by LIA MARKEYThis essay situates Giovanni Stradano’s engravings of the discovery of the Americas from theAmericae Retectio and Nova Reperta series within the context of their design in late sixteenthcenturyFlorence, where the artist worked at the Medici court and collaborated with the dedicateeof the prints, Luigi Alamanni. Through an analysis of the images in relation to contemporary textsabout the navigators who traveled to the Americas, as well as classical sources, emblems, and worksof art in diverse media—tapestry, print, ephemera, and fresco—the study argues that Stradano’sallegorical representations of the Americas were produced in order to make clear Florence’s rolein the invention of the New World.

INTRODUCTION

In the late 1580s, nearly a century after the travels of Columbus and Vespucci, Giovanni Stradano (also known as Jan Van der Straet and Johannes Stradanus, 1523–1605) designed engravings in two print series representing the discovery of the New World.

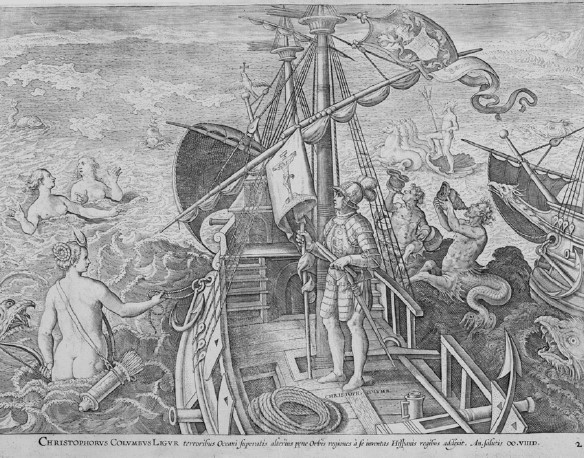

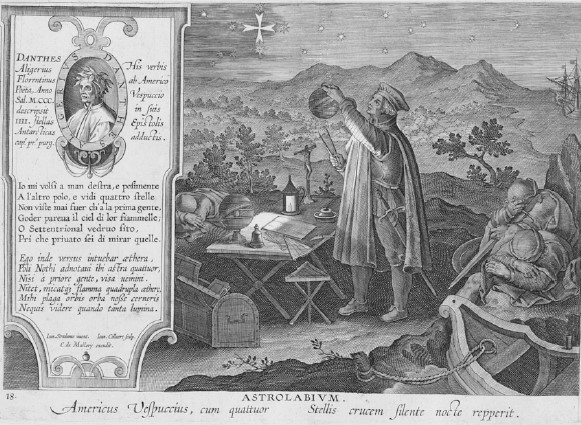

In the renowned prints navigators are fashioned as mythological heroes, and Stradano’s images suggest a fantasia, or dream, rather than a record of newsworthy events. The Americae Retectio series includes an elaborate frontispiece (fig. 1) and three prints (figs. 2–4) in chronological order that depict Christopher Columbus

Giovanni Stradano, Frontispiece for the Americae Retectio series, late1580s. Engraving. Private collection.

(1451–1506), Amerigo Vespucci (1454–1512), and Ferdinand Magellan (1480–1521). 1 Two prints from Stradano’s Nova Reperta series similarly unite allegorical imagery with captions to portray Vespucci’s encounter with the New World (figs.

5 and 6). 2 The Nova Reperta series includes nineteen prints, each representing a different invention or discovery of the recent centuries, ranging from the cure for syphilis to the production of silk. 3 Stradano’s four Americae Retectio prints and these two Nova Reperta prints possess similar iconography, and all were dedicated to members of the Alamanni family and first printed by the Galle publishing house in the late 1580s and early 1590s.

Giovanni Stradano, Columbus in the Americae Retectio series, late1580s. Engraving. Private collection.

Since the late sixteenth century, Stradano’s prints depicting the Americas have been used as artistic sources by artists and printmakers, and more recently as illustrations for scholars writing about the interaction between the Old and New Worlds. The roles of both Stradano and the Alamanni in the creation of the prints have often been disregarded, and they are frequently solely attributed to the Flemish printmaker and publisher. In the early seventeenth century, the Northern printmaking family, the De Brys, reproduced the Americae Retectio series with few alterations, and the Stradano designs are therefore often mistakenly attributed to the De Brys. 4 Since Michel de Certeau’s use of Stradano’s America image (fig. 5) from the Nova Reperta series on the frontispiece of his 1975 The Writing of History, Stradano’s prints and their reproductions by De Bry have served to illustrate

Giovanni Stradano, Vespucci in the Americae Retectio series, late 1580s.

Engraving. Private collectioncountless texts about the discovery of America and colonialism. 5 Despite the popularity of the images, and the recent fascination with promoting Stradano’s America in particular as a representation of the colonial Other, the works have not been fully considered within the context in which they were produced, and even their complex iconography remains largely unexplored. 6 Most recently, Michael Gaudio has called for a reevaluation of Stradano’s America in relation to ‘‘the very real space of the engraver’s

Giovanni Stradano, Magellan in the Americae Retectio series, late Giovanni Stradano, Magellan in the Americae Retectio series, late 1580s. Engraving. Private collection.

workshop where this print was made.

