CREATION OF MAN. MICHELANGELO

Florentine and Roman Schools: Da Vinci

The art of a nation passes through very much the same development as that of an individual. There are the first crude efforts, and then the struggle with technical difficulties. The delirious pleasure of over coming the latter, then, very often makes one forget the end for the means, and one falls in love with the language itself rather than with the things to be expressed. Ever increasing power of observation and per ception also captivates, and the result is often mere transcription from nature. There is, however, in this stage a certain naive unconsciousness, a simplicity of thought, which is often lost in the maturity of effort. It is this unconscious, naive, sensitive quality about the Early Renais sance work that makes it so attractive. But technique in all its branches had now been mastered?one process by one school or indi vidual, another process by another school or individual. Perspective, both linear and aerial, line, light and shade, color and com position, no more offered any difficulties.

One school had developed in grandeur and simplicity, another in sentiment, another in ideal quality, and so on. Now the giants of painting came, and united all these excel lencies of quality and technical accomplish ments into one great, perfect art. Thus we have the period of the High Renaissance. The introduction of oils had been the highest technical triumph of the Early Renaissance, and by its aid the range of painting was widened immeasurably. The art of painting was to blossom into greater glory than ever before in the history of the world; for perfect technique, beauty of line, form, color, light and shade, were combined with depth of feeling and lofty thought.

Leonardo Da Vinci

The first master mind in point of time of this new era was Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519). He was one of those rare beings upon whom nature seems to shower every gift in her power. Science, music, poetry, painting, sculpture, architecture were all within his power, and he excelled in them all. It is no wonder that he has been called “the Miracle of that miraculous age, the Renaissance,” the wiz ard, magician, dreamer, the scentist, realist and idealist by different writers. So uni versal a genius probably never lived before. His knowledge was simply astonishing for his time. Manuscripts left by him have proven that he anticipated discoveries in science long before the times were ripe for their acceptance. He was the greatest mathematician, and the most ingenious mechanic of his time; and as chemist and engineer, he stood in the front rank. When we add to this an imposing but still mag netic and winning personality, endowed with a physique so strong that he could easily bend a horseshoe with his bare hands, and with a body tall, straight and graceful and crowned by a head noble and beautiful in shape, we need not wonder that Vasari said of him: “He was perfection in all things.” His very versatility, his love of experimen tation and discovery, proved the cause of an immeasurable loss to art. His energies were directed in so many channels that little time was left for painting; and his passion for experimenting caused him to use new oils, varnishes, and colors, that proved dis astrous to his own work, but of great value to his successors.

There are few works left by Leonardo da Vinci, and some of his grand conceptions can be but feebly guessed at from his sketches. He has been classed variously with the Florentine and Milanese School. Though he was Florentine by training, his greatest influence was felt at Milan; but he was so universal a genius that it is hard to class him anywhere. His greatest gift to art was the discovery of the poetry of mystery in light and shade and the rendering of subtility of personality, ?of soul. Light and shade with him reaches its highest perfection, and perhaps no other man has been able so well to express the inner spirit through the outward form. ” He had mastered the whole scale of human ex pression from the sublime and heavenly pure to the depths of absurdity and corruption.,, This study of expression was a passion with him. He always carried a sketch-book, and would sometimes follow people of striking peculiarity a whole day, then come home and reproduce their features. He would get peasants into a room and make them laugh, and would even follow criminals to execution for the sake of studying their ex pression. His knowledge of form was great, for he mastered the anatomy of both men and animals to such an extent that anato mists of to-day can find no fault with his anatomical drawings.

While Leonardo da Vinci was still a youth his father sent him to the studio of Andrea Verrocchio, who was excellent in design but very poor in color. Leonardo soon sur passed his master in painting; for the story , goes that when Verrocchio painted his Bap tism of Christ, he entrusted to Leonardo the painting of one of the two angels who form part of the composition. This task Leo nardo performed with so much grace and expression and with such richness of color that Verrocchio saw himself surpassed and ever after devoted himself solely to sculp ture. One of the earliest works of Leonardo was a Medusa Head which still exists in a Flor entine gallery. The head is represented as lying on the fragment of a rock, foreshort ened, the hair already changing into scaly serpents. It is said that as one looks at this “the ghastly head seems to expire, and the serpents to crawl into glittering life.” (See the cut, p. 75.) But, at the same time that he was doing this thing expressive of horror, he showed his power to express also the elevated and the graceful, by some car toons of sacred and mythological subjects.

The Last Supper. Leonardo Da Vinci

When he was thirty years old and in the prime of his talents, he was invited by the Duke of Milan to come there and make a colossal equestrian statue of one of his an cestors. He was engaged upon this statue for more than ten years, reading ancient writers, studying classic statuary, and making a close study of the movements of live horses and the anatomy of dead ones. It was one of Leonardo’s strongest characteristics, this of taking infinite pains and of never being satisfied with results. He made a vast number of studies for this statue, and many of them are preserved; still no one knows exactly how the statue looked. When he had finally finished the clay model there was no money to cast it, and twenty years later it had entirely disappeared. It was in Milan and for this same Duke Ludovico that Leonardo da Vinci painted the wonderful and justly famous Last Supper, a picture perhaps better known than any other in the world, and certainly the grandest one ever conceived up to his time. This masterpiece was executed in the short space of two years.

It was painted on the wall of the refectory or dining room of the Dominican Convent of Santa Maria della Grazie. Perhaps to no other master piece has time been so unkind. In the first place, Leonardo painted in oils instead of fresco, and that alone would have proved disastrous. But, furthermore, floods have twice inundated the room, the French soldiers under Napoleon barracked there in 1796, and the French officers found a source of amusement in using the heads as targets.

Worst of all the restorers have done their fell work time and again, so that now hardly anything of Leonardo’s own work remains but the general composition. One almost wishes that Francis I. had succeeded in his attempt to remove the picture to France. Mutilated as the picture is, however, the masterful character of the composition is still apparent. There were certain difficulties imposed by tradition, for instance the long table behind which Christ and the apostles must sit. The monks themselves at their meals were seated in exactly the same way facing the picture. But how gloriously Leonardo has met the difficulties!

What interesting rhythm in the groups of three disposed on either side of Christ! What an expressive line runs through the s picture, what perfect balance without rigid ity of symmetry; how beautifully one head and figure is relieved against another; what a master stroke to lean the head of Judas forward so as to throw it into shadow, thus making it all the more sinister! Then, last of all, how daring to put a window right back of the head of Christ, where it might so easily have detracted from it; but how well the head holds and centers the attention by the aid of that very window! Then, how expressive the attitudes and what a variety!

