Titian (1477-1576) is the last of the quartet of the world’s painters; and as a painter pure and simple, in the matter of presenting nature, in his mastery of color, in his sure, strong brushwork, in his ability to keep a composition a unit, in fact, in all those things that go to make a purely pictorial effect, he probably stands at the head of them all. It is the dignity and grandeur of human existence that Titian presents to us. In Correggio was the life and joy and vivacity of nature; in Titian the grand, the magnificent, the sublimely sensuous. He builds «p masses and spaces and forms in his pictures that have the grandeur and power of nlountain ranges.

Titian does not appeal directly to our reasoning powers any more than does the vibrating blue of sky, or a smiling meadow, or a glorious sunset, or towering mountain range; but he makes us feel the grand and sublime in nature, and reaches our intellect through our feelings. Everything Titian touches with his magic brush glows with wonderful hues, and takes on an exalted mood. His choice of subjects was wide— the religious, historical, mythological and allegorical were all treated by him. Landscape he treated with consummate grandeur, and his influence in this respect lived on in Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorraine. In portraiture he was perhaps the greatest painter that ever lived. Titian was born in the Valley of Cadore, a place full of grandeur in mountain and forest: and the impress of nature around him during his youth—and in repeated visits —is seen in all his succeeding work. There is a story of this early youth of Titian which characterizes the trend of his whole life in art. It is said that, whereas other painters began in early youth by drawing in charcoal or on a slate, he pressed the juices out of certain flowers and painted with them.

Thus early did he indicate his position as the greatest colorist the wurld has ever seen. Titian began his studies in art at the age of ten, when he was placed under Zuccato, a painter and worker in mosaics; but later he became a fellow pupil of Giorgione under Giovanni Bellini. Titian’s earliest work shows Bellini’s influence in his mode of composition, but he became still more influenced by Giorgione. When Titian and Giorgione were youths of about eighteen or nineteen they worked together on the frescoes of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi; but a preference shown for Titian’s work caused an estrangement between the two friends. For several years after, however, the influence of Giorgione on the mind and style of Titian was so great that it is hard to tell their work apart, and on the early death of Giorgione, Titian was commissioned to complete his unfinished pictures. But Titian’s style was not long in forming itself, and he was famous before the age of thirty.

From middle life on Titian lived in princely style, surrounded by friends— philosophers and poets—; and honors and commissions flowed to him from all sides. He was considered the greatest portrait painter living, and there was not a prince or potentate, a poet or beauty, who did not wish to have him paint his or her portrait Titian loved pleasure, and has often been reproached for his intimacy with the “witty profligate Pietro Aretino”; but he never flagged in his industry, and his powers were undimmed at an age when most men would be too feeble for any effort. Titian has often been accused of lack in drawing; but no one seeing his Sacred and Profane Love, in the Borghese Gallery, would agree with the fault-finders. (See the cut, p. 67.) The nude figure in that picture is most exquisite in pose and line and modeling.

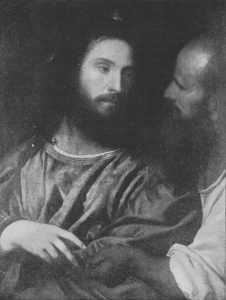

TRIBUTE MONEY. TITIAN

It is a marvelous feat of rendering modeling in full light. Full light as well as full shadow obliterates modeling to a great extent, and roundness and form are felt more than actually seen. But in this figure the modeling is as truly given as though it had been marked by the strongest contrast of light and shade. What a beautiful glow of flesh too, and what softness of texture! It is beautiful, too, in its decorative element, this picture. The masses of dark foliage and light draperies and the flesh of figures are most happily placed. There is a richness and depth and glow altogether charming, and there is besides the grand feeling so characteristic of Titian. To be sure, Titian’s drawing becomes looser in later life, but then he draws more by mass than by line.

During DUrer’s visit to Venice, it was perhaps inevitable that comparisons should be made between his work and Titian’s. Italy had gone wild over DUrer, who in technique was the opposite of Titian. DUrer carried detail to excess, and spent as much time over a curl of hair as over any other part of a picture. Titian painted in broad masses. It was in a way to show that he could paint detail if he chose that Titian painted tne famous Christ and the Tribute Money, now in the Dresden Gallery. But what a difference in result! Although everything is painted with the most minute care, everything counts in mass. What a careful rendering of dome of head, of soft wrinkled flesh, of brown sinewy hand in the Pharisee! And then the fairness of skin in the Christ-face, the delicacy of line and the softness of modeling! The hair lies so lightly and easily on the head that one might any moment expect it to move.

