COLUMBUS AS HEROIC CRUSADER

The second print in the series following the frontispiece features Christopher Columbus and, like the other prints of the navigators in the series, it is aturated with symbolic imagery and formatted with a central image an a caption below. Here the caption describes Columbus’s accomplishment: ‘‘Christopher Columbus of Liguria. With the terrors of the ocean having been overcome, Columbus has awarded almost all of the regions of the whole other world, which he found by himself, to the Spanish king.’’74 Columbus is depicted as a knight in armor holding a nautical map in one hand and a crucifixion banner in the other. Tritons announce his voyage and Neptune, again the symbol for Columbus’s birthplace, ushers him in toward the shore. Nereids and other sea creatures surround him and Diana, goddess of the moon, leads his ships toward the Caribbean islands under a crescent moon.

Various textual sources could have functioned as Stradano’s and Alamanni’s guides for designing the Columbian iconography. By the late 1580s, one could read about Columbus’s journey in Peter Martyr’s writings, in Girolamo Fracastoro’s (1478–1553) poem about Syphilis (1530), in Oviedo’s History (1526), in Las Casas’s (1484–1566) writings, and in Francisco Lo´pez de Go´mara’s (1511–56) Historia general de las Indias (General History of the Indies, 1552). Giovanni Battista Ramusio’s (1485– 1557) Navigazioni e viaggi (Navigations and Voyages, 1555) included excerpts from many of these sources, and Columbus was included in Andre´ Thevet’s (1516–90) and Giovio’s books of illustrious men in history. His biography was written by his son, Ferdinand (1488–1539), and published in 1571, was recorded by Lorenzo Gambara (1495–1585) in his De navigatione Christophori Columbi (The Navigations of Christopher Columbus, 1585), and was dramatized by Stella’s recent Latin poem about the navigator (1585, 1589).75 Much of the elaborate iconography and the emblematic compositions in the prints can be explained by these literary descriptions of the navigator and his journey. Without the inscription below the image and without Columbus’s name inscribed below his feet, one would have been able to identify the navigator thanks to the various attributes surrounding him. For instance, the flag flying on the mast above Columbus bears his coat of arms. Though not of noble birth, in 1492 Columbus received a title and a ‘‘patent of nobility’’ from the King and Queen of Spain that included the creation of an elaborate coat of arms. In his History, Oviedo describes the coat of arms in great detail explaining how ‘‘the royal arms of Castile and Le´on [were] conjoined with newly-conceded arms and the confirmation of some old arms of his lineage.’’76 Columbus’s arms, therefore, were comprised of the symbols of the castle and the lion for the houses of Castile and Le´on in the upper two quadrants, and of more personal symbols—islands and anchors—for the navigator in the lower two quadrants.

The islands in the arms are then repeated by the islands in the background seascape, and the three anchors depicted elsewhere in the print likely also recall his coat of arms. These details and attributes liken the entire image to one elaborate Columbus impresa. The Christian symbols in the image — the crucifixion banner and a dove with a crusader cross at the prow of the ship — are other significant features of this intricate impresa that correspond with several descriptions of the navigator in contemporary texts. Oviedo in particular refers to Columbus as the bringer of the Catholic faith throughout his texts, explaining in one section of his History: ‘‘For Columbus was the cause of so many good things, particularly the reimplanting of the Catholic faith of Christ in these Indies, forgotten since time immemorial in such far-flung regions.’’77 Las Casas similarly describes Columbus as being endowed with ‘‘divine providence.’’78 Dressed in armor and holding a crucifixion banner, Columbus is depicted as a crusader who brought Christianity to the New World. A passage from Ferdinand Columbus’s biography of his father might define the meaning of the dove in the image as well: ‘‘If we consider the common surname of his forebears, we may say that he was truly Columbus, or Dove, because he carried the grace of the Holy Ghost to the New World that he discovered, showing those people who knew him not who was God’s beloved son, as the Holy Ghost did in the figure of a dove when St. John Baptized Christ; and because over the waters of the ocean, like the dove of Noah’s ark, he bore the olive branch and oil of baptism.

