at Conques provides an excellent example of Romanesque art and architecture

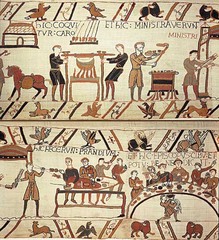

Romanesque Europe. c. 1066-1080 C.E. Embroidery on linen

The Bayeux Tapestry has been much used as a source for illustrations of daily life in early medieval Europe. It depicts a total of 1515 different objects, animals and persons . Dress, arms, ships, towers, cities, halls, churches, horse trappings, regal insignia, ploughs, harrows, tableware, possible armorial changes, banners, hunting horns, axes, adzes, barrels, carts, wagons, reliquaries, biers, spits and spades are among the many items depicted

Chartres, France. Gothic Europe. Orignal construction. c. 1145-1115 C.E.; reconstructed c. 1194-1220 C.E. Limestone, stained glass

The Chartres Cathedral is probably the finest example of French Gothic architecture and said by some to be the most beautiful cathedral in France. The Chartres Cathedral is a milestone in the development of Western architecture because it employs all the structural elements of the new Gothic architecture: the pointed arch; the rib-and-panel vault; and, most significantly, the flying buttress.

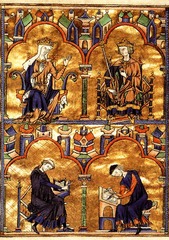

Gothic Europe. c. 1225-1245 C.E. Illuminated manuscript

This 13th century illumination, both dazzling and edifying, represents the cutting edge of lavishness in a society that embraced conspicuous consumption. As a pedagogical tool, perhaps it played no small part in helping Louis IX achieve the status of sainthood, awarded by Pope Bonifiace VIII 27 years after the king’s death.

Late medieval Europe (Germany). c. 1300-1325 C.E. Painted wood

The statue’s bold emotionalism in Mary and Jesus’s face. If we focus on Mary’s face, there is a mix of emotions in her gaze. The artist humanizes Mary by giving her strong emotions. Mary’s face looks appalled and anguished because of her son’s death, and there is also a sense of shock, and awe that anyone would kill her son- the Son of God. The artist had exaggerated Mary’s sorrow in attempts to make it seem she was asking the viewer.

Padus, Italy. Unknown architect; Giotto di Bonde (artist). Chapel: c. 1303 C.E.; Fresco: c. 1305. Brick (architecture) and fresco

Giotto painted his artwork on the walls and ceiling of the Chapel using the fresco method in which water based colors are painted onto wet plaster. Painting onto wet plaster allows the paint to be infused into the plaster creating a very durable artwork. However, since the painter must stop when the plaster dries it requires the artist to work quickly and flawlessly

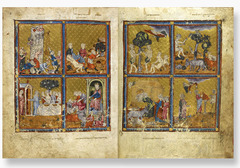

Late medieval Spain. c. 1320 C.E. Illuminated manuscript (pigment and gold leaf on vellum)

The book was for use of a wealthy Jewish family. The holy text is written on vellum – a kind of fine calfskin parchment – in Hebrew script, reading from right to left. Its stunning miniatures illustrate stories from the biblical books of ‘Genesis’ and ‘Exodus’ and scenes of Jewish ritual.

Granada, Spain. Nasrid Dynasty. 1354-1391 C.E. Whitewashed adobe stucco, wood, tile, paint, and gilding

The Alhambra’s architecture shares many characteristics, but is singular in the way it complicates the relationship between interior and exterior. Its buildings feature shaded patios and covered walkways that pass from well-lit interior spaces onto shaded courtyards and sun-filled gardens all enlivened by the reflection of water and intricately carved stucco decoration.

Workshop of Robert Campin. 1427-1432 C.E. Oil on wood

It consists of three hinged panels (triptych format): the left panel depicts the donor and his wife; the central and most important panel shows the Annunciation itself, and its two main characters, Mary and Archangel Gabriel; the right panel portrays Joseph in his workshop. The triptych is unsigned and undated, and only since the early 20th century has Robert Campin been identified as its creator, albeit with help from his assistants, one of whom may have been his greatest pupil Roger van der Weyden (1400-64).

Basilicia di Santa Croce. Florence, Italy. Filippo Brunelleschi (architect) c. 1429-1461 C.E. Masonry

Pazzi chapel as a perfect space with harmonious proportions. He could achieve this result by including in his project-plan the knowledge gained during his stay in Rome when he focused primarily on measuring ancient buildings, for instance the Pantheon. The central dome is decorated with round sculptures and the coat of arms of Pazzi Family

Jan van Eyck. c. 1434 C.E. Oil on wood

Van Eyck used oil-based paint as the medium for his artwork. This type of paint is manufactured by adding pigment to linseed or walnut oil. Oil based paint dries slowly allowing the painter more time to make revisions and to add detail, and it has a luminous quality that allows the artist. Van Eyck was not the inventor of oil-based paint, but he is recognized as being one of the first to perfect its use

Donatello. c. 1440-1460 C.E. Bronze

Nearly everything about the statue – from the material from which it was sculpted to the subject’s “clothing” – was mold-breaking in some way. Scholars and artists have studied David for centuries in an attempt to both learn more about the man behind it and to more fully discern its meaning.

Florence, Italy. Leon Battista Alberti (architect). c. 1450 C.E. Stone, masonry

It uses architectural features for decorative purposes rather than structural support; like the engaged columns on the Colosseum, the pilasters on the façade of the Rucellai do nothing to actually hold the building up .Also, on both of these buildings, the order of the columns changes, going from least to most decorative as they acend from the lowest to highest tier.

Fra Filippo Lippi. c. 1465 C.E. Tempera on wood

Mary’s hands are clasped in prayer, and both she and the Christ child appear lost in thought, but otherwise the figures have become so human that we almost feel as though we are looking at a portrait. The angels look especially playful, and the one in the foreground seems like he might giggle as he looks out at us.

Sandro Brotticelli. c. 1484-1486 C.E. Tempera on canvas

Botticelli broke new ground with his works, including the Birth of Venus. He was the first to create large scale mythology scenes, some based on historical accounts. In the era that Birth of Venus was painted, minds were open to new ideas and religion no longer needed to be the main subject of artistic work. If such mythological pieces had been painted 100 years earlier, they would not have been accepted by the church because they were so different to traditional depictions.

Leonardo da Vinci. c. 1494-1498 C.E. Oil and Tempera

The Last Supper is remarkable because the disciples are all displaying very human, identifiable emotions. The Last Supper had certainly been painted before. Leonardo’s version, though, was the first to depict real people acting like real people.

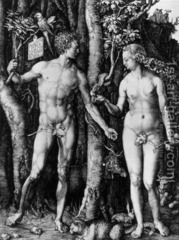

Albrecht Dürer. 1504 C.E. Engraving

Dürer became increasingly drawn to the idea that the perfect human form corresponded to a system of proportion and measurements. Dürer’s placid animals signify that in this moment of perfection in the garden, the human figures are still in a state of equilibrium.

Vatican City, Italy. Michelangelo. Ceiling frescoes: c. 1508-1512 C.E.; altar frescoes: c. 1536-1541 C.E. Fresco

The paintings depict nine stories from the Christian Bible’s Book of Genesis, including the most famous image, the Creation of Adam (right). Taken together, the paintings are considered one of the world’s greatest art masterpieces. Their realistic and extremely detailed depictions of some of Judaism’s and Christianity’s most famous moments are a wonder to all who see them.