Head of Christ. Leonardo Da Vinci

How charged the whole group seems with the intensely felt moment! Leonardo left the head of Christ uncompleted. His ideals were too high, and he could not satisfy them; but he has left a study, a mere sketch in pastel, now in the Pinacoteca at Milan. Slight as the sketch is, it is the most wonderful head in art. No Christ head has ever reached its height, so charged is it with depth of meaning and spirit. No description of Christ could tell so much as does that pastel sketch. Where have strength and meekness, power and gentleness, sorrow and resignation ever been so wonderfully blended in one face? In all the range of art there is nothing like it. Sketches also remain of the heads of the apostles, sketches all the more precious be cause the picture has been so repainted and repainted. Every one of them individual, but only the larger qualities searched out.

All varieties of emotion are there; how headlong, Peter; how gentle, John; how mean and crabbed, Judas! He is indeed a towering genius who could charge a picture so full of interest, emotion, and variety, but still hold it all in hand, and make it all a unit with a forceful climax. While at Milan Leonardo da Vinci was a powerful influence in the Milanese School. He established an art academy there, and some of the notes written for lectures which he delivered are still preserved. It is be cause his activity centered so largely in Milan and because of his strong influence on the Milanese painters that Leonardo has been classed with the School of Milan.

Of the few Madonna pictures by Leonardo da Vinci, the Madonna of the Rocks, in the Louvre, is the most famous. It is a picture full of the depth of shadow and the glimmer of lights that are so characteristic of Leo nardo. The indefinable smile, which Leo nardo alone could paint, lingers over the mouth of the Virgin.

As might be expected from one so keen in the study of expression, one so able to seize on the individual, we find Leonardo da Vinci one of the greatest portrait painters. His masterpiece in portraiture is the Mona Lisa, that portrait of all portraits. What a beautiful, easy, unaffected pose! What caress of light, and softness of shadow! What searching, well-felt drawing and ex quisite modeling! Every plane of the face is felt, but how wonderfully gentle the transition from one to another! Then, above all, what a living presence is there! The very innermost spirit is in the eyes, and the wonderful smile which tells so much and so little, hovers over the mouth. (See the full page cut, p. 368.) In 1514 Leonardo da Vinci went to Rome on the invitation of Leo X., but more in the character of philosopher, mechanic, and alchemist than as painter. Raphael was at that time painting his frescoes in the Vati can; and with his innate courtesy and gen tleness, he received the venerable master with all marks of respect. Even Leonardo showed the influence of the wonderful young genius in the only two pictures he painted while in Rome. But he felt he was set aside at Rome, he who had been the foremost. Michelangelo slighted him, and that galled him. So he decided to go to France where he was sure of a welcome. He was received by Francis I. with every mark of respect, was loaded with favors, had a pension of seven hundred golden crowns settled on him for life, and was attached to the court as principal painter. He lived like a prince in the castle given him, and received from all the reverence and homage due his wonderful genius. He died in France in 1519.

Florentine and Roman schools: Fra Bartolommeo, Albertinelli, Del Sarto and others

Although the Florentines loved line and intellectual conception more than the more sensuous qualities of color, there were some of them who combined both elements. One who did this in a most remarkable way was Fra Bartolommeo (1475-1517). He was a pupil of Cosimo Roselli, and learned the technique of colors from Leonardo da Vinci.

While young he came under the influence of Savonarola, and one of the first things he did was a portrait of the homely but strong and powerful head of that genius. Many of Fra Bartolommeo’s works have been lost through the fanatical zeal of Savonarola; for in 1497 he induced a good many artists to burn all of their pictures into which any nude figure had been introduced, or which did not happen to have a religious subject.

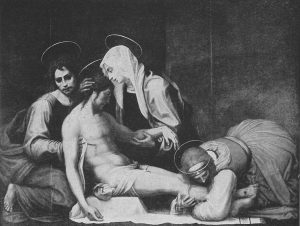

Fra Bartolommeo was one of the first to carry out Savonarola’s wishes. The martyr-dom of Savonarola was such a great shock to Baccio, as our painter was then called, that he joined the monastery of S. Marco, and did not touch the brush again for six years, when his friends at last prevailed upon him to resume it. Fra Bartolommeo had that mark. of a great painter in his work, the union of fine technique (color, drawing and composition) with deep sentiment and feeling. His fine color may be attributed to his visit to Venice, where he studied the glowing harmonies of the Venetians. In light and shade, he was directly influenced, as were so many of his time, by Leonardo da Vinci. He was opposed to the sensuous on prin ciple, but there is a good deal of it in his fine light and shade and in the expressive beauty of his faces. He was opposed to painting the nude, but that he was a master of the human form he proved by the only nude he ever painted, a St. Sebastian. This was so beautiful in form and line and color, and so fine in its modeling and life, that people forgot the suffering of the saint for the beauty of his form, with the result that the prior had to have the picture removed. One of his greatest pictures is the Deposition from the Cross, in the Pitti Gallery.

This is composed on the pyramidal principle, a form of composition found in all Fra Bar tolommeo’s works. The lines marking the masses of drapery are beautiful in flow and disposition, and the light and shade comes up to Leonardo da Vinci’s in beauty. There is a true dramatic breadth about this picture, but it is repressed, held within bounds. (See cut, page 374.) Mantegna, for instance, goes beyond artistic dignity, when in his Burial of Christ he makes John scream out aloud in his grief. In Fra Bartolommeo’s picture the deep, silent, tearless, unutterable grief of St. John is far truer to the dignity and pathos of the moment. Fra Bartolommeo was great by his pure painter-like qualities, but with it fie had a depth of sentiment and fervor of re ligious feeling that mark him above all others of his time.

Mariotto Albertinelli (1465-1520). There was a close friendship between Albertinelli and Fra Bartolommeo, a friendship which lasted for life. They worked in partnership and often painted together on the same pic ture. In such cases it is almost impossible to tell their work apart. Albertinelli lacked the religious devotion of Fra Bartolommeo, but that he painted religious pictures with feeling can be seen from his masterpiece, The Salutation, in the Ufflzi, a picture of much tender sweetness.