’’7 Yet this print was conceived, not in the engraver’s workshop, but rather on Stradano’s page. The prints were repositories of factual and fictional information gathered by reading, speaking, and writing about these celebrated navigators among a circumscribed group of individuals in Florence. This study argues that the America print, along with Stradano’s five other New World images, must be examined together within the context of his circle. The first part of this study therefore establishes the cultural environment of the prints’ production in late sixteenth-century Florence. Examination of Stradano’s experience as a print designer and Medici court artist, and of Luigi Alamanni’s involvement in the Florentine Accademia degli Alterati, provides critical insight into the creation of these images.

8 Stradano designed the prints around the time of Ferdinando de’ Medici’s (1549–1609) 1588 accession as Grand Duke. Previously Stradano had been involved in the creation of allegorical paintings, ephemera, and cartography

Bridgeman-Giraudon/Art Resource, NY. ” width=”623″ height=”470″ /> Giovanni Stradano, America in the Nova Reperta series, late 1580s. Engraving. Bridgeman-Giraudon/Art Resource, NY.

Bridgeman-Giraudon/Art Resource, NY. ” width=”623″ height=”470″ /> Giovanni Stradano, America in the Nova Reperta series, late 1580s. Engraving. Bridgeman-Giraudon/Art Resource, NY.

for Medici propaganda under Ferdinando’s father, Grand Duke Cosimo de’ Medici (1519–74), and his brother, Grand Duke Francesco de’ Medici (1541–87).

At the Medici court he would have encountered objects from, texts about, and images of the New World. Though the Medici were not involved in the colonization of the Americas, and they themselves were subsumed under the sovereignty of Spain, Grand Duke Ferdinando sought to strengthen cultural and economic ties with the New World during his reign. The second part of the essay closely examines the text and image of each print in relation to this milieu. Captions on the prints, chosen by the Alamanni, and Stradano’s inscriptions on the related preparatory drawings reveal specific sources for, and ideas behind, the conception of the images. 9 Using the textual materials available about the New World and stimulated both by contemporary epic literature written about the navigators and by ancient sources such as Lucretius, Stradano produced allegorical images that borrow from emblems and imprese, court frescoes, festivals, tapestries, cartography, and other printed images. These other media provided an allegorical visual language that was familiar to sixteenthcenturyviewers.

The Astrolabe in the Nova Reperta series, late 1580s. Engraving.[NC266. St81 1776St81], Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York. Giovanni Stradano, The Astrolabe in the Nova Reperta series, late1580s. Engraving. [NC266.

The Astrolabe in the Nova Reperta series, late 1580s. Engraving.[NC266. St81 1776St81], Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York. Giovanni Stradano, The Astrolabe in the Nova Reperta series, late1580s. Engraving. [NC266.

St81 1776St81], Rare Book and Manuscript Library,Columbia University in the City of New York.

media provided an allegorical visual language that was familiar to sixteenthcentury viewers. According to Jose´ Rabasa, in Stradano’s prints and especially the America engraving, ‘‘newness is produced by means of discursive arrangements of more or less readily recognized descriptive motifs. ’’10 These ‘‘descriptive motifs’’ to which Rabasa alludes are produced through the construction of complex allegorical narratives comprised of emblematic compositions that incorporate the representation of gods and navigators alongside personifications of the New World, fantastical monsters, hybrid creatures, and ancient gods. These discursive and anachronistic images would have seemed customary, and would have been comprehensible, to the prints’ late sixteenth-century audience. Yet as Sabine MacCormack has explained, there were ‘‘limits of understanding’’ in constructions of the New World, for images ‘‘did not on their own lead to a significantly new perception of Greco-Roman antiquity or of the Americas.

’’11 By framing the New World in recognizable allegorical imagery, Stradano’s engravings could declare the novel idea that the New World was a Florentine invention and patriotically revel in these discoveries. 12 In his seminal study on mythology and allegory in the Renaissance, The Survival of the Pagan Gods, Jean Seznec writes that ‘‘basically, allegory is often sheer imposture, used to reconcile the irreconcilable. ’’13 Indeed, these images do just that: theymake no reference to the Spanish, overtly connect the New World to Italy, and, with the figure of Vespucci in particular, highlight Florence’s role in the discovery. Fraught with temporal clashes between the old (pagan mythology) and the new (the discovery and invention of the Americas) the prints, disseminated throughout the world, made America part of Florence’s history, even though in reality the New World played a small role in Florence’s past and present. This claim could be made only through the language of allegory because implicit in allegory lies fantasy and the notion that the representations are imaginary.