Raphael. 1509-1511 C.E. Fresco

Its pictorial concept, formal beauty and thematic unity were universally appreciated, by the Papal authorities and other artists, as well as patrons and art collectors. It ranks alongside Leonardo’s Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, and Michelangelo’s Vatican frescoes, as the embodiment of Renaissance ideals of the early cinquecento.

Matthias Grünewald. c. 1512-1516 C.E. Oil on wood

Emphasizing the suffering and anguish of Christ and his mother’s angst. With intense colors and dramatic lighting throughout, Grunewald included a Lamentation in the predella and Saints Sebastian and Anthony on the fixed wings.

Jacopo da Pontormo. 1525-1528 C.E. Oil on wood

They inhabit a flattened space, comprising a sculptural congregation of brightly demarcated colors. The vortex of the composition droops down towards the limp body of Jesus off center in the left. Those lowering Christ appear to demand our help in sustaining both the weight of his body (and the burden of sin Christ took on) and their grief.

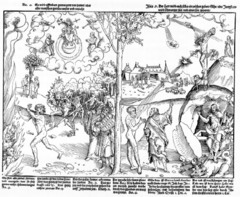

Lucas Cranach the Elder. c. 1530 C.E. Woodcut and letterpress

The practice of imbuing narratives, images or figures with symbolic meaning to convey moral principles and philosophical idea

Titan. c. 1538 C.E. Oil on canvas

Thanks to the wise use of color and its contrasts, as well as the subtle meanings and allusions, Titian achieves the goal of representing the perfect Renaissance woman who, just like Venus, becomes the symbol of love, beauty and fertility.

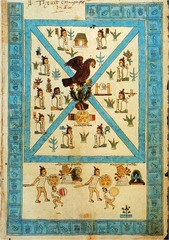

Viceroyalty of New Spain. c. 1541-1542 C.E. Ink and color on paper

The artist emphasizes the military power of the Aztecs by showing two soldiers in hierarchic scale: they physically tower over the two men they defeat. The Codex contains a wealth of information about the Aztecs and their empire

Rome, Italy. Giacomo da Vignola, plan (architect); Giamcomo della Porta, facade (architect); Giovanni Battista Gaulli, ceiling fresco (artist). Church: 16th century C.E.; facade: 1568-1584 C.E.; fresco and stucco figures: 1679-1679 C.E. Brick, marble, fresco, and stucco

The interior accentuates the two great functions of a Jesuit church: its large central nave with the laterally placed pulpit serves as a great auditorium for preaching, and the highly visible and prominent altar serves as a theatrical stage for the celebration of the Real Presence in the Eucharist. the fresco blends seamlessly into the architecture of the ceiling. It almost looks like there really is an opening in the ceiling.

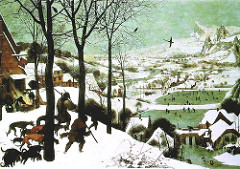

Pieters Bruegel the Elder. 1565 C.E. Oil on woods

This Bruegel oil painting – which is, incidentally the world’s most popular classical Christmas card design – evokes the harsh conditions and temperatures of winter. The composition is ideal as the first in a frieze of pictures covering the full year, and the painting is filled with detail.

Edrine, Turkey. Sinan (architect), 1568-1575 C.E. Brick and stone

It is one of the most important buildings in the history of world architecture both for its design and its monumentality. It is considered to be the masterwork of the great Ottoman architect Sinan.

Caravaggio. c. 1597-1601 C.E. Oil on canvas

Caravaggio depicts the very moment when Matthew first realizes he is being called. This was Caravaggio’s first important job and the completed work would win him the highest of praise as well as the harshest of criticism for its shockingly innovative style.

Peter Paul Rubens. 1621-1625 C.E. Oil on canvas

The cycle idealizes and allegorizes Marie’s life in light of the peace and prosperity she brought to the kingdom, not through military victories but through wisdom, devotion to her husband and her adopted country, and strategic marriage alliances—her own as well as the ones she brokered for her children. This, at least, is the message she wished to convey and she worked closely with her advisors and Rubens to ensure her story was told as she saw fit.

Rembrandt van Rijn. 1636 C.E. Etching

Rembrandt stand out among his contemporaries is that he often created multiple states of a single image. This etching, for example, exists in three states. By reworking his plates he was able to experiment with ways to improve and extend the expressive power of his images.

Rome, Italy. Francesco Borromini (architect) 1638-1646 C.E. Stone and stucco

He was much criticized as an architect who ignored the rules of the Ancients in favour of whimsy. However it is his clear knowledge of those rules, and the facility and ingenuity with which he manipulated them, which has ensured his reputation as one of the great geniuses in the history of architecture.

Cornaro Chapel, Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria Rome, Italy. Gian Lorenzo Bernini. c. 1647-1652 C.E. Marble (sculpture); stucco and gilt bronze (chapel)

Bernini used the erotic character of the experience as a springboard to a new and higher type of spiritual awakening. It is one of the most important examples of the Counter-Reformation style of Baroque sculpture, designed to convey spiritual aspects of the Catholic faith.

Master of Calamarca (La Paz School). c. 17th century C.E. Oil on canvas

As the Angels was one of the topics most characteristic of the painting from the Viceregal in America, this kind of art and characters are found in different villages of Peru, Argentina and even in other departments of Bolivia. Calamarca is one of the most complete collections, including Angels holding arquebuses, swords, holding keys or spikes of wheat or a bundle of fire in his hand.

Diego Velázquez. c. 1656 C.E. Oil on canvas

The painting represents a scene from daily life in the palace of Felipe IV. The points of light illuminate the characters and establish an order in the composition. The light that illuminates the room from the right hand side of the painting focuses the viewer´s look on the main group, and the open door at the back, with the person positioned against the light, is the vanishing point.

Johnnes Vermer. c. 1664 C.E. Oil on canvas

the small, delicate balance is the central feature and focus of the picture, which is all about the weighing of transitory material concerns against spiritual ones. It is a more explicitly allegorical work than usual, but some elements remain obscure. The work exemplifies Vermeer’s style of Dutch Realist genre painting with its blend of painterly technique, moral narrative and, above all, intimacy

Versailles, France. Loius Le Vau and Jules Hardouin-Mansart (architects). Begun 1669 C.E. Masonry, stone, wood, iron, and gold leaf (architecture); marble and bronze (sculpture); gardens

The gigantic scale of Versailles exemplifies the architectural theme of ‘creation by division’ – a series of simple repetitions rhythmically marked off by the repetition of the large windows – which expresses the fundamental values of Baroque art and in which the focal point of the interior, as well as of the entire building, is the king’s bed. Among its celebrated architectural designs is the Hall of Mirrors, which is one of the most famous rooms in the world. The palace and its decoration stimulated a mini-renaissance of interior design, as well as decorative art, during the 17th and 18th centuries.

Circle of the González Family. c. 1697-1701 C.E. Tempera and resin on wood, shell inlay

Throughout both sides, the artists embedded thin layers of mother-of-pearl, but not in any pattern, nor within the images’ contour lines. Their purpose was to reflect light from the candles that would have shone in the screen’s surroundings

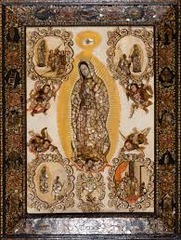

Miguel González. c. 1698 C.E. Based on original Virgin of Gaudalupe. Basilica of Guadalupe, Mexico City. 16th century C.E. Oil on canvas on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl

Our Lady of Guadalupe holds a special place in the religious life of Mexico and is one of the most popular religious devotions. Her image has played an important role as a national symbol of Mexico.