Among the followers of Fra Bartolommeo and Albertinelli were Fra Paolo da Pistoja (1490-1547), Bugiardini (1475-1554), Granacci (1477-1543), and Ridolfo Ghirlandajo (1483-1561). Paolo inherited Fra Bartolommeo’s drawings, and made use of them for his own pictures, which are for that reason always good in design; but he did not have Fra Bartolommeo’s mellowness of color, his being rather harsh and crude. His best work is a Crucifixion, at Sienna; a picture which has been attributed also to Fra Bar tolommeo, but which has faults and hardness of drawing not at all characteristic of that master. Bugiardini was an assistant rather than scholar of Albertinelli. In the shop of Ghirlandajo he met Michelangelo, who afterwards employed him as an assistant in the Sistine Chapel. Bugiardini had no original force, but imitated any master with whom he might happen to be in contact. This was also true to a great extent of Granacci, who shows the influence of many masters in his work.

Deposition from the Cross. Fra Bartolommeo

Ridolfo Ghirlandajo, the son of Domenico Ghirlandajo, was one of Fra Bartolommeo’s principal followers. His two masterpieces are the S. Zenpbio Restoring a Dead Child to Life, and the Funeral Procession of the Saint. Here he rivals the rich coloring and deep relief of Fra Bartolommeo, and the animation and expression of Andrea del Sarto.

Andrea del Sarto (1480-1531) was called the faultless painter by his fellow towns-men, and this was true so far as technique goes. As a colorist and handler of the brush he went far beyond the rest of the Florentines. His drawing was perfection, and his mastery of light and shade nothing short of the marvelous. His talent for assimilation was great. He gained in draw- ing from Masaccio and Ghirlandajo, and in line from Michelangelo. Light and shade, as might be expected, he gained from Leonardo da Vinci; but in the matter of strong, interesting, masterful brushwork, and in his coloring, characterized by a subdued, though rich and beautifully soft harmony of secon daries and tertiaries rather than the harsh primaries of his fellow Florentines, he stood entirely by himself. In landscape work and atmospheric effects also he went beyond the other Florentines. But with all his fine technique and wonderful adaptability, he lacked that spark which, had he possessed it, would have lifted his work up to the height of the four giants of the art world. It was the times that made Andrea del Sarto great, his talent rather than his genius.

Browning in his poem of Andrea del Sarto makes his wife the principal cause of his lack of soul, and his pictures give the appearance of truth to the assertion. All his Madonnas (and his subjects were entirely religious) are of one face, beautiful in form, the face of his infamous wife, who was the cause of his dishonor. That Andrea del Sarto was of tremendous promise to his contemporaries we gain from Michelangelo’s remark to Ra phael: ” There is a little fellow in Florence who will bring sweat to your brow if ever he is engaged in great works.” It is unfair to say that Andrea del Sarto entirely lacks soul. His St. John, in the Pitti Gallery, with its luminous depth of eye refutes the charge somewhat. But, on the other hand, in the same gallery is a Madonna, Child and Saints which shows a woeful lack of soul and feel ing, wonderful as it is in the modeling of form, the sweep and beauty of line, the softness of enveloping atmosphere, and the mastery of drawing. The Madonna’s face is of a low type, although of a certain beauty, and is decidedly unpleasant. Andrea del Sarto is perhaps the finest technician in fresco that ever lived. In that he went beyond even Michelan gelo and Raphael.

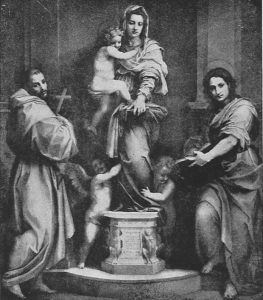

Madonna of St. Francis. A. Del Sarto

He seeme to be able to make fresco do the work ot oils, anü he never retoucneo. Hts master- piece, the Madonna of the Sack, so called from the sack upon which St. Joseph is lean- ing, is a fresco in the Chapel of the Annun- ciate at Florence. In a small, narrow, semi- circular space, so small thai Hie fig mes aie represented seated low down, he has succeeded in placing a composition of great grandeur and power, beautiful in balance and sweep of line. The drapery is superb in arrangement, and the Madonna here it marked by real dignity and even grandeur. The child is also a masterful rendering of lively, eager, yet dignified childhood. His finest work in oils is the Madonna of St. Francis, sometimes also called the Madonna of the Harpies. Andrea del Sarto died poor and alone; for his wife, for whom he had lost honor and the respect of his fellows, deserted him in his last illness He had a large number of pupils and followers, but they deserted him later for Michelangelo. The two most important are Pontormo and Fraaciabigio.

Pontormo (1493-1558) was of great promise, for Michelangelo is reported to have said of him: “If this young man’s life is spared, he will raise our art to the skies.”

But, alas, he did not live up to his promise, losing himself later in life in imitation of others. In fact, imitation, the death of all creative art, was almost inevitable, for the great masters had already said the last word in the art of the time.

Franciabigio was a pupil of Albertinelli, and became a co-worker with Andrea del Sarto, by whom he was greatly influenced, although Andrea was by several years his junior. Franciabigio painted some very fine portraits in oils. His finest work is perhaps the Marriage of the Virgin, in the Annunciate Church at Florence. The monks uncovered this work before it was finished, which so enraged the artist that he attacked it with hammer blows. The head of the Virgin was entirely destroyed, and it has never been restored.

Florentine and Roman Schools: Michelangelo

Michelangelo (1475-1564), one of the world’s four painters, was the most majestic of them all. His great word in art was power. He dealt in the things that are vast, titanic, superhuman. Everything he did, everything he studied, was done for the strength in it. He was the most powerful creative genius that ever lived. He did not care for the imitation of facts; his tremendous thoughts and feelings were put forth through forms, built on the knowledge of facts, but nevertheless created. His figures, huge of limb but not gross, mighty in pose and gesture though not exaggerated, without human prototype still instinct with life whether in repose or in motion, impress one with a vast, unexplainable-power, with a might like the grandeur of huge architectural creations. He himself was a stern, rugged, grand, unflinching character, who carried art to its highest pinnacle, and lived long enough to see the mighty impulse, which culminated in him, shatter and break and become mere imitation and mummery in those that tried to follow his vast flight. He was more of a sculptor than a painter in that he did not care for the more sensuous charm of color and atmosphere; but his architectural decorations gain all the more in that he leaves out the matter of atmos phere and consequent illusion. In grandeur of composition he is of the best, and in drawing he stands supreme. Weak of body, his inflexible will and temper account for his immense productivity. Michelangelo was born near Florence. Of noble family, his father, a poor man, wanted him to adopt the profession of notary public or advocate rather than that of artist, for which he had great contempt.

