A pilgrimage to the newly dedicated church of St. Gregory the Great, which is somewhat remotely situated at Brooklyn Avenue and t. John’s Place, Brooklyn, N. Y., is recompensed by the unexpected sight of a beautiful basilica of urest Roman type whose interior decoration is carried out in fresco buono that ancient and noble ural process, all but lost to-day, which, as em ployed by the Renaissance ‘masters Michelangelo, Rafaello, Luini and others, produced some of the most splendid results known to the annals of art. he architects of St. Gregory’s, Messrs. Helmle and Corbett of New York, have taken for models he two oldest existing basilicas in Rome those of San Clemente and of Santa Maria in Trastevere, upposed to date from the fifth century.

They have not so much copied literally as embodied the spiritf these typical early Christian churches, includihg the graceful campanile and adding to the main ody of the structure all the familiar appurtenances of a complete Catholic church in modern times. ut the crowning glory of St. Gregory’s is its in- terior decoration in true antique fresco by Maximilian F. Friederang, of whom more anon. It is an architectural principle generally conceded hat no church can be considered complete or thor oughly successful which is not decorated through- ut in color. This is especially true of a Roman Catholic church of the basilica type, which also as more unbroken wall space than any other and consequently offers better opportunity for large esign and figure composition. In the pre-Roman- esque churches like those of San Apollinare and San Vitale at Ravenna such opportunities were utilizedmainly

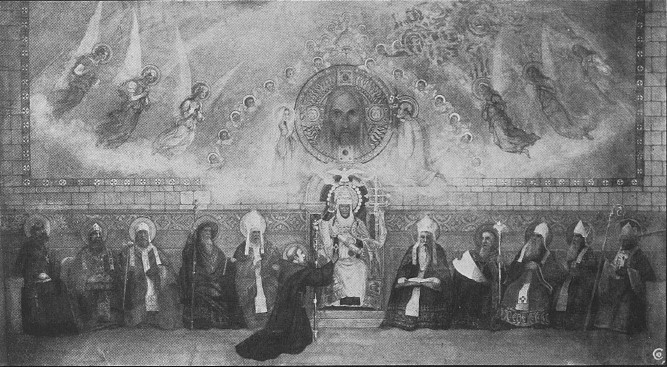

STIUDY FORl THE MAIN DECORATIONS

in mosaics. Even in the sixteenth century, after Michelangelo and Rafaello had rediscovered the art and craftsmanship of true fresco (tradition says they achieved it by minute analysis of mate rials used by the ancient fresco painters) the mhral work of St. Peter’s and the Vatican was controlled by a league of conventional decorators who per sistently opposed the large, austere method of Michelangelo. He was not, in fact, a painter, but essentially a sculptor and architect. For that very reason he held out for fresco buono as the only true architectural painting, because pictures prop erly executed in that medium become an integral part of the building they beautify, their mineral colors crystallizing into an unalterable marble-like surface as permanent as the adamantine wall itself. So Michelangelo was “sidetracked” as we say to the obscure, bare and rectangular Sistine Chapel where alone and in proud secrecy he produced those titanic records which are the unfading and unmatched wonder of the world to this day. With his passing the art swiftly fell from its zenith into desuetude and decay. No frescoes worthy of the name have come down to us unimpaired in the last three hundred years unless we except the work of Puvis de Chavannes, which technically is not fresco at all, but only painted canvas shipped across the seas (in the case of the Boston Public Library) to be fixed upon the walls of a building which the artist had never seen.

True, these panels by Puvis are a magnificent success in their way and their success is precisely that of the degree in which their color, texture, surface and whole general«c ture has been forced by a unique genius of artisteraft.Smanship to approximately imitate genuine fresco. As for the so-called “mural paintings” of our contemporary Kenyon Coxes, Blashfields and Max Boh ms, and of all their school with due defer ence to these worthy and capable artiststhey arc simply magnified easel-pictures, or the good old traditional studio oil-paintings, adapted to their destined walls by their measurements alone. Enter St. Gregory’s from the columned portico, which is a modern version of the classic atrium, and you come directly into the nave. Somehow you have been transported in the twinkling of an eye from Long Island to Italy. From the clerestory windows aloft, the light fills the vault of the tim- bered roof, descending softly upon the tinted walls and two rows of stately columns of warm purplish Connecticut granite, which, by every architectural device of line, color and illumination, lead up to the glorified apse and semidomed sanctuary, in which is set a baldachino altar of exquisitely wrought Car rara marble inlaid with rich mosaic medallions.

The principal frescorepresenting St. Gregory surrounded by the Fathers of the Greek and Latin churches, despatching St. Augustine of Canterbury on the mission to Britain which was to convert the Saxon King Ethelbert to Christianityfills the domed space of the sanctuary, above which is fig ured Christ triumphant: while below, the walls of the apse are covered with rich and intricate orna mental designs of symbolical nature. The brightest of pure colors arc used hereblue, orange and red, but they are so craftily balanced, broken and inter spersed that the whole fuses into a mellow golden mist, a magical effect that is enhanced by the light ing from little windows in the roof. And all the time the modeling and detail of the figures in the pictures are perfectly distinct, due to the peculiar pigments and surface of the fresco, luminous with out glitter and smooth without being hard or un duly flat. On a sunny day this light changes with every passing cloud in the sky, from celestial radi ance to mystic shadow, as though the imaged walls were imbued with sentient life and emotion.In this work of true fresco in its right architectural

MAIN DECORATIO’N IN PLACE, ‘VAULT OF APSE

accord Maximilian Friederang sees the cul mination of a lifetime’s courageous ambition and self-sacrificing toil. He is a character unique in our time a sort of belated medieval. combining the attributes of artist and artisan, chemist and colorist, scholar and religious zealot. German born, he spent the years of his youth studying in Rome, and then came to America, where the whole of his professional life of over a quarter of a century has been spent. Ilis work in various churches and public buildings has been known all along to the leading architects, from Stanford White to Cass Gilbert. But it was not until he completed his marvelous frescoes in the Byzantine dome of the Church of St. Joseph at Babylon, L. I., that he came into prominent notice as the one man capable of leading the modern revival of fresco buono and placing its great decorative possibilities on a solid foundation. This high estimate is more than confirmed by the enthusiastic praises that critics of authority who have visited St. Gregory’s thus far have bestowed. If any mistake has been made, it is in the placing the baUlachino where it is. It is certainly too large for the frescoes because it competes with them and shuts off the view for those seated in the front rows of seats. A beautiful altar fiat against the wall might have been better.