STRADANO, ALAMANNI, AND THE ACCADEMIADEGLI ALTERATI

As is common in sixteenth-century engravings, the captions on the prints make clear that their production was the result of a collaboration between the designer or inventor (Stradano), the printmaker and publisher (Galle and Collaert), and the dedicatee or patron (the Alamanni). A Flemish artist who began working at the Medici court sometime before 1554 first as cartoon designer for Grand Duke Cosimo’s new tapestry workshop and then as an artist under Giorgio Vasari (1511–74), Stradano was by the 1560s a relatively well-known independent artist living in Florence. 14 He was an active member of the Accademia del Disegno and secured commissions for paintings and frescoes at the Medici court and also from private patrons and churches in Tuscany. Stradano was also involved in the production of several court festivals and weddings, and in the 1570s he worked briefly in Naples and in Flanders for John of Austria. 15The artist is best known for his large number of preparatory drawings for prints and tapestries that illustrate and document life at the Medici court, significant battles, hunts, as well as other current events, and religious subjects. Stradano established a partnership with the Galles, a family who ran a print publishing house in Antwerp, where most of his print designs, such as the engravings in these two series, were produced initially under Philips Galle (1537–1612).

16 The family business was subsequently taken over by Philips Galle’s son, Theodor (1571–1633), and then his grandson Johannes (1600–76). Accordingly, the first two editions of the Americae Retectio prints cite Philips Galle as the printer and Philips’s son-in-law, Adriaen Collaert (1560–1618), as the engraver, while the second edition names Johannes Galle as the printer. 17Similarly, the first edition of the Nova Reperta series labels Philips Galle as the printer of the first edition, and then Theodor and Johannes Galle are credited with the two subsequent editions. 18 A comparison between the engravings themselves and Stradano’s six finished preparatory drawings for the prints — five are in the Laurentian Library in Florence and the ‘‘America’’ print is housed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City (fig.

7) — makes clear that the Galles reproduced Stradano’s drawings with great precision and had little input into the content or style of the prints. They did, however, likely control when the prints would be published, how much they cost, and where they would be sold and distributed. Though little is known about the dissemination of the prints and though the prints are undated, a 1589 date on the Vespucci preparatory drawing in the Americae Retectio series (Laurentian Library) provides a date for Stradano’s drawings and suggests that the prints were produced soon after this time. 19 It is believed that at least four editions of the Nova Reperta series were printed between 1591 and 1638, and that the Americae Retectio series was first printed in 1589 and then reissued in 1592 for the one-hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s discovery. 20 Luigi (1558–1603) and Ludovico Alamanni are both cited as ‘‘noblemen of Florence’’ in the caption on the Americae Retectio frontispiece, but only

America, late 1580s. Pen and brown ink, brown wash, heightened with white, over black chalk. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource, NY.

Giovanni Stradano, America, late 1580s. Pen and brown ink, brown wash, heightened with white, over black chalk. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource, NY.

Luigi is named on the Nova Reperta frontispiece. 21 Gert Jan Van der Sman has pointed out that Stradano refers to Luigi Alamanni as the auctor intellectualis, or ‘‘intellectual advisor,’’ of many of his print designs in various inscriptions on preparatory drawings and sketches, and has considered Alamanni’s scholarship as a catalyst for many of Stradano’s designs. 22 Luigi Alamanni commissioned other works by Stradano, such as a series of drawings of Dante’s Divine Comedy, a series illustrating Homer’s Odyssey, and some of the prints from a series representing different types of hunting. 23 Most of the preparatory drawings for the Americae Retectio prints and the drawings for the Dante series are today located in the same archival album of the Laurentian Library in Florence, indicating that they were conserved together by the Alamanni. 24 The dates of the sheets, including the date on one of the American drawings, range from 1587 to 1589, indicating that they were produced in Florence during this two-year period of time. The album is composed of fifty-six drawings: fifty illustrate canti from the Divine Comedy, four are preparatory drawings for the Americae Retectio series, one is a preparatory drawing for the print of Vespucci and the astrolabe from the Nova Reperta series, and one is a preparatory drawing for the frontispiece for Stradano’s Calcius series — an unfinished series presumably dedicated to soccer.

25 Alamanni wrote copious notes on Dante in this album, and perhaps even did some of the drawings in it, demonstrating that he was closely involved in the creation of Stradano’s images. 26 He can also be credited with providing titles for the Dante drawings in the album, since his hand is visible on some of Stradano’s signed drawings. That the preparatory drawings for the Americae Retectio series and for the Vespucci ‘‘Astrolabe’’ print returned to Florence after they were engraved, and were placed together in the album with these important Dante drawings, demonstrates that they were considered to be important collectibles for the Alamanni. In 1587, when Alamanni and Stradano were producing the Dante drawings representing hell, Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) presented two lectures to the Accademia Fiorentina on the ‘‘Shape, Site and Size of the Inferno of Dante. ’’27 Thomas Settle proposes that the letters from Alamanni to Galileo from this period make clear that some of these illustrations in Alamanni’s album were created in conjunction with Galileo’s work, or that Galileo even had a hand in their design. 28 The drawings of the navigators also include extensive notes, in Flemish and in Stradano’s hand, to the printmakers.