But the spirit within the boy was not to be denied. He neglected his irksome studies, and spent a great deal of his time in artists’ studios, mastering art as best he might by himself, until. Ghirlandajo, who saw the wonderful power in the boy, pleaded his cause so well that his father at last con sented, and Michelangelo entered Ghirlan dajo’s studio at fourteen. Here Ghirlandajo paid him a small sum for his help instead of charging for tuition as was usually the case. When fifteen Michelangelo was selected among other fortunate youths to study in the academy which Lorenzo the Magnificent had established in his garden under the charge of Bartoldo, the sculptor. He instantly caught Lorenzo’s attention by his Satyr’s Mask, and that patron of art offered to take the young genius and care for him. With Lorenzo Michelangelo heard the con versation of the greatest men of the day, and this must have wonderfully stimulated his youthful mind. His activity was directed entirely to sculpture until 1503, when he entered into direct competition, if so it can be called, with Leonardo da Vinci in car toons for the decoration of the Town Hall of Florence.

Leonardo da Vinci chose as a subject the defeat of the Milanese by the Florentines in 1440. Here he could intro duce his great knowledge and study of the horse. Michelangelo’s subject was a group of Florentines surprised while bathing in front of Pisa, which they were besieging. Powerful figures in all positions, some naked, some half-clothed, form the subject, and it gave Michelangelo full chance to display his great knowledge of the human fig- ure. These two cartoons were never executed in fresco on the walls; but they formed a school for all the artists of the time, and their influence was felt to a power- ful degree in the development of modern art. Both cartoons have perished. Rubens copied from Leonardo’s a group of horsemen fighting for a standard, but he did it in his own Flemish manner. Baccio Bandinelli, a sculptor and rival of Michelangelo, is said to have cut Michelangelo’s cartoons into shreds in a fit of jealousy, but some of the groups are known through old copies and engravings.

In 1506 Pope Julius II. called Michelangelo to Rome. The pope had a magnificent project for his own tomb, and Michelangelo was to execute it; but it was never completed. Bramante, the architect, could not bear to see Michelangelo in favor, and often made him suffer by his schemes and plots. At last he made the pope believe that to build one’s tomb while living was an ill omen, and Michelangelo’s work was thus brought to an end. The pope then commanded Michelangelo to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo protested; for he was a sculptor and no painter, he said, but his pleas were unavailing. He was so diffident about his power as a painter that he invited several painters from Florence to assist him by coloring the decorations from his designs. But, as one might expect, these painters were unable to grasp the style of the giant mind, and in disgust Michelangelo destroyed their work and sent them away.

It is said that he spent only twenty-two months on this gigantic undertaking—the ceiling was 150 feet long and 50 feet wide—but others estimate that it took three or even four years. On the surface of this ceiling, which is a flattened arch in section, he painted in all about two hundred figures, some of colossal size. (See the cut, p. 43.) The center of the ceiling, which is a flat plane, is divided into nine compartments, four large and five small. In the large compartments he has represented the Creation of Sun and Moon, the Creation of Adam, the Fall, and the Deluge. In the small compartments are represented the Gathering of the Waters, the Almighty Separating Light from Darkness, the Creation of Eve, the Sacrifice of Noah, and the Drunkenness of Noah. In the curved part are represented, besides the genealogy of Christ, the colossal figures of sibyls and prophets, and in the four corners are scenes representing the miraculous deliverances of Israel.

Decorative figure in the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo

All these figures and scenes are contained in a well composed strong architectural framework. There is not one figure or portion in it but has its own interest, and yet it is all ordered and unified into one grand whole. It took one with the gifts of a great sculptor, architect and painter to keep this vast space, so crowded with interest, from being scattered; but Michelangelo had them all, and with well-defined spaces and strong leading architectural lines, which emphasize each scene at the same time that they unite them, he has produced a decoration that is one of the marvels of the world in its repose in action.

The first three compositions, the Drunk- enness of Noah, the Deluge, and the Sacri- fice of Noah, are smaller of figure than the other compositions. This is especially true of the Deluge. Michelangelo evidently started at this end of the ceiling, and, finding that the figures in the Deluge could hardly be seen from below, altered the scale in the other compositions. The triangular compositions representing the ancestors of Christ are interesting as being gentler and tenderer than is Michelangelo’s wont. These are really idyllic family groups, wherein some of the female figures are full of grace and beauty.

The seated architectural figures are marvelous in their variety of pose and strength, and with the sibyls and prophets we come upon some of the mightiest figures known to art. But the climax of all the figures is reached in the Adam of the Creation. (See the cut, p. 369 ) In all art there is nothing like it save the grandly god-like figures of the Parthenon pediment. Mighty is the form as it lies stretched on the rim of the world, powerful and huge, but what grace witbal in every supple line! Nothing else could be worthy of the father of a race. There is that about Michelangelo’s work which creates a mood like that one falls into when viewing some overpowering scene of nature, some mighty mountain range or grand sweep of ocean.

It is no wonder that Sir Joshua Reynolds said of Michelangelo: “To kiss the hem of his garment, to catch the slightest of his perfections, would be glory and distinction enough for any ambitious man.” Michelangelo did not paint again for twenty-two years, but in 1534 Paul III. decided to have the Sistine Chapel finished, and Michelangelo, again interrupted in his work as a sculptor, now painted on the end wall of the chapel his Last Judgment, a picture sixty feet high. The composition was part of Michelangelo’s scheme, and had always been intended by him. In mastery of form, in power of drawing the figure in the most difficult positions, this work is unrivaled; but it docs not have the well- ordered dignity of composition which dis- tinguishes the ceiling decoration. All is grewsome despair in this conception. There is no ray of joy; even the blessed are weighed down by the doom of the condemned.

The Christ figure is awe-inspiring in its expression of terrible wrath. In this composition Michelangelo indulged to the fullest bent his love for the nude figure, but there seem to have been prudes in those days as well as now. Pope Paul IV., who did not care for art at all, wished to have the painting destroyed; but a compromise was effected by having Daniele da Volterra paint draperies over some of the most ‘’objectionable-‘ figures, a deed which earned him the title of brccches-maker.