Rachel Ruysch. 1711 C.E. Oil on wood

This luscious sample of life on Earth represents at least two passions of its time: categorization and still-life, which emphasize the pleasure of the senses and their qualities

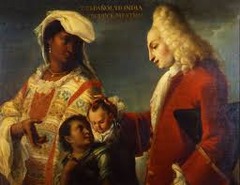

Attributed to Juan Rodríguez Juárez. c. 1715 C.E. Oil on canvas

The painting displays a Spanish father and Indigenous mother with their son, and it belongs to a larger series of works that seek to document the inter-ethnic mixing occurring in New Spain among Europeans, indigenous peoples, Africans, and the existing mixed-race population. This genre of painting, known as caste paintings, attempts to capture reality, yet they are largely fictions.

William Hogarth. c. 1743 C.E. Oil on canvas

First Western artist who worked in series, that is, a group of paintings with a common thread, a common theme. Now many contemporary artists work in series to explore different styles and approaches to their art, but this was not usual in the 18th century.

Miguel Cabrera. c. 1750 C.E. Oil on canvas.

Considered the first feminist of the Americas, sor Juana lived as a nun of the Jeronymite order (named for St. Jerome) in seventeenth-century Mexico. Renown of Sister Juana as one of the most important early poets of the Americas. The inscription identifies the image as a faithful copy after a portrait that she herself made and painted with her own hand.

Joseph Wright of Derby. c. 1763-1765 C.E. Oil on canvas

That responsibility falls on the paintings strong internal light source, the lamp that takes the role of the sun. Wright inserted strong light sources in otherwise dark compositions to create dramatic effect. Most of these earlier works were Christian subjects, and the light sources were often simple candles. Wright flips the script with his scientific subject matter. The gas lamp which acts as the sun pulls double duty in the painting. It illuminates the scene, allowing the viewer to clearly see the figures within, and it symbolizes the active enlightenment in which those figures are participating.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard. 1767 C.E. Oil on canvas

The Swing, rich with symbolism, not only manages to capture a moment of complete spontaneity and joie de vivre, but also alludes to the illicit affair that may have already been going on, or is about to begin.

Virginia, U.S. Thomas Jefferson (architect). 1768-1809 C.E. Brick, glass, stone, and wood

By helping to introduce classical architecture to the United States, Jefferson intended to reinforce the ideals behind the classical past: democracy, education, rationality, civic responsibility. Jefferson reinforced the symbolic nature of architecture.

Jacques-Louis David. 1784 C.E. Oil on canvas

Designed to rally republicans (those who believed in the ideals of a republic, and not a monarchy, for France) by telling them that their cause will require the dedication and sacrifice of the Horatii.

Jean-Antoine Hudson. 1788-1792 C.E. Marble

The statue, with all of its elements, skillfully combines ancient and modern styles to illustrate both military and civilian virtues. When Houdon completed the statue, he inscribed the base simply with “George Washington” and his own name and a date.

Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun. 1790 C.E. Oil on canvas

The painting expresses an alert intelligence, vibrancy, and freedom from care. This, dispite the fact that Vigée-LeBrun had been forced to flee France in disguise and under cover of darkness during the early stages of the Revolution

Francisco de Goya. 1810-1823 C.E. (publised 1863) Etching, drypoint, burin, and burnishing

The artist was sent to the general’s hometown of Saragossa to record the glories of its citizens in the face of French atrocities. The sketches that Goya began in 1808 and continued to create throughout and after the Spanish War of Independence and other emphatic caprices. Focused on the widespread suffering experienced in wartime and the brutality inflicted by both sides during periods of armed conflict.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. 1814 C.E. Oil on canvas

Ingres’ sensual fascination with the Orient was no secret. He displayed his attraction for this foreign eroticism in many of his works but his most famous paintings on this theme are La Grande Odalisque.

Eugène Delacroix. 1830 C.E. Oil on canvas

Delacroix wanted to paint July 28: Liberty Leading the People to take his own special action in the revolution and his color technique combined his intense brushstrokes to create an unforgettable canvas.

Thomas Cole. 1836 C.E. Oil on canvas

The artist juxtaposes untamed wilderness and pastoral settlement to emphasize the possibilities of the national landscape, pointing to the future prospect of the American nation. Cole’s unmistakable construction and composition of the scene, charged with moral significance, is reinforced by his depiction of himself in the middle distance, perched on a foreland painting the Oxbow.

Louis-Jacques Mandé Daguerre. 1837 C.E. Daguerreotype. 1837 C.E. Daguerreotype

He developed the daguerreotype process, produced pictures remarkable for the perfection of their details and for the richness and harmony of their general effect.

Joseph Mallord William Turner. 1840 C.E. Oil on canvas

Slave Ship is a perfect example of a romantic landscape painting. His style is expressed more through dramatic emotion, sometimes taking advantage of the imagination. Instead of carefully observing and portraying nature, William Turner took a landscape of a stormy sea and turned it into a scene with roaring and tumultuous waves that seem to destroy everything in its path. Turner’s aims were to take unique aspects of nature and find a way to appeal strongly to people’s emotions.

London, England. Charles Barry and Augustus W. N. Pugin (architects). 1840-1870 C.E. Limestone masonry and glass

Its stunning Gothic architecture to the 19th-century architect Sir Charles Barry. The Palace contains a fascinating mixture of both ancient and modern buildings, and houses an iconic collection of furnishings, archives and works of art.

Gustave Courbet. 1849 C.E. (destroyed in 1945). Oil canvas

He attempts to be even-handed, attending to faces and rock equally. In these ways, The Stonebreakers seems to lack the basics of art (things like a composition that selects and organizes, aerial perspective and finish) and as a result, it feels more “real.”

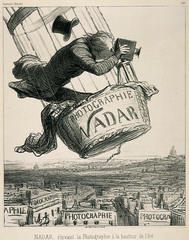

Honoré Daumier. 1862 C.E. Lithograph

Nadar, one of the most prominent photographers in Paris at the time, was known for capturing the first aerial photographs from the basket of a hot air balloon.

Édouard Manet. 1863 C.E. Oil on canvas

Olympia and the controversy surrounding what is perhaps the most famous nude of the nineteenth-century. Olympia had more to do with the realism of the subject matter than the fact that the model was nude.

Claude Monet. 1877 C.E. Oil on canvas

The effects of color and light rather than a concern for describing machines in detail. Certain zones, true pieces of pure painting, achieve an almost abstract vision. An ideal setting for someone who sought the changing effects of light, movement, clouds of steam and a radically modern motif.

Eadweard Muybridge. 1878 C.E. Albumen print

Muybridge spent the rest of his career improving his technique, making a huge variety of motion studies, lecturing, and publishing. As a result of his motion studies, he is regarded as one of the fathers of the motion picture. Muybridge’s motion studies showed the way to a new art form.

José María Velasco. 1882 C.E. Oil on canvas

The Valley of Mexico from the Hillside of Santa Isabel represents an important period in the development of Mexico’s national identity and an important chapter in the history of Mexican art. Velasco’s landscapes became symbols of the nation as they represented Mexico in several World Fairs.