Stradano wrote in the captions at the base of the drawings and added several explanatory notes in the margins in order to describe some of the iconography in the images to the printmakers. 29 Therefore, these drawings included important notes and ideas of Galileo and Stradano that Alamanni felt were worthy of safekeeping. During the time in which Stradano was producing the preparatory drawings for the prints, Luigi Alamanni was an active member of the Accademia degli Alterati, a literary group for whom the discovery of the New World was a subject of inquiry. A smaller and more private academy in comparison with other Florentine Cinquecento academies, such as the Accademia Fiorentina and the Accademia della Crusca, the Accademia degli Alterati began in 1569 among a group of Florentine noblemen who met frequently to discuss theoretical and technical issues related to their own writing and to other authors, particularly ancient poets, as well as Dante, Ariosto, and Tasso.

30 Members included individuals from prominent Florentine families, such as the Ricasoli, Neroni, Rucellai, Davanzati, and Albizzi. Two of the more famousmembers of the academy were Filippo Sassetti (1540–88), amerchant who traveled to India and whose letters from abroad are informative about India and the New World, and Giovanni Battista Strozzi (1551–1634), the author of both an epic poem about Vespucci and an elaborate Vespucci intermezzo for Prince Cosimo II de’Medici’smarriage celebration in 1608. In an undated document Strozzi wrote out a list of potential discussion topics for the Alterati: one of them included whether ‘‘the discovery of the Indies was damning or useful to our country. ’’31 According to academy member Jacopo Soldani’s funeral oration for Alamanni, Luigi suggested that a poem be written about the navigator in order ‘‘to render more glorious his country. ’’ Not coincidentally, Sassetti and Strozzi were writing about the Americas in the years just preceding Stradano’s design of these American prints for the Alamanni. Sassetti was an esteemedmember of the Academy before his travels around the world, and many of the letters that Sassetti wrote on his journey were sent to members of the group, such as Bernardo Davanzati, Pietro Vettori, Francesco Buonamici, and Strozzi.

33 Although Sassetti does not write about his brief experience in America, some of his letters refer to the discoveries of Vespucci and Columbus. 34 In December 1585, Sassetti wrote passionately to his friend Michele Saladini, a Florentine merchant living in Pisa, of Columbus’s route and discovery, and then explained: ‘‘But to return to Columbus once more, I do not think that his glory was dictated by the action of the wind . . . and I in particular know this so much so that I have helped and urged our Tender one [il Tenero] to write about it: a worthy work of such greatness and wonder as to compete with the story of Ulysses. ’’35 ‘‘Our Tender one’’ here is the Accademia degli Alterati’s pseudonym for Giovanni Battista Strozzi.

The comment that Columbus’s story rivals Ulysses’s tale is intriguing, since Alamanni was involved with Stradano in producing an illustrated edition of Homer’s epic poem that never came to fruition. This citation from Sassetti’s letter clearly shows that already by 1585 Sassetti had contacted Strozzi about writing a poem about Columbus’s heroic travels. But Strozzi chose to write about Vespucci rather than Columbus. 36 He likely began writing the poem in the mid-1580s, when he and Sassetti were obviously engaged in a discourse on the importance of writing about the Italian navigators.

37 Strozzi could have also been influenced by Giulio Cesare Stella’s (1564–1624) epic poem about Columbus, and perhaps it was knowledge of Stella’s poem that provoked Strozzi to write of Vespucci instead of Columbus. 38 In 1590, Il Colombeide (The Columbeis, 1589), Stella’s romantic text based on the writings of Gonzalo Ferna´ndez de Oviedo y Valde´s (1478–1557) and PeterMartyr d’Anghiera (1457–1526) and describing Columbus’s discovery and interaction with the natives, was sent to the Accademia degli Alterati. 39 Certainly the Academy knew of Stella’s poem earlier, since it had already been published in a pirated version in London in 1585. Similar to Stella’s poem, Strozzi’s text about Vespucci boasts of the navigator’s Florentine origins and describes him as a mythological hero. The writings of Sassetti, Stella, and Strozzi, who were all involved in the Accademia degli Alterati, reveal that Alamanni and members of the Academy were discussing the accomplishments of Vespucci as well. That Luigi Alamanni wrote and read Sassetti’s funeral oration and that the two men exchanged letters, suggests that they were not only colleagues, but close friends as well.

40 Stradano’s preparatory drawings for the prints were born out of these literary activities, which were related to the discovery of the New World as considered among the Alterati.