The last pictures Michelangelo executed are the two frescoes in the Pauline Chapel of the Vatican, The Crucifixion of St Peter and The Conversion cf St. Paul. These are so blackened by incense smoke, and so badly preserved generally that they are rarely even mentioned. Michelangelo did only one easel picture, a Holy Family. It shows the mastery of difficult posture and anatomy, as does all of Michelangelo’s work; but it lacks the tenderness and feeling that one expects from such a subject The Fates and other easel pictures given as being Michelangelo’s were painted by his pupils and followers, some- times from his designs, but often in iraitation of him. Michelangelo led his lonely and stern life to the last, a giant among men, never swerving from his purpose, always true to himself.

His path in art was entirely orig- inal, the expression of a tremendous person- ality, an individual temperament. It is in this intense individuality of temperament that he is so modern, and comes so near us at the present time. Grimm says of him: “All Italians feel that he occupies the third place by the side of Dante and Raphael and forms with them a triumvirate of the greatest men produced by their country,—a poet, a painter, and one who was great in all arts.

Who would place a gen eral or a statesman by their side as equal to them? It is art alone which marks the prime of nations.” Michelangelo’s tre mendous personality exerted a powerful in fluence on all the paint ers of his time, even the “divine” Raphael falling under his spell. But the direct imitators failed sadly; for where he expressed tremendous power and awein spiring grandeur, they would sink into mere exaggeration and gross ness. A few of his followers, however, showed some independence and painted things of some strength.

Florentine and Roman Schools: Volterra, Venusti, Piombo

Dantele da Volterra (1509-1566) was the strongest of them. His great pic- ture is the Descent from the Cross in S. Trinita de Monte at Rome. Poussin classed it among the three pictures of the world— rather an absurd statement. The picture is full of action and passion, but almost too violently so; and there is a certain affectation in pose and gesture. It is so much better than other pictures by Daniele da Volterra, that the design is in part ascribed to Michelangelo.

Marcello Venusti (1515-1585?) painted a number of pictures directly from Michelangelo’s designs. His technique was smooth and finished, and forms a peculiar contrast to the powerful designs of Michelangelo. Certain characteristics of Michelangelo, for instance the bended wrist, become an unpleasant reiteration in some of his followers. In the Holy Family (or Silence) of Venusti, for instance, the pose of the Virgin’s hand is sprawly in fingers, and the pose of the hand of St. Joseph and of the Christ child is decidedly monotonous and tire- some. His copy of Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, in the Gallery of Naples, was made under Michelangelo’s own superin- tendence, and is of especial interest ’now that the original is in such a bad state of preservation.

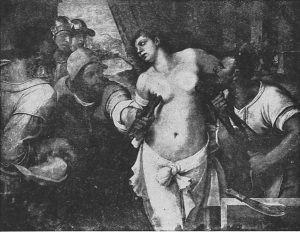

Martyrdom of Saint Agatha. Piombo

Sebastiano del Piombo (1485-1547) was another strong follower of Michelangelo. Born in Venice and trained under the strongest painters there, he had the fine color and light and shade qualities of the Venetians.

These he tried to unite with Florentine grandeur of line, after coming to Rome and falling under Michelangelo’s influence. The yielding softness and texture of flesh so distinctive of the Venetians was also Sebastiano’s, and in that he is much different from Michelangelo. The mastery of the mystery of light and shade is also his, and like Giorgione, his early master, he loves to dwell on the glint of light on armor and its glimmer on soft flesh. It was his ability to render the more sensuous, the beauties of nature, that gave rise to the story that Michelangelo once designed a picture for Sebastiano to paint, so that thus Raphael might be outdone. Sebastiano was really a wonderful portrait painter. Here he combined the color of Titian with Michelangelo’s style of drawing. His masterpiece is supposed to be the Raising of Lazarus, in the National Gallery, London.

Florentine and Roman Schools: Raphael

“Raphael (1483-1520) the Prince of Painters,” “Raphael the Divine” are names given again and again to this one of the quartet of the world’s painters. “The harmonist of the Renaissance,” he is also called, and rightly, for his great aim was to produce a union of all elements into a perfect whole. For the same reason he was also called the “Greek of the Renaissance.” The passionate fiery expression of individuality by Michelangelo is not Raphael’s. He stands more apart from his creations, he views them more critically. Feeling is tempered by thought, by regard for canons and established laws of proportion. Not that Raphael is cold, for his works are full of feeling; but he is more serenely calm, more tempered, more regardful of an exact balance, rhythm and union of feeling, thought, form, proportion and expression. Michelangelo is subjective entirely; Raphael is objective. With him the personal element is kept in the background. The headlong, passionate working out of a mood was foreign to Raphael; he worked more deliberately, added one thing here, another there, held himself always in check, and saw to it that nothing had undue prominence, that nothing was one-sided. His figures are grand, majestic, serenely powerful, but not mighty, passionate and titanic, like Michelangelo’s.

He was more of a painter pure and simple than Michelangelo. For a Florentine his color was good, his light and shade had the beauty of nature’s mysteries in it, envelope also was at his command, and in drawing and composition he was grand, forceful. For grace, lofty serenity, purity and beauty of line and form he stands supreme. It is not that Raphael did all things better than any one else that makes him supreme, but it is the wonderfully harmonious union of all excellencies in him. Titian had better color, and far better brush work, Michelangelo greater power, vaster thoughts, Leonardo da Vinci perhaps more charm and feeling; but none other than Raphael has possessed all these qualities. We should expect a fine character and an even temperament from a man who produced work like that, and Raphael had both.

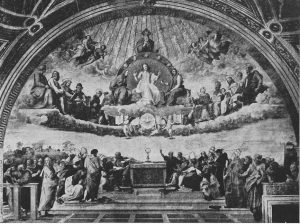

The Disputa. Raphael

There was nothing crabbed or mean about him. His spirit was true, sweet and wholesome, and he felt no jealousy of the attainments of others. To all he gave their due, and he paid homage and deference to paint- ers who were older than he, but whose art was far below his own. It has been well said of him, “Every grace of mind and hand was Raphael’s.” He saw the good in other artists’ work, and would assimilate from them, but not imitate. He made their various qualities his own; they bear the stamp of his individuality. In studying Raphael’s work one finds that it passes through three distinct styles. The first is the Peruginesque. This manner characterized him while he was directly under Perugino’s influence and for some time after. The second is the Florentine manner, acquired during his visit to Florence and while under the influence of Fra Bartolommeo and Leonardo da Vinci. The third is the Roman manner, which becomes characteristic of him after his coming to Rome and feeling the influence of Michelangelo’s work. His greatest works are those of the Roman Period.