’’ In Stradano’s print the dove could make reference to the Italian meaning of Columbus’s name, the Holy Ghost and the dove that led Noah’s ark. The Columbus print is the only engraving in the series to include these Christian symbols, besides the frontispiece (which also features a dove), and he is the only navigator wearing a full suit of armor, indicating that his role as a Christian crusader was a significant aspect of his commemoration in the print. The mythological gods in the print also possess specific symbolic meanings that can be understood in light of literature written about Columbus. While Neptune at right, like the Neptune on the frontispiece, certainly represents Genoa, the significance of Diana is less overt. J. C. Margolin and Alba Bettini each cite, as the source of inspiration for Stradano’s scene, an excerpt from Girolamo Fracastoro’s poem on syphilis, in which the coast of the New World is first seen under the light of the moon, the jurisdiction of the goddess Diana.80 Fracastoro wrote this allegorical poem in Latin in the early sixteenth century about Columbus and the transfer of syphilis to Europe, and dedicated the first book to Pietro Bembo (1470–1547) and the second book to Medici Pope Leo X (1475–1521). It was first published in 1530 and then subsequently was made available in various other editions throughout the century. It would have certainly been known to the Luigi Alamanni and to members of the Accademia degli Alterati. In Fracastoro’s poem, Diana inflicts syphilis on the central character, Ilceus, and then she, in turn, becomes the guide to syphilitics. Fracastoro describes, without ever mentioning the navigator by name, Columbus’s arrival much in the same way that Stradano has illustrated his approach to the land: ‘‘It was night and the Moon was shining from a clear sky, pouring its light over the trembling ocean’s gleaming marble, when the great-hearted hero, chosen by the fates for this great task, the leader of the fleet which wandered over the blue domain, said, ‘O Moon whom these watery realms obey, you who twice have caused your horns to curve from your golden forehead, twice have filled out their curves, during this time in which no land has appeared to us wanderers, grant us finally to see a shore, to a reach a long-hoped-for port.’’81 In Stradano’s print, as in Fracastoro’s poem, Diana guides Columbus to her land under the moonlit sky. The waters through which Diana leads Columbus’s ships are filled with menacing sea monsters that could also be references to other textual sources about his journey.

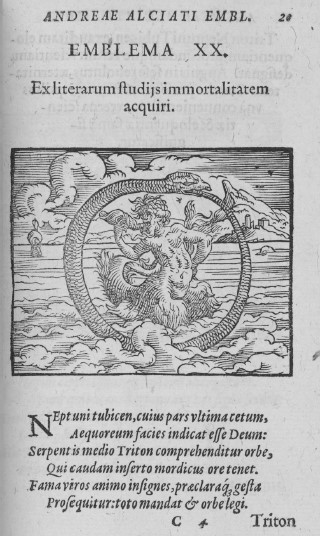

For instance, Ferdinand Columbus describes Columbus’s ship as being constantly surrounded by sharks: ‘‘These beasts seize a person’s leg or arm with their teeth . . . they still followed us making turns in the water . . . their heads are very elongated and the mouth extends almost to the middle of the belly.’’82 Though the monsters that Stradano represents on both sides of the ship do not conform to our contemporary knowledge of sharks, they do recall Ferdinand’s description of the fierce teeth and large heads of the sharks encircling Columbus’s ships. Other sea creatures in the background, also prevalent in the Magellan print, could reveal a continuation of a long tradition of portraying sea monsters in maps and images of the sea as symbols of unexplored and dangerous territories.83 For instance, sea monsters feature in nearly all of the sea imagery in Sebastian Mu¨nster’s (1488–1522) Cosmografia universale, first published in 1544, and in the maps within Ramusio’s Navigationi e viaggi from the 1550s. In editions of Alciati’s Book of Emblems the dolphinlike creature, like the sea-creature with the curly tail in the upper left of Stradano’s composition, represents the dangers of the sea.84 Pliny’s Natural History, a familiar source for sixteenth-century scholars and artists, including Stradano—who refers to it frequently in inscriptions on various drawings — describes in great detail marvelous sea creatures, including sharks, whales, tritons, and nereids in exotic waters in the Indian sea.85

These sea creatures in both the Columbus and the Magellan prints evoke the dangers of the sea in unknown territories, and at the same time likely derive from specific descriptions of the navigators’ journeys. The tritons and the nereids in the image could possess multiple meanings since they resemble creatures represented in art at the Medici court, figures in prints and emblem books, and also textual descriptions of the New World. For instance, Vasari’s allegorical portrayal of Venus (fig. 9) in the Sala degli Elementi in the Palazzo Vecchio from the late 1540s, similarly depicts nymphs riding on satyr-like tritons and male sea gods blowing horns made out of shells. Vasari’s and Stradano’s sea gods could derive from early prints such as Andrea Mantegna’s (1431–1506) Battle of the Sea Gods (before 1481) and printed emblem books that include similar sea creatures. A scene from Grand Duke Francesco and Bianca Cappello’s wedding celebration (fig. 15) similarly illustrated tritons, in this case probably courtiers dressed as tritons, pulling a giant whale or some sort of sea creature in a procession.