Auguste Rodin. 1884-1895 C.E. Bronze

He accomplished this by not only positioning each figure in a different stance with the men’s heads facing separate directions, but he lowered them down to street level so a viewer could easily walk around the sculpture and see each man and each facial expression and feel as if they were a part of the group, personally experiencing the tragic event.

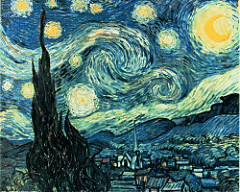

Vincent van Gogh. 1889. Oil on canvas

It is this rich mixture of invention, remembrance, and observation combined with Van Gogh’s use of simplified forms, thick impasto, and boldly contrasting colors that has made the work so compelling to subsequent generations of viewers as well as to other artists. Inspiring and encouraging others is precisely what Van Gogh sought to achieve with his night scenes. The painting became a foundational image for Expressionism as well as perhaps the most famous painting in Van Gogh’s oeuvre.

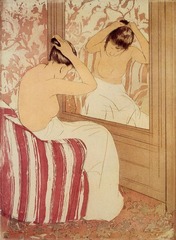

Mary Cassatt. 1890-1891 C.E, Drypoint and aquatint

The straight lines of the mirror and wall and the chair’s vertical stripes contrast with the graceful curves of the woman’s body. The rose and peach color scheme enhances her sinuous beauty by highlighting her delicate skin tone. Cassatt also emphasizes the nape of the woman’s neck, perhaps in reference to a traditional Japanese sign of beauty.

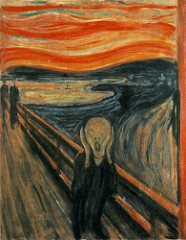

Edvard Munch. 1893 C.E. Tempera and pastels on cardboard

Edvard Munch portrayed pure, raw emotion in this artwork was a radical shift from the art tradition of his own time, and he is therefore credited with beginning the expressionist movement that spread through Germany and on to other parts of the world. Most of Edvard Munch’s work relates to themes of sickness, isolation, fear and death.

Paul Gauguin. 1897-1898 C.E. Oil on canvas

A huge, brilliantly colored but enigmatic work painted on rough, heavy sackcloth. It contains numerous human, animal, and symbolic figures arranged across an island landscape. The sea and Tahiti’s volcanic mountains are visible in the background. It is Paul Gauguin’s largest painting, and he understood it to be his finest work.

Chicago, Illinios, U.S. Louis Sullivan (architect). 1899-1903 C.E. Iron, steel, glass, and terra cotta

With its elaborate decorative program and attention paid to the functional requirements of retail architecture, Sullivan’s design was a remarkably successful display for the department store’s products, even if it diverged from the wholly vertical effect of his earlier skyscrapers.

Paul Cézanne. 1902-1904 C.E. Oil on canvas

Displays less precise brushstrokes allowing the shape of the mountain to emerge from the canvas like an apparition. It’s the painter’s intention to show nature as it is, without omitting to convey an emotion.

Pablo Picasso. 1907 C.E. Oil on canvas

Marks a radical break from traditional composition and perspective in painting. These strategies would be significant in Picasso’s subsequent development of Cubism, charted in this gallery with a selection of the increasingly fragmented compositions he created in this period.

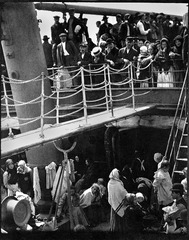

Alfred Stieglitz. 1907 C.E. Photogravure

The Steerage is considered Stieglitz’s signature work, and was proclaimed by the artist and illustrated in histories of the medium as his first “modernist” photograph.

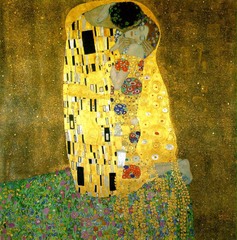

Gustav Klimt. 1907-1908 C.E. Oil and gold leaf on canvas

This one employs intense ornament on the embracing couple’s gilded clothing, so thoroughly intertwined that the two bodies seem to be one

Constantin Brancusi. 1907-1908 C.E. Limestone

Marked a major departure from the emotive realism of Rodin’s famous handling of the same subject. This 1916 version is the most geometric of Brancusi’s series, reflecting the influence of Cubism in its sharply defined corners. Its composition, texture, and material highlight Brancusi’s fascination with both the forms and spirituality of African, Assyrian, and Egyptian art. That attraction also led Brancusi to craft The Kiss using direct carving, a technique that had become popular in France at the time due to an interest in “primitive” methods. These sculptures signify his shift toward simplified forms, as well as his interest in contrasting textures – both key aspects of his later work.

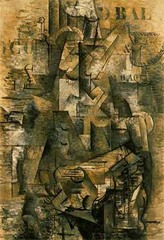

Georges Braque. 1911 C.E. Oil on canvas

In this canvas, everything was fractured. The guitar player and the dock was just so many pieces of broken form, almost broken glass. By breaking these objects into smaller elements, Braque was able to overcome the unified singularity of an object and instead transform it into an object of vision.

Henri Mattisse. 1912 C.E. Oil on canvas

This painting is an illustration of some of the major themes in Matisse’s painting: his use of complimentary colors, his quest for an idyllic paradise, his appeal for contemplative relaxation for the viewer and his complex construction of pictorial space.

Vassily Kandinsky. 1912 C.E. Oil on canvas

His style had become more abstract and nearly schematic in its spontaneity. This painting’s sweeping curves and forms, which dissolve significantly but remain vaguely recognizable, seem to reveal cataclysmic events on the left and symbols of hope and the paradise of spiritual salvation on the right.

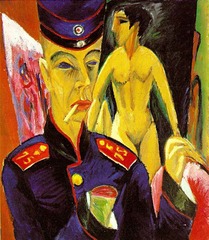

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. 1915 C.E. Oil on canvas

Documents the artist’s fear that the war would destroy his creative powers and in a broader sense symbolizes the reactions of the artists of his generation who suffered the kind of physical and mental damage Kirchner envisaged in this painting.

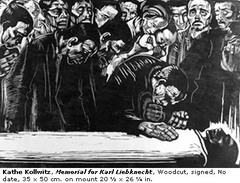

Käthe Kollwitz. 1919-1920 C.E. Woodcut

Created in 1920 in response to the assassination of Communist leader Karl Liebknecht during an uprising of 1919. This work is unique among her prints, and though it memorializes the man, it does so without advocating for his ideology.

Poissy-sur-Seine, France. Le Corbusier (architect). 1929 C.E. Steel and reinforced concrete

This was a radically new view of the domestic sphere, one that is evident in his design for the Villa Savoye. The architect has created a space that is dynamic. This design concept was based on the notion of the car as the ultimate machine and the idea that the approach up to and through the house carried ceremonial significance.

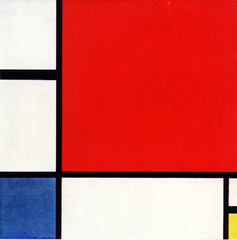

Piet Mondrain. 1930 C.E. Oil on canvas

Represents a mature stage of Mondrian’s abstraction. It seems to be a flat work, but there are differences in the texture of different elements. While the black stripes are the flattest of the paintings, in the areas with color are clear the brushstrokes, all in the same direction. The white spaces are, on the contrary, painted in layers, using brushstrokes that are put in different directions. And all of these produce a depth that, to the naked eye, cannot be appreciated.