Raphael was born in the city of Urbino. His father, Giovanni Santi, gave him his first training; but Giovanni died while Raphael was still young, and his uncle decided to place him with Perugino, who was then at the height of his fame. It is said that Perugino exclaimed upon seeing Raphael’s sketches: “Let him be my pupil, he will soon become my master.” Raphael was less assertive than Michelangelo. His progress was gradual and there is no indication of the force and strength and grandeur of his Roman period in his Marriage of the Virgin, the best-known picture of the Peruginesque period. There is far more life than in Perugino’s work, greater beauty of drawing and expression; but there is the wistful, mild sweetness of that master, the same slight affectation in tilt of head and the same lack of dramatic force. The young man, for instance, breaking his rod, shows no agitation, no vigor of pose.

There is also the same simple symmetrical composition which distinguishes Perugino’s work. It is Perugiuo’s style carried to perfection. It was about this time (1504) that Raphael made his first visit to Florence. Here he became acquainted with Fra Bartolommeo, and saw the cartoons of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. It was a powerful stimulus to Raphael, and revealed to him new ideas of form and composition. His work became far stronger in line and action, and grander in form. There was more of nature, affectations were dropped, and certain peculiarities in handling of draperies disappeared. The St. Catherine of the later Florentine manner, now in the National Gallery, London, is a splendid contrast to the Marriage of the Virgin. That looks weak beside it. The strength of pose and free, grand swing of line and natural fullness of form in the St. Catherine makes an agreeable contrast to the Marriage of the Virgin.

There is still the Peruginesque feeling, but it is less sentimental, far more virile and much loftier. This can be seen to the full in one of the most famous pictures of the Florentine manner, The Madonna of the Goldfinch. Graceful and sweet in expression, it has besides a strength which places it far above Perugino’s rather weak works. The face has the regularity of classic art, but far more warmth of expression. The beautiful pure line and form is such as Raphael alone mastered. The head of the Christ child is not successful when compared to that of the child in the Madonna di San Sisto. It looks almost unhealthy beside that, and too strained in the effect of expression.

The equally famous La Belle Jardinière. in the Louvre, is far more successful in the Christ child, here entirely natural, but without the peculiar something which makes the Christ child in the Madonna di San Sisto supreme. Moreover, the light and shade in La Belle Jardinière is far stronger. It is impossible to describe the beautiful flow of line and the tender modeling of form in this picture. (See the full page cut on p. t8ç). Whereas Michelangelo seems to have hewed out his mighty lines, Raphael appears to have loved his into being, so gracefully do they flow and ripple one into the other, so fraught are they with feeling and tenderness.

Many artists of the Renaissance reached full prime early in life. Whether the greater stimulus of a universal appreciation of art or whether peculiar training was the cause is hard to say. There is one thing certain, however, that art training was begun earlier. When Raphael was twenty-five years old his fame completely filled Italy. He had then entirely emerged from the Peruginesque manner, based his work on nature, rather than on the traditions which governed Perugino, and had far greater scope than that master. It was now that Bramante, the architect, saw that his fellow townsman had become strong enough, and he recommended Raphael to Pope Julius II to decorate rooms in the Vatican. The youthful Raphael saw the mighty frescoes of Michaelangelo and fell under their powerful spell, and it is from this time that his third manner, the Roman, dates. The new element, the grandeur of Michelangelo, appeared, and now there sprang from under his wonderful brush those creations from which succeeding artists have borrowed something or other, but which none have been able to equal, much less improve upon. There were four of these halls or stanzas which Raphael decorated. They had already been partly decorated by Perugino and Francesca; but when Raphael had finished the first stanza, the pope was so astonished and delighted that he commanded that all the former frescoes should be destroyed and that Raphael should decorate the entire hall. This Raphael refused to do. He venerated his old master, and it was foreign to him to slight what had been done by others. The first stanza to be decorated was the Judicial Assembly Hall, called “La Segnatura.” Here he painted in grand allegories representations of Theology, Poetry, Philosophy and Jurisprudence.

Four allegorical figures representing these abstractions appear in circular spaces on the vaulted ceiling. Under these figures and on the tour sides of the room Raphael painted four great pictures about fifteen feet high by twenty-five feet wide, illustrating historically the four allegorical figures above. The allegorical figures are painted against a gold background which is treated as a mosaic. The figure of Poetry and that of Theology, or Knowledge of Divine Things, are the most beautiful in line and pose. There is an indescribable grace about these figures, an earnest, gentle seriousness and serenity. For a gentle rhythmic flow of line, so that one takes up where another ends, Raphael has never been surpassed.

The large wall decorations in this stanza illustrate the progression of Raphael’s style, a progression so rapid that it becomes apparent even in this single room. Under the figure of Theology is the so-called La Disputa del Sacramento, which should rather be called Divine Inspiration. This was the first painting that he did. Next came the Parnassus, painted under the allegorical figure of Poetry. Here we find the painting less minutely done, with less of the old clinging to it. With the School of Athens, placed under the figure of Philosophy, we reach a larger style and grander composition, with the general mass thought of more than the detail. There is something majestic, however, in the line of Saints in the Divine Inspiration, as it sweeps in a curve from one side of the composition to the other, and divides the field in a peculiarly happy proportion of space. This line is again beautifully opposed by the extended line of prelates, sages and students underneath. It is this thorough understanding of the necessities of clearly divided spaces and strong leading lines enclosing different elements of the composition that makes Raphael’s decorations so truly architectural in spite of the fact that they arc “holes” in the wall. That Raphael has clung to gold ornamentation and certain other conventionalities in the upper part of this composition, is no doubt due to the absolute impossibility of depicting such a scene with anything but symbols. How wonderfully the main axis of the composition is kept through the figure of Christ, and how well all the lines lead to that figure, any one can perceive. The Parnassus is composed over and on each side of a window. The composition here has the rhythmic grouping of figures so characteristic of the Last Supper, by Leonardo da Vinci. Although subdivided into groups, the composition has a wonderful unity, the total line made by the several groups beautifully fitting the architectural setting and the space to be covered.

The School of Athens is the most impressive of the four compositions. It is truly great in dignity of line and mass. The figures are grand beings, elevated above the common, beings who impress one with powers beyond the ordinary. Again there is the same ordering of the separate parts, the same unity; but the composition has even more stability and architectural weight. The different groups are varied and full of interest The two central figures, Plato and Aristotle, are grand in form and ges- ture, and are a worthy climax to it all. On the whole this is perhaps the grandest composition, the most sublime, of all the stanzas.

