What does Impressionism in paint ing really mean? After some forty years of agitated discussion, there exists in the public mind a confusion amount ing to bewilderment in regard to the proper answer to that question. The reason is not far to seek. Critics have been provocative and entertaining, ac cording to their fashion, with a truly journalistic contempt for any short cuts to the truth. They have played with their subject as a cat will play with a mouse to prolong the pleasurable excite ment. George Moore, for instance, pounced upon the truth when he said that “Impressionism penetrates all true painting” and only “in its most modern sense signifies the rapid noting of elusive appearance.”

Yet he allowed the thought to escape that lie might play with it upon another occasion. What is the result? Ask the average well-informed man you meet what Impressionism in painting really means, and he will reply some what as follows—“Oh—it’s a new-fan gled French way of painting everything light and airy, and of spilling all the colors of the rainbow—helter-skelter— into the same picture.” While resenting the flippancy of the gentleman’s manner, the most enthusias tic critics of the new spectral vision could hardly quarrel with the truth of this statement. When urged to a defini tion of the same subject, Camille Mau claire proceeds to industriously describe the technique of color spots invented by Claude Monet in his attempt to render the shimmer of aerial vibration. Now this method is a typical achievement of the modern mind. Suffice it here to say that, successful as it has been in pro ducing upon canvas subtle verities of light and air, it is at best a brave but crude beginning and only an experiment in the evolution of realistic painting. So engrossed is the painter with his melted outlines, his divided tones, his colored

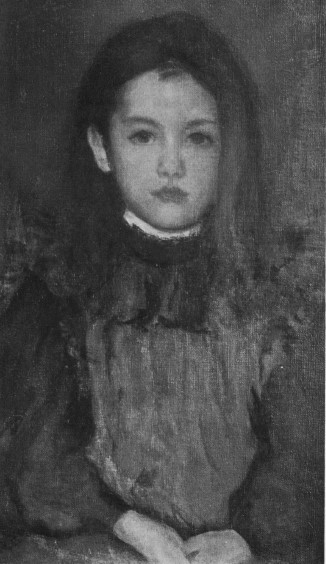

TIHE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS. BOSTON

shadows, that his picture too closely re sembles a scientific demonstration. “Colored stenography” Huneker called it. orcd stenography,” Huneker called it. It seems hardly credible that learned critics can present any one technique as the embodiment of Impressionism, and to the average mind the word seems alto- gether too big for mere technical adven- ture, however important. Yet by the common consent of painters, critics and public, Monet, Degas and the rest of that group are the Impressionists. The perplexing question is, wherein lies their right to a monopoly of the title? Opin- ions, moreover, seem to be divided whether these artists arc Impressionists because of their methods or because of their motives. Most writers agree with M. Mauclaire that the innovations of palette and brush have earned them the distinction, for these, at least, are indis putably new. Inconveniently, however, the methods of the several painters, in variably grouped together, are widely dissimilar. Some laid their paint on in gobs, others in shrill, thin washes.

If PointiUisme be Impressionism, how can Degas and the earlier Manet claim kin ship with Monet, Renoir, Sisley and Pis sarro? If, on the other hand, this little band of men are Impressionists because they have been drawn together to ex press, each in his own way, transient aspects of contemporaneous reality, how can we forget that the expression of con temporaneous reality has been the un changing purpose of true realists from the very earliest day? As for the “tran sient aspects,” the new regard for effects of life and light in passing, these things constitute one of the valuable contribu- tions of modern art. But the realistic principle dates back to Giotto. Can it be that learned critics, in cramming Im pressionism into a new, small, pigeon hole, have only thickened the fog of mis understanding that envelopes the name? It is the general belief, a belief diffi cult to wholly eradicate, that Impression ism is peculiarly modern, and that, being modern, it consists very naturally of egotistical specialisations, and adventur ous experiments in technique. Now, in the first place we forget that other times besides our own have possessed enquiring minds. It is inherent in the nature of man to be curious and experimental. He begins in the cradle by investigating the mystery of his toes, and he. ends by dabbling with Nature’s elemental forces, also with philosophy and machinery and art.