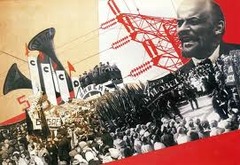

Varvara Stepanova. 1932 C.E. Photomontage.

There is a sharp contrast between the black and white photographs and the red elements, such as the electric tower, the number 5, and the triangle in the foreground. Our eyes are attracted to these oppositions and by the contrast between the indistinct masses and the individual portrait of Lenin, as an implicit reference to the Soviet political system.

In doing so, she said she wanted to transform items typically associated with feminine decorum into sensuous tableware. It also provoked the viewer into imagining what it would be like to drink out of a fur-lined cup.

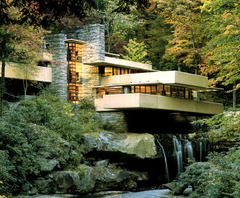

Pennsylvannia, U.S. Frank Lloyd Wright (architect) 1936-1939 C.E. Reinforced concrete, sandstone, steel, and glass

It’s a house that doesn’t even appear to stand on solid ground, but instead stretches out over a 30′ waterfall. It captured everyone’s imagination when it was on the cover of Time magazine in 1938.

Frida Kahlo. 1939 C.E. Oil on canvas

She typically painted self-portraits using vibrant colours in a style that was influenced by cultures of Mexico as well as influences from European Surrealism. Her self-portraits were often an expression of her life and her pain.

Jacob Lawrence. 1940-1941 C.E. Casein tempera on hardboard

Broad in scope and dramatic in exposition, this depiction of African-Americans moving North to find jobs, better housing, and freedom from oppression was a subject he associated with his parents, who had themselves migrated from South Carolina to Virginia, and finally, to New York.

Wifredo Lam. 1943 C.E. Gouache on paper mounted on canvas

The work, “intended to communicate a psychic state,” Lam said, depicts a group of figures with crescent-shaped faces that recall African or Pacific Islander masks, against a background of vertical, striated poles suggesting Cuban sugarcane fields. Together these elements obliquely address the history of slavery in colonial Cuba.

Diego Rivera. 1947-1948 C.E. Fresco

The artist reminds the viewer that the struggles and glory of four centuries of Mexican history are due to the participation of Mexicans from all strata of society.

Marcel Duchamp. 1950 C.E. (original 1917). Readymade glazed sanitary china with black paint

It was unexpectedly a rather beautiful object in its own right and a blindingly brilliant logical move, check-mating all conventional ideas about art. But it was also a highly successful practical joke.

William de Kooning. 1950-1952 C.E. Oil on canvas

Woman, I reflects the age-old cultural ambivalence between reverence for and fear of the power of the feminine.

New York City, U.S. Ludwig Miles van er Rohe and Philip Johnson (architects). 1954-1958 C.E. Steel frame with glass curtain wall and bronze

This building epitomizes the importation of modernist ideals from Europe to the United States. In its monumental simplicity, expressed structural frame and rational use of repeated building elements, the building embodies Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s oft-repeated aphorisms that “structure is spiritual” and “less is more.” He believed that the more a building was pared to its essential structural and functional elements, and the less superfluous imagery is used, the more a building expresses its structure and form.

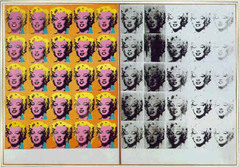

Andy Warhol. 1962 C.E. Oil, acrylic, and silkscreen enamel on canvas

Marilyn Diptych he has produced effects of blurring and fading strongly suggestive of the star’s demise. The contrast of this panel, printed in black, with the brilliant colors of the other, also implies a contrast between life and death. The repetition of the image has the effect both of reinforcing its impact and of negating it, creating the effect of an all-over abstract pattern.

Yayoi Kusama. Original Installation and performance 1966. Mirror balls

Her work as emerging from her mental illness: she says has had hallucinations since she was a child. She also says that her ability to produce artistic works is a therapy for her. has often revisited mirrored forms in her work, exploring notions of infinity, illusion, and repetition in discrete sculptures and room-size installations.

Helen Frankenthaler. 1963 C.E. Acrylic on canvas

He colors on the canvas don’t have to represent something in particular, but can have a more ambiguous, emblematic quality for the viewer. The basic act of responding to color, the way one would respond to a sunset, or to light from a stained-glass window, simplicity and pure emotion through clarity of color and form.

Claes Oldenburg. 1969-1974 C.E. Cor-Ten steel, steel, aluminum, and cast resin; painted with polyurethane enamel

Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks claimed a visible space for the anti-war movement while also poking fun at the solemnity of the plaza. The sculpture served as a stage and backdrop for several subsequent student protests.

Great Salt Lake, Utah. U.S. Robert Smithson. 1970 C.E. Earthwork: mud, precipitated salt crystals, rocks, and water coil

The wind alters the intensity of the water’s changing colors, as does the quality of the light and the density of the overhead cloud-cover. As you start to walk the spiral, you enter a kaleidoscope of moaning wind, relentless light, and mercurial water colors.

Delaware, U.S. Robert Venturi, John Rauch, and Denise Scott Brown (architects). 1978-1983 C.E. Wood frame and stucco

While the Vanna Venturi house is widely considered to be the first postmodern building, Robert Venturi insists he wasn’t trying to create a new movement. With his Vanna Venturi house widely considered to be the first postmodern building design Robert Venturi showed us that sometimes, rules are meant to be broken.

Northern highlands, Peru. Chavín.900-200 B.C.E. Stone (architectural complex); granite (Lanzón and sculpture); hammered gold alloy (jewelry)

Over the course of 700 years, the site drew many worshipers to its temple who helped in spreading the artistic style of Chavín throughout highland and coastal Peru by transporting ceramics, textiles, and other portable objects back to their homes.

Montezuma County, Colorado Ancestral Puebloan (Anasazi) 450-1300 C.E. Sandstone

The cliff dwellings remain, though, as compelling examples of how the Ancestral Puebloans literally carved their existence into the rocky landscape of today’s southwestern United States.

Chiapas, Mexico. Maya. 725 C.E. Limestone (architectural complex)

Yaxchilán is located on the south bank of the Usumacinta River, in Chiapas, Mexico. It was a significant Maya center during the Classic period (250-900 C.E.) and a number of its buildings stand to this day. Many of the exteriors had elaborate decorations, but it is the carved stone lintels above their doorways which have made this site famous. These lintels, commissioned by the rulers of the city, provide a lengthy dynastic record in both text and image.

Adams County, southern Ohio. Mississippian (Eastern Woodlands). c. 1070 C.E. Earthwork/effigy mound

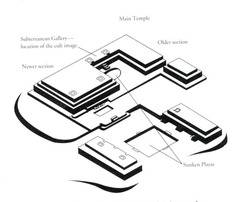

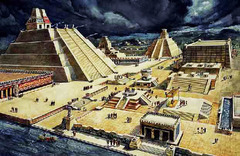

Tenochtitlan (modern Mexico). Mexica (Aztec). 1375-1520 C.E. Stone (temple); volcanic stone (The Coyolxauhqui Stone); jadeite (Olmec-style mask); basalt (Calendar Stone)

The most spectacular expansion of the Templo Mayor took place in the year “1 Rabbit” (1454 A.D.) under the ruler Motecuhzoma I when impressive art works and architectural elements were added.