SOURCES AT THE MEDICI COURT

Stradano and Alamanni had other ways in which to gain information about the New World that might have provoked the production of these prints. Another Alamanni family member, Vincenzo di Andrea Alamanni (1537–91), had access to news about the Americas. From the late 1570s to the 1580s, he was an ambassador employed first by Grand Duke Francesco de’ Medici (1547–87) and then by Grand Duke Ferdinando de’ Medici to work at the Spanish court in Madrid, where he supplied information about imports from the Americas and sent updates about shipments being sent from Portugal to the Medici-controlled port at Livorno.

41It was Vincenzo Alamanni who was entrusted with the acquisition of Father Giovanni Pietro Maffei’s Historiarum indicarum (History of the Indies, 1588)—a book about the conversion and history of the natives of both the New World and Asia — on behalf of Grand Duke Ferdinando. 42 Before defining the significance of Maffei’s text for Stradano, it is necessary to expand on Grand Duke Ferdinando’s cultural politics in relation to the Americas, since Stradano’s prints evoke the interests of the duke during this first year of his dukedom. In 1588, Ferdinando left his position as cardinal in Rome to become Grand Duke of Florence, following the sudden death of his brother Francesco. In Rome he had been an avid collector of American objects, such as featherwork and hammocks: more importantly, he became the custodian of an important manuscript about Mexico, the Historia general de las cosas de Nueva Espan˜a (General History of the Things of New Spain), a codex written by the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagu´n (1499–1590). 43 This manuscript recording the history and nature of New Spain was banned by King Philip II and was likely entrusted to Ferdinando because he was cardinal protectorate of the Franciscan order and possessed an interest in the Americas. He brought these treasures to Florence and commissioned Ludovico Buti (1560–1611) to fresco American natives and a scene of the conquest of Mexico in his Armory, a space for entertaining visiting dignitaries.

Though Ferdinando and his Medici predecessors had no concrete ties to the Americas, in subsequent years he would devote himself to the development of the port of Livorno and to the creation of a colony—or at least an outpost—in the New World. 44 Ferdinando’s support of the publication of Maffei’s book on the land, people, and conversion of the New World and Asia was therefore relevant to both his political agenda and to his religious and cultural interests. The patronage of the book began during his cardinalship and the text was ultimately published in 1588 after he became Grand Duke and while Stradano was working on these print designs. Stradano refers to Maffei’s text in an inscription on the verso of the preparatory drawing for the ‘‘America’’ print (fig. 5) for the Nova Reperta series.

45 He writes with regard to one of the novel animals he portrayed in the drawing: ‘‘See volume II of the Bergomese Jesuit Pietro Maffei’s Historiarum Indicarum. ’’46 Stradano used Maffei and other contemporary textual sources about the New World when designing the iconography of the prints in his Venationes (Animal Hunt) suite of 104 engravings, also printed by the Galle family, begun as early as 1570 and initially dedicated to the Medici. 47Several of the prints in the series depict natives in feather skirts and headdresses in idyllic landscapes, where they are seen procuring birds, animals, and pearls in great abundance and using novel means. For example, the print for the ‘‘American Indians catching geese with gourds’’ (fig. 8) illustrates an unusual style of hunting that was described in great detail in Oviedo’s De la natural hystoria de las Indias (Natural History of the Indies, 1526). 48 These same Native Americans are also depicted in the scene of natives using pelicans to fish, a Chinese method of fishing with birds described in Maffei’s History.

49 Stradano also used Jose´ de Acosta’s (1539–1600) Historia natural y moral de las Indias (Natural and Moral History of the Indies, 1590) for his preparatory drawings for a never-produced print of ‘‘Indians smoking out animals. ’’50 This was another unusual means of hunting in which Mexicans set fire to land in order to force animals out of hiding and then capture them. 51 In comparison with the images of hunters in the Venationes series, Stradano’s New World representations in the Americae Retectio and the Nova Reperta appear fanciful. While many of the hunt prints are certainly imaginary, their subject matter and the series as a whole are more ethnographic in conception, endeavoring to portray realistic representations of different types of hunting throughout the world. By contrast, while perhaps also based on the writings of Maffei, Oviedo, and

Giovanni Stradano, Indians Hunting for Geese with Gourds in theVenationes series, 1580s. Engraving. [NC266. St81 1776St81], Rare Book andManuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

As a member of the Accademia del Disegno in Florence and as a participant in Vasari’s workshop at the court, Stradano would have been continually confronted with the use of emblems and imprese in art. 52 For instance, Stradano likely aided Vasari with the frescoes in the Sala degli Elementi in the Palazzo Vecchio from the late 1550s, which were commissioned by Duke Cosimo and employed imprese. 53Two of Vasari’s frescoed walls, like each of Stradano’s prints, feature a hero or god in the center of the composition acting out a narrative: Saturn is offered fruits on one wall and Venus rises from the sea (fig. 9) on the adjacent wall.