The management of values is superb as they range over the fair form of Christ to the dark one of the Pharisee. What a strong rendering of character too in the geutle but penetrating glance of Christ and the crafty expression of the hardened Pharisee! Then, although every inch of the picture is well painted and full of interest, how well the attention is centered on the expressive head of Christ! “This wonderful work is expressive in every detail; the action of the hands supplies the place of words.” In his religious pictures in general Titian does not show that spirituality which marks the works of some painters of the Renaissance, Francia’s for instance. Still they are marked by a nobility, a grandeur and dignity that make them truly impressive. In the Dresden Gallery, the Virgin, Child and Saints is a magnificent example of grandeur or form and mass. Another religious picture of grandeur in composition is the Madonna with Several Saints and the Pesaro Family as Donors, in the S. Maria dei Frari at Venice. Perhaps the best known of his religious pictures are the Presentation of the Virgin, in the Academy at Venice; the Entombment, in the Louvre; and the Assumption of the Virgin, in the Academy of Venice.

Of the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple (see the cut, p. 39), Kugler says: “This great picture is of a cheerful, worldly character. A crowd of figures, among whom are the senators and procurators of St. Mark’s, are looking on in astonishment and excitement while the lovely child, holding its little blue garment daintily in its right hand, is ascending the steps of the Temple, where the astonished high priest, attended by a Levite, is receiving her with a benediction. The scene is rendered with great naïveté, and with an incomparable glow of color.” One cannot help feeling in the picture, however, that the subject is belittled by the surroundings. The stone steps, for instance, are too uninteresting to occupy so large a space in the composition, and the little figure of the Virgin is almost lost in the splendor of the architecture behind her and the massiveness of the steps upon which she stands.

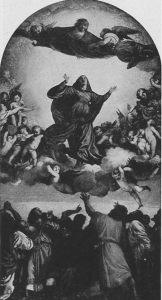

The Entombment, however, is one of the most complete and perfect pictorial compositions in the world. In the perfect disposition and balance of line and masses; in the beauty of light and shade and color and atmosphere; in the rendering of texture and the modeling; in fact, in all those things which go to make a perfect pictorial effect, this picture is superb. Then, above all, the scene is rendered with such sure dramatic instinct—there is nothing theatrical or forced about it, all is so truly dignified and noble in its strong emotion and action—that one need not wonder that this picture greatly influenced succeeding arL It is surely one of Titian’s greatest efforts. The Assumption has been placed as one of the twelve pictures of the world, and it deservedly holds a high rank. The noble, beautifully powerful figure of the Virgin, as it is impelled upward surrounded by angels, the agitated group of disciples and apostles beneath, the swimming glorious light in which the All Father soars, and the beauty and grace of the glorifying angels are all given with incomparable power.

ASSUMPTION OF THE VIRGIN. TITIAN

Titian’s portraits are wonderful in close characterization of personality. The cunning fox-like face and bent form of his portrait of Pope Paul III. is an instance. Where his subjects will allow, he endows them with a courtly dignity and high breeding, as for instance his Catherine Cornaro, in the Uffizi, and the famous Donna Bella, in the Pitti Gallery. These show a wonderful rendering of textures and management of light and shade, and they look out at us from the canvas with a stately, dignified life.

The Young Man with the Glove, in the Louvre, is remarkable for depth of feeling and an intensely felt personality. Titian also painted allegorical figures which appear to have been portraits. The well-known Flora, in the Uffizi, is an example of this. It is a wonderful rendering of soft, living flesh and rounded form, of shining curls of hair and rich drapery; and there is a depth and dignity about it altogether charming. Titian painted several pictures of Emperor Charles V. It was while painting one of these portraits at Augsburg that the incident occurred which has been so often related. Titian was then seventy years old. He is said to have dropped his brush, whereupon Charles picked it up and presented it to the painter, who made many excuses; but Charles replied that “Titian was worthy of being served by Caesar.’’

When at Augsburg, Titian was ennobled and created a count of the empire, with a pension of two hundred gold ducats. Titian’s powers did not seem to dim even in very old age. He was eighty-one when he painted the Martyrdom of St. Lawrence, one of his largest and grandest compositions. He lived to be ninety-nine years old, and it was only in his nineties that he showed any sign of declining power, and as Mrs. Jameson says: “And then it seemed as if sorrow rather than time had reached him and conquered him at last. He had lost his daughter Lavina, who had been his model for many beautiful pictures.

The death of many friends, the companions of his convivial hours, left him ’alone in his glory,’ and he found in his beloved art the only refuge from grief. His son Pomponio was still the same worthless profligate in age that he had been in youth; his son Orazio attended upon him with truly filial duty and affection, and under his father’s tuition became an accomplished artist; . . . The early morning and the evening hour found him at his easel; or lingering in his little garden (where he had feasted with Aretino and Sansovino, and Bembo and Ariosto, and ‘the most gracious Virginia’ and ‘the most beautiful Violante’), and gazing on the setting sun, with a thought perhaps of his own long and bright career fast hastening to its close; not that such antici- pations clouded his cheerful spirit—buoyant to the last!”

ENTOMBMENT OF CHRIST. TITIAN.

In 1575 the plague struck Venice, and in 1576 the great master was stricken with it and died. The sanitary laws forbade burial in churches during the plague, but the Venetian veneration for the grand master was so great that these were set aside, and his remains were borne to the tomb with great honors and deposited in the church of S. Maria dei Frari, for which he had painted his famous Assumption.