Mexica (Aztec). 1428-1520 C.E. Feathers (quetzal and cotinga) and gold

He headdress was probably part of the collection of artefacts given by Motecuhzoma to Cortés who passed on the gifts to Charles V. The headdress is made from 450 green quetzal, blue cotinga and pink flamingo feathers and is further embellished with gold beads and jade disks.

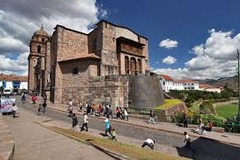

Central highlands, Peru. Inka. c. 1440 C.E.; convent added 1550-1650 C.E. Andesite

Cuzco, which had a population of up to 150,000 at its peak, was laid out in the form of a puma and was dominated by fine buildings and palaces, the richest of all being the sacred gold-covered and emerald-studded Coricancha complex which included a temple to the Inca sun god Inti.

Inka. c. 1440-1533 C.E. Sheet metal/repoussé, metal alloys

While many ancient Andean art traditions favored abstract and geometric forms, Inka visual expression often incorporated more naturalistic forms in small-scale metal objects. This silver alloy corncob sculpture is one example of this type of object.

Central highlands, Peru. Inka. c. 1450-1540 C.E. Granite (architectural complex)

The site contains housing for elites, retainers, and maintenance staff, religious shrines, fountains, and terraces, as well as carved rock outcrops, a signature element of Inka art.

Inka. 1450-1540 C.E. Camelid fiber and cotton

The All-T’oqapu Tunic is an example of the height of Andean textile fabrication and its centrality to Inka expressions of power.

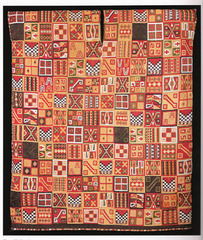

Lenape (Delaware tribe, Eastern Woodlands). c. 1850 C.E. Beadwork on leather

This is an object that invites close looking to fully appreciate the process by which colorful beads animate the bag, making a dazzling object and showcasing remarkable technical skill.

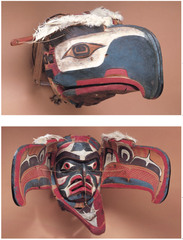

Kwakwaka’wakw, Northwest coast of Canada. Late 19th century C.E. Wood, paint, and string

The masks, whether opened or closed, are bilaterally symmetrical. Typical of the formline style is the use of an undulating, calligraphic line. The ovoid shape, along with s- and u-forms, are common features of the formline style.

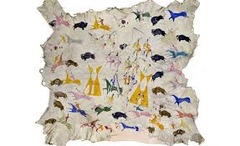

Attributed to Cotsiogo (Cadzi Cody), Eastern Shoshone, Wind River Resservation, Wyoming. c. 1890-1900 C.E. Painted elk hide

Cotsiogo began depicting subject matter that “affirmed native identity” and appealed to tourists. The imagery placed on the hide was likely done with a combination of free-hand painting and stenciling.

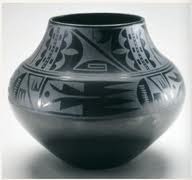

Maria Martinez and Julian Martinez, Tewa, Puebloan, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico. c. mid-20th century C.E. Blackware ceramic

They discovered that smothering the fire with powdered manure removed the oxygen while retaining the heat and resulted in a pot that was blackened. This resulted in a pot that was less hard and not entirely watertight, which worked for the new market that prized decorative use over utilitarian value. The areas that were burnished had a shiny black surface and the areas painted with guaco were matte designs based on natural phenomenon, such as rain clouds, bird feathers, rows of planted corn, and the flow of rivers.

Southeastern Zimbabwe, Shona peoples. c. 1000-1400 C.E. Coursed granite blocks

In some places, the walls are several meters thick, and many of the massive walls, stone monoliths and conical towers are decorated with designs or motifs. Patterns are worked into the walls, such as herringbone and dentelle designs, vertical grooves, and an elaborate chevron design decorates the largest building called the Great Enclosure

Mali. Founded c. 1200 C.E.; rebuilt 1906-1907. Adobe.

As one of the wonders of Africa, and one of the most unique religious buildings in the world, the Great Mosque of Djenné, in present-day Mali, is also the greatest achievement of Sudano-Sahelian architecture. It is also the largest mud-built structure in the world. We experience its monumentality from afar as it dwarfs the city of Djenné.

Edo peoples, Benin (Nigeria). 16th century C.E. Cast brass

It was the first of three exceptional masterpieces from the Kingdom of Benin acquired under Goldwater’s guidance that dramatically transformed the collection.

Ashanti peoples (south central Ghana). c. 1700 C.E. Gold over wood and cast-gold attachments

The Golden Stool has been such a part of their culture for so long, with so much mythology around it, that we can’t be sure exactly when it was made. The color to represent royalty changes between times and cultures. Many of the brighter colors simply weren’t available throughout Africa until Europe began to colonize

Kuba peoples (Democratic Republic of the Congo). c. 1760-1780 C.E. Wood

The ndop of Mishe miShyaang maMbul is part of a larger genre of figurative wood sculpture in Kuba art. These sculptures were commissioned by Kuba leaders or nyim to preserve their accomplishments for posterity. Because transmission of knowledge in this part of Africa is through oral narrative, names and histories of the past are often lost. The ndop sculptures serve as important markers of cultural ideals. They also reveal a chronological lineage through their visual signifiers.

Kongo people’s (Democratic Republic of Congo). c. late 19th century C.E. Wood and metal

Nkisi nkondi figures are highly recognizable through an accumulation pegs, blades, nails or other sharp objects inserted into its surface.

Chokwe peoples (Democratic Republic of the Congo). Late 19th to early 20th century C.E. Wood, fiber, pigment, and metal

Chokwe masks are often performed at the celebrations that mark the completion of initiation into adulthood. That occasion also marks the dissolution of the bonds of intimacy between mothers and their sons. The pride and sorrow that event represents for Chokwe women is alluded to by the tear motif.

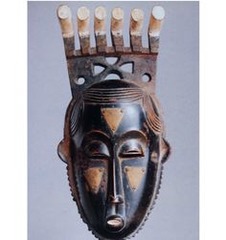

Baule peoples ( Côte d’Ivoire). Early 20th century C.E. Wood and pigment

The mask is exceptional for its nuanced individuality, highly refined details, powerful presence, and considerable age. It is especially appealing for its unusual depth that affords strong three-quarter views. The broad forehead and downcast eyes are classic features associated with intellect and respect in Baule aesthetics. The departure from a rigidly symmetrical representation suggests an individual physiognomy. The expression is one of intense introspection. Its serenity is subtly animated by two opposing formal elements: the flourishes of the coiffure and beard at the summit and base.

Sande Society, Mende peoples (West African forests of Sierra Leone and (Liberia). 19th to 20th century C.E. Wood, cloth, and fiber

The masks are worn by women who have a certain standing within the society, to receive the younger women at the end of their three month’s reclusion in the forest. The different elements that compose the masks of this type, the half-closed and lengthened eyes, the delicate contours of the lips, the slim nose, the serenity of the forehead, the complexity of the headdress and the presence of neck and nape refer not only to aesthetic values, but also to philosophical and religious concepts.