54 In the waters surrounding these figures emblematic compositions — such as a symbol of abundance with her cornucopia (at left on the Saturn wall); a turtle with a sail alluding to one of Cosimo’s favorite mottos borrowed from Augustus, festina lente (‘‘make haste slowly,’’ at right on the Saturn wall); and a triton blowing into a shell, representing fame (at right on the Venus wall)—reveal different aspects of Medici power. Francesca Fiorani has shown how these emblematic frescoes in the Palazzo Vecchio communicated Medici control over the cosmos in a similar way as the cartography produced at the court. 55 Stradano himself made maps for the private rooms in the Palazzo Vecchio and was certainly aware of the traditional use of allegory in cartography. 56He would have known well Egnazio Danti’s (1536–86) and Stefano Buonsignori’s (d. 1589) painted maps in Cosimo’s Guardaroba Nuova, a collection space comprised of cabinets decorated with different parts of the world, begun in 1563 and left unfinished in the 1580s. 57 Here the artists-cartographers incorporated fantastic and mythological creatures in their stunningly accurate portrayals of different regions.

In Stradano’s prints the visual morphology of allegory, as seen in Vasari’s frescoes and in maps produced at the Medici court, are united with knowledge about the New World acquired through circulating texts and news in order to convey a message regarding Florence’s propitious role in the Americas.

AMERICA UNVEILED

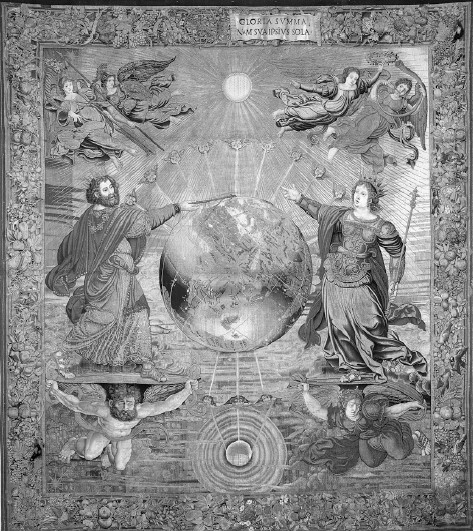

The frontispiece of Stradano’s Americae Retectio series serves to introduce this celebratory print series. It exhibits an elaborate mythology rejoicing inthe retectio, or discovery, of the Americas as an Italian endeavor.

Giorgio Vasari, Cristofano Gherardi, and workshop, Birth of Venus,1555.

Fresco. Florence, Sala degli Elementi, Palazzo Vecchio. Alinari/Art Resource,NY.the retectio, or discovery, of the Americas as an Italian endeavor. Though Magellan, a Portuguese explorer, is featured as the fourth print in this series, significantly, there is no reference to him or to his Portuguese origins on the frontispiece. In the frontispiece the gods Flora and her husband Zephyr (symbols of Florence), Janus and a pelican (a symbol for Genoa), and Oceanus (a symbol for sea travel) present a globe, while set within medallions at the top of the sheet are the two Italian navigators, Christopher Columbus and Amerigo Vespucci.

At the upper corners of the composition, other symbols for Florence and Genoa, namely, Mars and Neptune, ride chariots. Thus, Florence, Vespucci’s birthplace, is represented at left in the composition with images of Mars, Flora, and a portrait of Vespucci himself, while Genoa, Columbus’s birthplace, is represented at right with Neptune, Janus, and a portrait of Columbus. This entire scene floats above the waters off the west coast of Italy, allowing an Italocentric view of land at the bottom of the composition to highlight the cities of Florence and Genoa, again reminding the viewer of the origins of the navigators portrayed above. Stradano quite likely emulated another triumphant work of art when he designed this frontispiece.

58 The organization of the composition of the Americae Retectio frontispiece print closely resembles a tapestry from The Spheres series produced in Brussels around 1530 for John III of Portugal (1502–57) and his new Habsburg wife Catherine of Austria (1507–78). These three tapestries, each featuring a sphere held by mythological figures and attributed to the design of Bernard van Orley (1491–1542), glorify the discoveries of the Portuguese navigators during a period in which Portugal was at the height of its mercantilist power, with possessions in both Asia and Africa. 59 Jerry Brotton writes of the final tapestry in the series, representing earth held by Jupiter and Juno (fig. 10):‘‘In one breathtaking visual conceit the globe visualizes [John’s] claim to geographically distant territories, whilst also imbuing his claims with a more intangible access to esoteric cosmological power and authority reflected in the celestial iconography which surrounds the central terrestrial globe. ’’60 As a Northern tapestry designer, Stradano could have known firsthand, or heard descriptions of, these renowned textiles. While he emulates the basic composition of Van Orley’s tapestry of Jupiter and Juno, he substitutes different gods and turns the globe upright to make the New World and Europe most prominent.