The fourth composition under Jurisprudence had to meet the same difficulty as the Parnassus. A large window breaks up the space, but instead of being covered with one composition this wall is divided into three separate pictures. Directly under the ceiling and enclosed by the arch are represented Prudence, Fortitude and Temperance, as virtues necessary for the application of law to daily life. At the sides of the window is represented the Science of Jurisprudence, in its two divisions of ecclesiastical and civil law. Justinian on the left represents state law, and Gregory XI. on the right ecclesiastical law.

The picture in the arch, without being so majestic in composition as the others, is magnificently beautiful in grandeur of figure, in beautiful roundness of form, in fine arrangement of drapery, in a wonderful balance and opposition of line and mass, and above all by a flow and rhythm of line which ripples through the whole composition. It was not till the year 1510 that Raphael commenced the second stanza, called Stanza dell’ Eliodoro, from the most famous composition in it. The pictures in this room arc the Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple, the Mass of Bolsena, the Attila, and St. Peter Delivered from Prison.

The last named, besides being a fine dramatic rendering of the subject, is a masterful rendering of conflicting lights, of the sheen on armor, and of the vigor of attitude. The figure of the angel leading St. Peter from the prison is a peculiarly strong yet beautiful one. The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple is the strongest among the compositions of this stanza. Here the dramatic element is still more evident. The rush of the angels bent on their errand of punishment, and the agitation of the spectators are finely given. The beautiful wrathful being on the horse is fine in power of form and vigor of pose. The Stanza dell’ Incendio was done in great part by Raphael’s scholars from his designs. Commissions poured in upon him in such numbers that he was unable to do much but direct the work of his scholars and furnish the designs. He had, moreover, suc- ceeded Bramante as architect of St. Peter’s, and his hands were too full. The work in this stanza progressed so slowly that the fourth chamber, the Sala di Costantino, was not completed until after his death. In the Stanza dell’ Incendio was painted the Vic- tory at Ostia over the Saracens, The Oath of Leo III., Charlemagne Crowned by Leo III., and The Fire in the Borgo.

The Fire in the Borgo is the most remark- able work in this stanza. It shows perhaps most thoroughly of all Raphael’s work the influence of Michelangelo in powerful forms and anatomical rendering. In particular the figure of the woman to the right is a powerful rendering of form and windswept drapery. The agitation and varying degrees of despair in the single figures are wonderfully rendered, and there is still a well-balanced, well-united composition; but in some of the other pictures in this stanza begin to be seen the germs of the tendency so soon to ruin the art of Italy,—a striving for dramatic effect at any cost, an exaggeration of muscular development and action.

The Victory over the Saracens, for instance, lacks the stability of mass and gran- deur of line so essential to a monumental decoration, and in the Sala del Costantino, which was done after Raphael’s death, and in which his designs were deliberately altered, there is visible a positive degeneracy. Crowded, restless and confused compositions displace the grand ma jestic, architectural compositions of the Stanza del Segnatura.

There is a striving to show anatomical skill, to make a ‘figure pow erful by exaggerating form, and the execution is much more careless and coarse. The Loggii, of the Vatican, open galleries running around three sides of an open court, were also decorated by Raphael’s scholars un der his personal direc tion. The entire series of pictures here is called Raphael’s Bible.

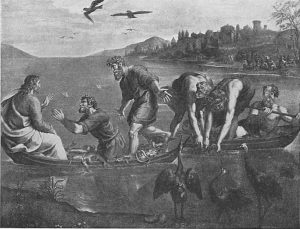

Miraculous Draught of Fishes. Raphael

There was still one more great undertaking that Raphael did for the Vatican. That was making the cartoons for tapestries for the Sistine Chapel. The lower walls of the chapel had been ornamented with paintings in imitation of draperies, but Leo X. resolved to substitute real draperies of the most costly material, and he commissioned Raphael to design the cartoons for them. These were to be copied by the looms of Flanders, and worked in a mixture of wool, silk and gold. In spite of their costliness of material, all the tapestries together are not worth one of the cartoons; yet for a long while these were lost or forgotten in the dusty warehouse of the weaver at Arras. Three of these invaluable cartoons were never recovered, but the remain, ing ten, after running many risks of destruction, came by the advice of Rubens into the hands of Charles I of England. They are now in the Kensington Museum.

The subject of the designs is the history of the Apostles. Richardson says about the figures in these pictures that they are a sort of people superior to what one has ever seen. “What grace and majesty,” says he, “is seen in the great Apostle of the Gentiles in all his actions, preaching, rending his garments, denouncing vengeance upon the Sorcerer! What a dignity is in the other Apostles wherever they appear, particularly the prince of them in the cartoon of Ananias! How infinitely and divinely great, with all his gentleness and simplicity, is the Christ in the boat! But these are exalted characters, which have a delicacy in them as much beyond what any of the gods, demi-gods, or heroes of the ancient heathens admit of, as the Christian religion excels the ancient superstition!” The younger Richardson compares the frescoes of the Vatican Stanza with the cartoons, and says about the latter, “They are better painted, colored and drawn; the Composition is better, the airs of the heads are more exquisitely fine; there is more grace and greatness spread throughout; in short, they arc better pic- tures, judging them only as they arc commonly judged of, and without talcing the thought and invention into the account.”

Sir Charles Eastlake says: “As designs they are universally considered the finest inventions of Raphael. At the time he was commissioned to prepare them, the fame of Michelangelo’s ceiling, in the same chapel they were destined to adorn, was at its height; and Raphael, inspired with a noble emulation, his practice matured by the execution of several frescoes in the Vatican, treated these new subjects with an elevation of style not perhaps equaled in his former efforts. The highest qualities of these works are undoubtedly addressed to the mind, as vivid interpretations of the spirit and letter of the Scriptures; but as examples of art they are the most perfect expressions of that general grandeur of treatment in form, composition, and draperies, which the Italian masters contemplated from the first, as suited to the purposes of religion and the size of the temples destined to receive such works. In the cartoons this greatness of style, not without a due regard to variety of character, pervades every figure, and is so striking in some of the Apostles as to place them on a level with the Prophets of Michelangelo.”