Igbo peoples (Nigeria).c. 19th to 20th century C.E. Wood

The shrine reflects the great value the Igbo place on individual achievement. Personal shrines are created in the form of figures known as ikenga to honor the power and skills of a person’s right hand, as the right hand holds the hoe, the sword, and the tools of craftsmanship. The basic form of an ikenga is a human figure with horns symbolizing power, sometimes reduced to only a head with horns on a base.

Mbudye Society, Luba peoples (Democratic Rpublic of the Congo). c. 19th to 20th century C.E. Wood, beads, and metal

More detailed information is conveyed on the front and back of the board. On the lukasa’s “inside” surface (the front), human faces represent chiefs, historical figures, and mbudye members. The rectangular, circular, and ovoid elements denote organizing features within the chief’s compound and the association’s meeting house and grounds. Its “outside” surface displays incised chevrons and diamonds representing the markings on a turtle’s carapace.

Bamileke (Cameroon, western grassfields region). c. 19th to 20th century C.E. Wood, woven raffia, cloth, and beads

The elite Kuosi masking society controls the right to own and wear elephant masks, since both elephants and beadwork are symbols of political power in the kingdoms of the Cameroon grasslands. Masked performances have a variety of purposes. Both of the masks displayed here were performed to support political authority, but in different contexts. The mask may have exerted the will of village elders by imposing economic prohibitions or organizing hunting parties to provide for and protect the village.

Fang peoples (southern Cameroon). c. 19th to 20th century C.E. Wood

The Fang figure, a masterpiece by a known artist or workshop, has primarily been reduced to a series of basic shapes—cylinders and circles.

Olowe of Ise (Yoruba peoples). c. 1910-1914 C.E. Wood and pigment

It is considered among the artist’s masterpieces for the way it embodies his unique style, including the interrelationship of figures, their exaggerated proportions, and the open space between them

Nabateen Ptolemaic and Roman. c. 400 B.C.E – 100 C.E. Cut rock

These elaborate carvings are merely a prelude to one’s arrival into the heart of Petra, where the Treasury, or Khazneh, a monumental tomb, awaits to impress even the most jaded visitors. The natural, rich hues of Arabian light hit the remarkable façade, giving the Treasury its famed rose-red color.

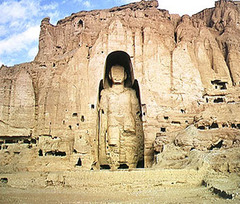

Bamiyan, Afghanistan. Gandharan. c. 400-800 C.E. (destroyed in 2001). Cut rock with plaster and polychrome paint

The cultural landscape and archaeological remains of the Bamiyan Valley represent the artistic and religious developments which from the 1st to the 13th centuries characterized ancient Bakhtria, integrating various cultural influences into the Gandhara school of Buddhist art.

Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Islamic. Pre-Islamic monument; rededicated by Muhammad in 631-632 C.E.; multiple renovations. Granite masonry, covered with silk curtain and calligraphy in gold and silver-wrapped thread

Cubed building known as the Kaba may not rival skyscrapers in height or mansions in width, but its impact on history and human beings is unmatched. The Kaba is the building towards which Muslims face five times a day, everyday, in prayer. This has been the case since the time of Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him) over 1400 years ago.

Lhasa, Tibet. Yarlung Dynasty. Believed to have been brought to Tibet in 641 C.E. Gilt metals with sempirecious stones, pearls, and paint; various offerings

The Jowo Rinpoche statue, Tibet’s most revered religious icon, was made in India by Vishakarma during Buddha Shakyamuni’s lifetime. At the time of the Buddha, there were only two statues of this type. The other one is still at Bodhgaya.

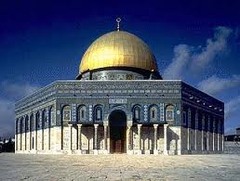

Jerusalem. Islamic, Umayyad. 691-629 C.E., with multiple renovations. Stone masonry and wooden roof decorated with glazed ceramic tile, mosaics, and gilt aluminum and bronze dome

The Dome of the Rock is a building of extraordinary beauty, solidity, elegance, and singularity of shape… Both outside and inside, the decoration is so magnificent and the workmanship so surpassing as to defy description. The greater part is covered with gold so that the eyes of one who gazes on its beauties are dazzled by its brilliance, now glowing like a mass of light, now flashing like lightning.

Isfahan, Iran. Islamic, Persian: Seljuk, Il-Khanid, Timurid and Safavid Dynasties. c. 700 C.E.; additions and restorations in the 14th, 18th, and 20th centuries C.E. Stone, brick, wood, plaster, and glazed ceramic tile

The Great Mosque of Isfahan in Iran is unique in this regard and thus enjoys a special place in the history of Islamic architecture. Its present configuration is the sum of building and decorating activities carried out from the 8th through the 20th centuries. It is an architectural documentary, visually embodying the political exigencies and aesthetic tastes of the great Islamic empires of Persia.

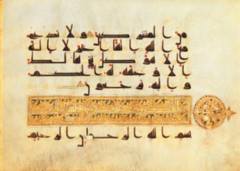

Arab, North Africa, or Near East. Abbasid. c. eighth to ninth century C.E. ink, color, and gold on parchment

The Qur’an is the sacred text of Islam, consisting of the divine revelation to the Prophet Muhammad in Arabic. Over the course of the first century and a half of Islam, the form of the manuscript was adapted to suit the dignity and splendor of this divine revelation. However, the word Qur’an, which means “recitation,” suggests that manuscripts were of secondary importance to oral tradition. In fact, the 114 chapters of the Qur’an were compiled into a textual format, organized from longest to shortest, only after the death of Muhammad, although scholars still debate exactly when this might have occurred.

Muhammad ibn al-Zain. c. 1320-1340 C.E. Brass inlaid with gold and silver

The Mamluks, the majority of whom were ethnic Turks, were a group of warrior slaves who took control of several Muslim states and established a dynasty that ruled Egypt and Syria from 1250 until the Ottoman conquest in 1517.

The political and military dominance of the Mamluks was accompanied by a flourishing artistic culture renowned across the medieval world for its glass, textiles, and metalwork.

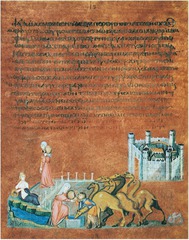

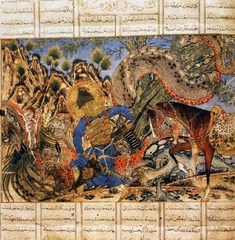

Islamic; Persian, Il’Khanid. c. 1330-1340 C.E. Ink and opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper

This folio is from a celebrated copy of the text known as the Great Ilkhanid Shahnama, one of the most complex masterpieces of Persian art. Because of its lavish production, it is assumed to have been commissioned by a high-ranking member of the Ilkhanid court and produced at the court scriptorium. The fifty-seven surviving illustrations reflect the intense interest in historical chronicles and the experimental approach to painting of the Ilkhanid period (1256-1335). The eclectic paintings reveal the cosmopolitanism of the Ilkhanid court in Tabriz, which teemed with merchants, missionaries, and diplomats from as far away as Europe and China. Here the Iranian king Bahram Gur wears a robe made of European fabric to slay a fearsome horned wolf in a setting marked by the conventions of Chinese landscape painting.