Da Vinci wrote learnedly about perspective and colored shadows, and for him, as Pater observed, “the novel im pression he conveyed, the exquisite ef fect he created counted os an end in itself—a perfect end.” What could be more “modern” in subtlety of suggestion than the Mona Lisa, with her watchful eves, her slow, disquieting smile and that fantastic background of blue-green rocks and interminable rivulets? As for Rem brandt’s soul-searching shaft of golden light, that is but another early instance of the craftsman spirit delighting in the production of “effects,” a spirit destined in our time to become so dominant and so contagious a force. But in the second place, the true Impressionism is not solely concerned with technique, nor is it the gospel of either “art for art’s sake” or “truth for truth’s sake.” In the last analysis it is the soul of the painter that counts. Here imitation, be it ever so perfect, will result in a statement of fact such os we may find in any book of ref erence. The personal and spontaneous impres sion, therefore, is requisite in realism no less than in romance. A painting may be a perfect marvel of realistic imitation —vet unworthy to be called art, because lacking the artist’s testimony of impres sion. In the Walters Collection at Baltimore we may sec side by side two small but characteristic

TIHE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM ARTS

canvases by Alma Tadema and Jean Francis Millet. The former is entitled “The Triumph of Titus.” It is a triumph of technique. The cold and lustrous sheen of the marble stairs and the variegated textures of apparel and ornament are copied in detail with un erring exactness. The imitation is as toundingly perfect. The adjacent Millet ^presents a flock of sheep, huddled by night, in their fold. They make butla shimmering blur under the misty moon. Nothing is described, nothing defined. And yet, somehow, we can see the rest less stirring of the sheep, we can feel the chill of the air, and we are deeply impressed by the poetic illusion. Now both these pictures are realistic, each in its own way. The way of Tadema was an elaborate and painstaking prose, whereas Millet’s picture is endowed with the directness and simplicity of poetic inspiration.

Tadema arrived at his knowledge of Titus and his time through toilsome years of study; Millet saw his vision of the sheep-fold one night and transcribed his impression before his brain was cool. Tadema employed the facts he found in books, Millet the se crets he learned from Nature. Tadema, the scholar, has painted with fastidious precision colorful chapters of ancient history; Millet, the poet-painter, tran scribed with spontaneous and sublime carelessness the peasants from whose midst he came, their fields and flocks, their labor and their love. Both men may be counted realists, but Millet was also an Impressionist. It is my firm belief that Impressionism is not a transient technique, but an an- cient and abiding faith, not merely the sensational production of some revolu- tionary modern painters, but one of the basic principles—I might say the one true philosophy, of all painting.

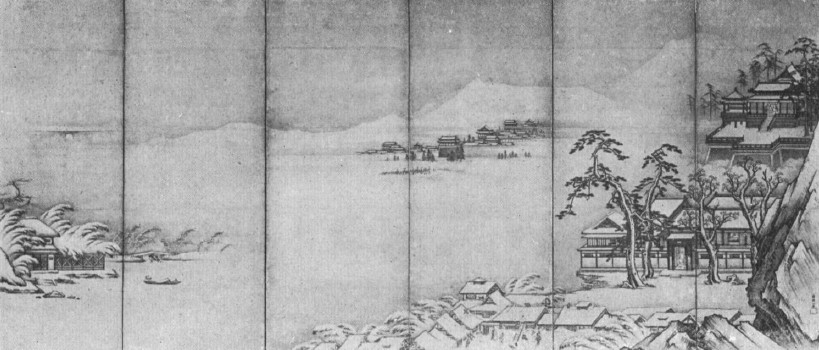

WINTER LANDSCAPE KANO SANSETSU

many as are the eyes that see, the hearts that feel, the brains that formu late their conception of visible or in tangible things, so many are life’s real Impressionists. The value of their im pressions varies according to their un derstanding. Even among those whose talents seek expression in the arts, there are all kinds of Impressionists, from the men of lofty genius on the mountain peaks of inspiration, the Michelangelos, and the Rembrandts, to the horde of petty craftsmen who labor in sterile moorlands with an unavailing and un couth endeavor. Midway upon the scale are the radical, experimental Frenchmen we have been discussing, artists who are so enamored of the appearances of ob jects under diffused or conflicting lights, so absorbed in the striving to render visual sensation, that nobility of theme seldom concerns them.