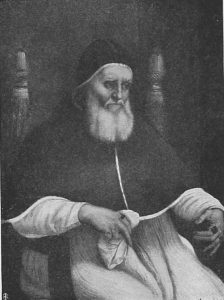

Portrait of Pope Julius II. Raphael

Raphael’s greatest easel pictures are from his Roman manner. Among them are some wonderful portraits. The Fornarina, a portrait of Raphael’s supposed mistress, Pope Julius II., and Pope Leo X. are among the best. In these portraits one receives an additional proof of the wonderful range of Raphael’s art. One who is essentially ideal in his treatment of figures, ordinarily so that they are very impersonal, here comes out in strong realistic rendering of individuality and personality—the very essence of the man portrayed. What a difference between the two popes! One rather coarse featured, round jawed and fat, but with wrinkled brow and tightly-clipped lips denoting great determination and will power; the other old and bent, refined of feature, but with deep, serious eyes denoting purpose, set under the overhanging, reflective brow. Then how splendidly Raphael has rendered the textures, he who has been accused of not knowing how to render them! Here the varying qualities of texture in fur, velvet, hair, metal, etc., are given with the utmost fidelity.

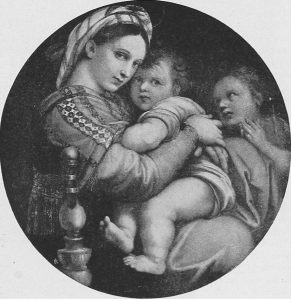

To the Roman period belongs also the celebrated St. Cecilia, a picture futl of indescribable sentiment, with noble forms and expressive attitudes. Notice, for instance, the ecstatic uplifted face of St. Cecilia, and her graceful, beautiful form, the powerful brooding figure of St. Paul, so majestic in its swing of line, and the highstrung, soulful, inspired head of St. John. What a contrast these strongly-moved but quiet figures to the St. Michael and Satan in the Louvre, where the beautiful form of the Angel appears like a flash on the groveling demon. Raphael’s Madonnas are the greatest in all art. Here also how magnificently varied he is! Some arc the joyful mothers of the earth, some are wistful and lender, others are the divine being who is to be worshiped. The Madonna della Sedia, “of the Chair” and the Madonna di San Sisto or Sistine Madonna are the best known. The former is a circular composition, and it is a wonder ful adaptation to its field. There is an ex quisite tenderness in the way the mother caressingly bends her head down to her child’s.

Madonna Della Sedia (Chair) or Secgiola (little chair). Raphael

But the greatest of all the Madon nas is the Madonna di San Sisto, now in the Dresden Gallery. Here is the most won derful representation of a divine child and a divine mother, divine but still human, with the power to sympathize with the hu man. Never has the Christ child been so ex altedly treated. Truly a child; there is still an indescribable depth in the eyes, which be speaks worlds of thought and power. How ten der and sympathetic the mother through all her majesty; how sweet and humble the reverence of St. Barbara, as she sinks to her knees in adoration; how trustful and expressive in atti tude the Pope, as he intercedes for humanity outside.

The composi tion is a marvel of grace, rhythm, flow, and bal ance of line, and the drapery is managed with a wonderful skill, so that although every fold falls in just the right place, it still looks as if taken directly from nature. The glory of innumerable angels’ heads in the background lends a ra diance to the whole composition; and the two cherubs below bestow a charming note of naive, childlike seriousness, besides filling out the composition in just the right place. Raphael had the good fortune to be fully appreciated while still living. His com missions were innumerable, and he became rich. It was said of him that he lived rath er like a prince than a painter; but his spirit was always the same: gentle, courteous, kind, free from all petty jeal ousy and ill-feeling. When he went to the Papal Court it is said that fifty of his pupils and fellow workers al ways attended him as though they were his retinue, and they glo ried in doing him such homage.

His life be came so busy that many pictures left his studio which were not done by him, but which were attributed to him. Then those who were jealous of him would insinuate that Raphael was losing power, that his mastery was declining. Thus, it is said, he decided to paint a picture entirely by his own hand which should forever refute the accusation. This was the Transfigura tion, which, it is further said, he painted in in direct competition with Michelangelo.. The story goes that the latter desired to put Sebastiano del Piombo forward as no unworthy rival of Raphael; but to in sure good design he composed and drew in the picture himself, much to the delight of Ra phael, who expressed pleasure at the austere Michelangelo himself entering into compe tition with him. Although profound in thought and beautiful in execution, while tremendously expressive in action and ges ture, and full of dramatic force, we still feel in the Transfiguration a lack of the sim plicity and unity of composition so essentially a usual characteristic of Raphael.

Madonna Di San Sisto. Raphael

Here one sees really two compositions, in no par ticular way tied together except by the thought contained in the scenes depicted. Pictorially it is two compositions. The restlessness of drapery in the three floating figures also mars the sublimity of the con ception. Kugler, however, says: “The twofold action contained in this picture, to which shallow critics have taken exception, is explained historically and satisfactorily merely by the fact that the incident of the possessed boy occurred in the absence of Christ; but it explains itself in a still higher sense, when we consider the deeper, universal meaning cf the picture. For this purpose it is not even necessary to consult the books of the New Testament for the explanation of the particular incidents; the lower portion represents the calamities and miseries of human life—the rule of demoniac power, the weakness even of the faithful when unassisted—and points to a superior power. Above in the brightness of divine bliss, undisturbed by the suffering of the lower world, we behold the source of consolation and redemption from evil.” All of this, however, deals only with the intellectual phase of the subject and does not do away with the feeling, that pictorially the composition falls short, in that the eye must force itself from one point of interest to another, and that there is no single climax, no one center of interest to which everything should lead.

It is indeed a wonder that Raphael in his short life should have been able to accomplish so much. Besides his painting, he was architect of St Peter’s after Bramante’s death; he designed several works in sculpture; and he conducted excavations which brought to light the treasures of the old Rome hidden underground. It was while engaged in this last work that he exposed himself so that he was taken with a violent fever, and died after fourteen days’ illness on his birthday, April 6th, thirty-seven years old. All classes grieved over his premature death, and the grief of his friends and scholars was unspeakable. It is said that the pope, upon hearing of Raphael’s death, broke out into lamentations over his own and the world’s loss.

After lying in state with the picture of the Transfiguration, still wet and unfinished (afterwards Completed by Guilio Romano) suspcuded over his head, his remains were carried to the church of the Pantheon, a multitude of all ranks following in a sad procession, and was there interred as he himself had requested. Painters had poured into Rome from all quarters of Italy during Raphael’s lifetime, and they tried to imitate his style closely. After his death this school, the Roman, was scattered over Italy, the conquest and pillage of Rome in 1517 by the French contributing not a little to dispersing them.

But the imitation of a master, as in the case of Michelangelo, proved fatal, what originality they might have had being entirely lost.