In mimicking this propagandistic tapestry boasting of Portugal’s navigational and commercial prowess, Stradano usurped its message of power and glory on behalf of these two Italian navigators. Within the iconographic framework of Van Orley’s tapestry, Stradano in his print includes many more emblematic figures, as well as small details, portraits, and a map to emphasize Italy’s role in the discovery. Below the dove at the top of the print, navigational devices, namely a sextant and a compass, represent the tools the explorers used to make the journeys possible. The minuscule ships depicted on the globe represent Columbus’s and Vespucci’s voyages and are more subtle indicators of the travels of the two navigators. The frontispiece also recalls preparatory drawings for, and commemorative prints of, ephemeral events at the Medici court.

The images of the two gods aboard chariots recall the floats that were paraded down the Arno or in the Pitti Palace courtyard in Medici festivals, as well as wedding celebrations, such as the boats and seascape scenes used in the 1579 wedding between Grand Duke Francesco and Bianca Cappello (1548–87) (fig. 11), and in the

Attributed to the design of Bernard Van Orley, The Earth Protectedby Jupiter and Juno, 1530s. Tapestry.

Madrid, Palacio Real.intermezzo for the 1589 celebration for Ferdinando’s wedding. 61 For the drapery held by Flora and Janus, Stradano might have also looked to triumphal arches in public Florentine processions, where pagan gods would flank a coat-of-arms and drapery was used as decoration on arches and on the facades of churches for special events. As a court artist who worked on the production teams of various Medici festivals and public events, Stradano would have been quite familiar with this style of representation and its triumphal intent. The portraits of the two navigators within the medallions at the top of the image, combined with the blatant omission of Magellan, are perhaps the most overtly Italianist aspects of the print.

For the portrait of Vespucci, Stradano likely copied a dubious portrait of the navigator painted by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449–94) in a fresco of the Madonna della Misericordia in the family chapel in Ognissanti church in Florence (fig. 12). It is not certain whether the figure at the far left in the Ghirlandaio fresco that recalls Stradano’s portrait actually represents Amerigo Vespucci, especially since Vespucci, who in the fresco looks to be an adult, would have been an adolescent when the fresco was painted in the 1470s. But Vasari’s having written in his Le Vite delle piu` eccellenti pittori, scultori, ed architettori (The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, 1550) that the navigator was represented in the fresco, demonstrates that among sixteenth-century Florentines it was thought to be a true likeness of

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Madonna della Misericordia, 1470s. Fresco. Florence, Vespucci chapel in Ognissanti church.

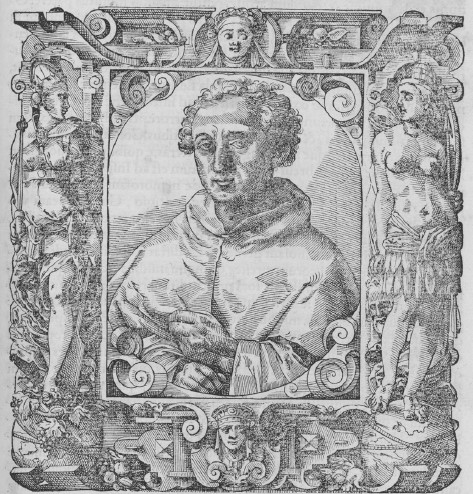

Scala/Art Resource, NY.the explorer. 62 Stradano reuses this same profile of Vespucci wearing a late fifteenth-century style hat in all of his representations of the navigator in his other prints. 63 Stradano’s portrait of Columbus was most certainly based on the portrait of the navigator first produced for Paolo Giovio’s (1483–1552) portrait museum and then reproduced both in Paolo Giovio’s Elogia virorum bellica virtute illustrium (Praise of Men Illustrious for Courage in War, 1575) (fig.

13) and in a portrait within the Medici collection. 64 This portrait type became the standard iconography for Columbus, and can be seen in many other portraits of the navigator, both painted and in print. 65 Stradano used the most well-known images of the explorers to make them easily recognizable to his viewers. With their names and origins inscribed around their likenesses, the medallions in Stradano’s print recall commemorative numismatics and endow these likenesses with antique grandeur. The spatially manipulated map of the Tuscan and Ligurian coast at the very bottom of the image makes clear that the discovery of the New World began from the northwestern coast of Italy, specifically from the navigators’ hometowns, Florence and Genoa.

Here the west coast of Italy is reoriented so that it is featured at the base of the page. Though Florence is actually a good distance from the coast, it is depicted prominently at the lower left of the map with an entire cityscape, quite close to the water’s edge and framing the view of the coast. The Medici port of Livorno is also highlighted at the left with an image of a Medici fortress. Other important port towns are labeled and illustrated similarly with recognizable buildings. Genoa marks the very center of the map and is a larger coastal town in comparison with smaller towns labeled Cogoreto, Albizola, Savona. Cogoreto and Savona are included on the map likely because Oviedo wrote that Columbus might have been from one of these towns outside of Genoa.