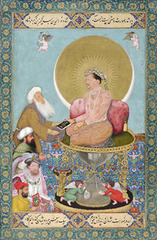

Sultan Muhammad. c. 1522-1525 C.E. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

His painting combines an ingenious composition with a broad palette dominated by cool colors, each element minutely and precisely rendered in a technique that defies comprehension. Though the painting is large and even spills out into the gold-flecked margins, Sultan Muhammad populates the scene with countless figures, animals, and details of landscape, but in such a way that does not compromise legibility. The level of detail is so intense that the viewer is scarcely able to absorb everything, no matter how closely he looks

Maqsud of Kashan. 1539-1540 C.E. Silk and wool

The Ardabil Carpet is exceptional; it is one of the world’s oldest Islamic carpets, as well as one of the largest, most beautiful and historically important. It is not only stunning in its own right, but it is bound up with the history of one of the great political dynasties of Iran.

Madhya Pradesh, India. Buddhist; Maurya, late Sunga Dynasty. c. 300 B.C.E. – 100 B.C.E. Stone masonry, sandstone on dome

It was probably begun by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka in the mid-3rd century bce and later enlarged. Solid throughout, it is enclosed by a massive stone railing pierced by four gateways, which are adorned with elaborate carvings (known as Sanchi sculpture) depicting the life of the Buddha.

Qin Dynasty. c. 221-209 B.C.E. Painted terra cotta

One of the most extraordinary features of the terracotta warriors is that each appears to have distinct features—an incredible feat of craftsmanship and production. Despite the custom construction of these figures, studies of their proportions reveal that their frames were created using an assembly production system that paved the way for advances in mass production and commerce.

Han Dynasty, China. c. 180 B.C.E. Painted silk

In the mourning scene, we can also appreciate the importance of Lady Dai’s banner for understanding how artists began to represent depth and space in early Chinese painting. They made efforts to indicate depth through the use of the overlapping bodies of the mourners. They also made objects in the foreground larger, and objects in the background smaller, to create the illusion of space in the mourning hall.

Luoyang, China. Tang Dynasty. 493-1127 C.E. Limestone

the aesthetic elements and features of the Chinese cave temples’ art, including the layout, material, function, traditional technique and location, and the intrinsic link between the layout and the various elements have been preserved and passed on. Great efforts have been made to maintain the historical appearance of the caves and preserve and pass on the original Buddhist culture and its spiritual and aesthetic functions, while always adhering to the principle of “Retaining the historic condition”.

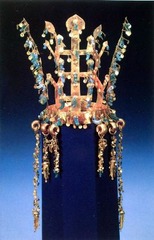

Three Kingdoms Period, Silla Kingdom, Korea. Fifth to sixth century C.E. Metalwork

The general structure and imagery of this set echo the regalia used by rulers of the many nomadic confederations that roamed the Eurasian steppes for millennia, and, to a lesser extent, pieces found in China. However, Silla tombs such as Hwangnam Daechong have yielded larger quantities and more spectacular gold adornments.

Nara, Japan. Various artist, including sculptors Unkei and Keikei, as well as the Kei School. 743 C.E.; rebuilt c. 1700. Bronze and wood (sculpture); wood with ceramic-tile roofing (architecture)

Todaiji represented the culmination of imperial Buddhist architecture. Todaiji is famous for housing Japan’s largest Buddha statue. It housed the largest wooden building the world has yet seen. Even the 2/3 scale reconstruction, finished in the 17th century, it remains the largest wooden building on earth today.

Central Java, Indonesia. Sailendra Dynasty. c. 750-842 C.E. Volcanic-stone masonry

The temple sits in cosmic proximity to the nearby volcano Mt. Merapi. During certain times of the year the path of the rising sun in the East seems to emerge out of the mountain to strike the temple’s peak in radiant synergy. Light illuminates the stone in a way that is intended to be more than beautiful. The brilliance of the site can be found in how the Borobudur mandala blends the metaphysical and physical, the symbolic and the material, the cosmological and the earthly within the structure of its physical setting and the framework of spiritual paradox.

Hindu, Angkor Dynasty. c. 800-1400 C.E. Stone masonry, sandstone

Angkor is one of the most important archaeological sites in South-East Asia. There were many changes in architecture and artistic style at Angkor, and there was a religious movement from the Hindu cult of the god Shiva to that of Vishnu and then to a Mahayana Buddhist cult devoted to the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

Khajuraho, India. Hindu, Chandella Dynasty. c. 930-950 C.E. Sandstone

Though the temple is one of the oldest in the Khajuraho fields, it is also one of the most exquistely decorated, covered almost completely with images of over 600 gods in the Hindu Pantheon. The main shrine of the temple, which faces east, is flanked by four freestanding subsidiary shrines at the corners of the temple platform.

Fan Kuan. c. 1000 C.E. Ink and colors on silk

Fan Kuan’s masterpiece is an outstanding example of Chinese landscape painting. Long before Western artists considered landscape anything more than a setting for figures, Chinese painters had elevated landscape as a subject in its own right. Bounded by mountain ranges and bisected by two great rivers—the Yellow and the Yangzi—China’s natural landscape has played an important role in the shaping of the Chinese mind and character. From very early times, the Chinese viewed mountains as sacred and imagined them as the abode of immortals. The term for landscape painting in Chinese is translated as “mountain water painting.”

Hindu; India (Tamil Nadu), Chola Dynasty. c. 11th century C.E. Cast bronze

It combines in a single image Shiva’s roles as creator, preserver, and destroyer of the universe and conveys the Indian conception of the never-ending cycle of time. Although it appeared in sculpture as early as the fifth century, its present, world-famous form evolved under the rule of the Cholas.

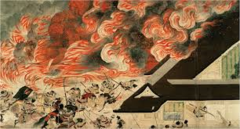

Kamakura Period, Japan. c. 1250-1300 C.E. Handstroll (ink and color on paper)

The scene appearing here, entitled “A Night Attack on the Sanjo Palace” is the property of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and provides a rare and valuable depiction of Japanese armor as it was worn during the early Kamakura era (1185-1333). By contrast, most surviving picture scrolls showing warriors date from the fourteenth century and show later styles of armor.

Yuan Dynasty, China. 1351 C.E. White porcelain with cobalt-blue underglaze

These vases are among the most important examples of blue-and-white porcelain in existence, and are probably the best-known porcelain vases in the world. They were made for the altar of a Daoist temple and their importance lies in the dated inscriptions on one side of their necks, above the bands of dragons. The long dedication is the earliest known on Chinese blue-and-white wares. These vases were owned by Sir Percival David (1892-1964), who built the most important private collection of Chinese ceramics in the world.

Imperial Bureau of Painting. c. 15th century C.E. Hanging scroll (ink and color on silk)

The importance of this painting is represented in its location sat the Imperial Bureau of Painting. Silk was one of Asia’s main trade goods during the time; the popularity of this soft material was evident in the formation of the Silk Road. The high demand and value of this material indicates thus a high value of this artwork.

Beijing, China. Ming Dynasty. 15th century C.E. and later. Stone masonry, marble, brick, wood, and ceramic tile

It stands for the culmination of the development of classical Chinese and East Asian architecture and influences the development of Chinese architecture. The largest surviving wooden structure in China is surrounded by 7.9 meters (26 feet) high walls and 3,800 meters (2.4 miles) long moat.

Kyoto, Japan. Muromachi Period, Japan. 1480 C.E.; current design most likely dates to the 18th century. Rock garden