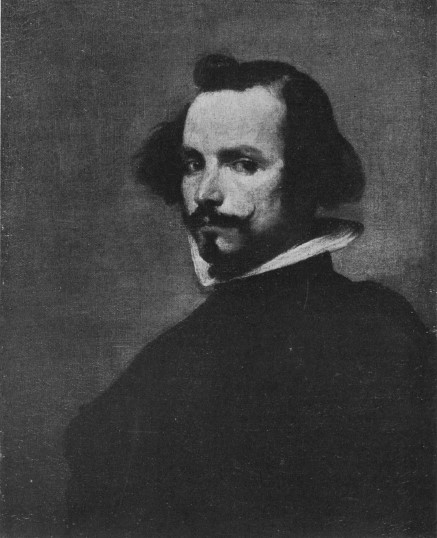

They are Im pressionists to be sure, but they repre sent merely the most recent stage in a gradual and logical development. That astute critic, R. A. M. Stevenson, was, I think, the first to point out that Impressionism in the sense which is com monly accepted to-day received its orig inal impulse from the supreme Velas quez. To him is attributed the practical demonstration of that vital principle which ordains that objects should not be painted as they are known to exist, but as they appear to the momentary and more or less abstracted gaze, under ever changing conditions of light and air. As a definition of the Impressionism of nine teenth ceritury realists, we shall see how this utters indeed the last word. How ever, if the critic had regarded Impres sionism as an eternal principle rather than as a modern practice, he would have taken for his model not merely the bril liant advances which Velasquez made upon the knowledge of his time, but the complete genius of the man, inclusive of those instincts for decoration and self expression which he inherited from his predecessors.

His Shakespearean im mensity lay in his perfect mastery of the dual nature of his art, the decorative and the representative, both interpenetrated by his own taste for color and line on the one hand, and his own vision of his model on the other. Let us, then, formulate new conclu sions, at the sacrifice, perhaps, of favor ite theories. In the first place, Impres sionism can not be said to represent any one technique nor any one way of viewing nature, but, rather, all artistic achievements, whatever the method, in which sincere, spontaneous and forth- right impressions are convincingly ex pressed through the art conceived by the brain, and the craft designed by the hand. In the second place, Impression ism is by no means solely concerned with the naturalistic portrayal of “transient aspects of contemporaneous reality.”

It is quite as high an art and a much more difficult one to give form and substance to one’s fleeting impression of intangible beauty; to sound with Whistler a chord of color; to incarnate with Watts a pow erful thought; or to perpetuate with the painters of old Japan a vanishing dream. Romance yields her impressions no less than realism. Thirdly, Impressionism is not new and strange, but marvelously old. Stevenson said that to visit Velas quez at the Prado wfas to shatter one’s faith in the modernity of modern paint ing. He might less cautiously and quite as accurately have stated that several centuries before this great Spaniard lived, far back in those dim ages of es thetic dynasties at the other end of the world, there existed in China and Japan an art of landscape painting which con tained the essence of Impressionism; that is an art in which the means of expres sion were harmoniously adapted to the artist’s original emotion.

For, after all, Impressionism is synonymous in equal measure with art itself, which is purely technical, and the artistic impulse which is, or should be, inspirational. In its only logical sense it means the giving of definite color and form to single, per sonal impressions. In this sense, then, have not all truly great painters been more or less Impressionists and should not the siirnificance of the term be widened rather than restricted?