66 By reorienting Columbus’s and Vespucci’s birthplaces on the map, Stradano appoints these Italian cities as the starting points for the discovery of the New World. Stradano’s distorted map closely resembles Egnazio Danti’s map of Liguria in his frescoes in the Vatican (fig. 14) painted from 1580 to 1581, indicating either that the two one-time Medici court artists used the same source to depict the coast or that Stradano knew Danti’s frescoes in Rome. 67 Within Danti’s map a detail of Neptune in a chariot leading an allegory of Columbus holding a compass includes tritons, fantastical sea creatures, and

Tobias Stimmer, Columbus, in Paolo Giovio, Elogia Virorum BellicaVirtute Illustrium, Basel, 1575.

Woodcut. Print Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.a banner stating, ‘‘Christopher Columbus of Liguria: Discoverer of the New World’’ (‘‘Christophorur Columbus Ligur.

Novi Orbis Repertor’’). The use of allegory and inscription in Danti’s cartography are in the same vein as Stradano’s allegory of Genoa both in the frontispiece and in the Columbus print. Danti’s and Stradano’s maps — with their manipulated westward view of the coast of Italy, heroic representation of Columbus, and boastful Latin inscriptions — reveal the way in which cartography and allegory were used as cultural propaganda. Though Stradano is credited for the design of the image on the frontispiece, it was likely the literary scholar Alamanni who chose the

Vatican, Gallery of Maps. Scala/Art Resource, NY.

erudite Latin inscription for the caption below the image. 68 The print’s caption includes the characteristic signature of the artist and printmaker at left and the dedication to the ‘‘noble Alamanni brothers’’ at right. Both the preparatory drawing and the print include an interrogative title in the center between the artist’s signature at left and the patrons’ names at right: ‘‘QUIS POTIS EST DIGNUM POLLENT PECTORE CARMEN CONDERE PRO RERUM MAIESTATE, HISQUE REPERTIS?’’, which translates as: ‘‘Who is able to compose a song worthy of a powerful heart on behalf of the majesty of these things that have been discovered?’’These Latin words are the first lines from book 5 of Titus Lucretius Carus’s (99–55 BCE) De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things) written in the first century BCE.

By the sixteenth century the De Rerum Natura was available in several printed editions and was scrutinized within literary circles both as a significant scientific treatise and as a work of great poetry that was thought to have inspired Virgil. 69 The De Rerum Natura likely formed part of the readings and discussion of the members of the Accademia degli Alterati, who were at this time emulating the epic poetic form of Virgil. 70 Lucretius’s discussion of technology and invention could have likewise shaped Alamanni’s conception of both of Stradano’s print series, documenting the new inventions and discoveries of early modern man. The last lines of book 5 of Lucretius, in particular, describe the idea of progress in a manner that recalls the prints in the Nova Reperta series:Ships, farms, walls, laws, arms, roads, and all the rest,Rewards and pleasures, all life’s luxuries,Painting, and song, and sculpture — these were taughtSlowly, a very little at a time,By practice and by trial, as the mindWent forward searching. Time brings everythingLittle by little to the shores of lightBy grace of art and reason, till we seeAll things illuminate each other’s riseUp to the pinnacle of loftiness.

Like Lucretius, whose poem lists the various new inventions of his time, Stradano’s Nova Reperta prints each represent a different result of progress in the sixteenth century, illustrating many of the examples that Lucretius cites, including ships, arms, and painting. Lucretius’s discussion of early man is also intriguing with regard to Stradano’s prints because it corresponds with many sixteenth-century descriptions of the people of the New World:People did not know,In those days, how to work with fire, to useThe skins of animals for clothes; they livedIn groves and woods, and mountain-caves …Relying on their strength and speed, they’d huntThe forest animals by throwing rocksOr wielding clubs — there were many to bring down. The idea of the unclothed noble savage who hunts wild animals with a club is here described in Lucretius in a similar way that many sixteenth-century sources described the New World native, and like Stradano depicts the native in many of his hunt prints. For instance, Alison Brown has shown that Vespucci’s writings about the New World ‘‘were interpreted within the conceptual framework of Lucretius’’ in early sixteenth-century Florence.

73 Though written in the first century BCE, the De Rerum Natura must have appeared shockingly modern and comprehensible to these sixteenth-century scholars who were considering new inventions and discoveries, and trying to comprehend progress and this previously unknown land often equated with antiquity. Lucretius’s evocative question used in the caption — ‘‘who is able to compose a song worthy of a powerful heart on behalf of the majesty of these things that have been discovered?’’ — could have also been understood as a literal challenge to poets contemporaneously writing about the discovery. Perhaps the caption even alludes to Stella’s Columbeidos and Strozzi’s text about Vespucci’s journey. Here Stradano has not chosen to write a song, but has rather designed images ‘‘on behalf of the majesty of these things that have been discovered.’’ By referring to this other medium, the song or poem, within his own engraving, Stradano has commented on the paragone debate between the different arts, and has shown that the print is the ‘‘worthy’’ medium for depicting this ‘‘majesty.’’ The following three prints in the series thus represent visual printed songs dedicated to each discoverer.