Various editions of Alciati’s Book of Emblems employ an image of a triton blowing a shell horn as a symbol for fame or immortality (fig. 16). An inscription below a 1551 edition describes the creature as half fish and half man, announcing fame through his horn.87 Indeed, the tritons beside Columbus’s ship, like the prints themselves, broadcast Columbus’s fame to the world. These tritons could also simply represent New World fish: when de Acosta describes the fish near Lima, hestates that ‘‘they resembled Tritons or Neptunes, who are represented upon

Artist unknown, Parade boat for the wedding of Francesco I de’ Medici to Bianca Cappello, in Raffaello Gualterotti, Feste delle nozze del serenissimo Don Francesco Medici Duca di Toscana et della serenissima sua consorte Bianca Cappello. Florence, 1579. Woodcut. Spencer Collection, The New York Public

Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

the water.’’88 The tritons thus possess at least a dual function in this image: they act as mythological emblems representing fame, and at the same time they symbolize the exotic creatures in the waters surrounding the New World. This anachronistic depiction again pairs fantasy and idealized imagery derived from Medici court culture and from prints with firsthand reports about the voyages to make Columbus’s journey both more plausible and romantic. The gesturing women located in the waters at the left in the Columbus print are featured in all three of the prints of the navigators and represent yet another type of symbolic sea creature.

Because we only see them in bust length, it is difficult to determine whether they are mermaids, sirens, or nereids. Their kind faces and pleasant interaction with one another tell us that they are benevolent and quite different from some of the other more menacing sea creatures in the print. The complex gestures of the women convey that they are telling a story. Perhaps these gestures should be read in a similar way as the emblematic compositions. In the late sixteenth century,

Mercure Jollat, Emblem 133 in Andrea Alciati, Emblematum liber. Paris, 1534. Woodcut. Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor,

Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

gestures were beginning to be codified in handbooks and illustrated texts.89 For instance, Giovanbattista della Porta’s (1535–1615) De humana physiognomonia (1586) discusses the way in which different emotions and states of being are manifested through human expression and gestures.90 Perhaps these women are the Fates, telling the navigators’ stories and leading them to their destiny. In this visual medium, their hands tell the story of the navigators’ travels. The story being told in Stradano’s Columbus print also corresponds closely to Stella’s Columbeidos in terms of both the genre and style of the representation of the navigator. Stella’s poem is the first fictional text on Columbus that incorporates classical elements along with a discussion of the navigator’s Christian mission.

Stella based his poem on Virgil’s Aeneid, even emulating specific lines from the epic poem and referring to the fatum, or fate, that led the navigator like the fate that led Aeneas. Within this classical construct, Stella continually reiterates that Columbus neither came to the Americas to dominate the natives nor to seek out treasures, but rather to bring Christianity to its people. Similarly, Stradano’s image combines Christian symbols such as crosses and the dove in conjunction with representations of the pagan gods. Just as Stella utilizes Virgil’s language and style, Stradano used allegorical and symbolic visual elements, like the sea monsters and tritons, to fictionalize Columbus’s journey. Though the iconography of the image derives from many nonfictional and biographical sources, Stradano emulates the genre and style of Stella’s poem to produce a heroic image of the Italian navigator.

AWAKENED VESPUCCI

The third print in the series, the Vespucci image (fig. 3), must be examined similarly in light of Strozzi’s epic poem about the Florentine navigator. Though sources on Vespucci in the late Cinquecento included Vespucci’s own letters and biographical texts by Thevet and others, it was likely Strozzi’s poem that Alamanni, the Academy, and Stradano knew best.92 Extant today in only one canto, Strozzi’s text, written in Italian rather than Latin, fictionalized and romanticized the tale of the navigator, much like Stella’s text on Columbus. Stradano emulates Strozzi’s dramatic setting and the patriotism implied in the text. Throughout the canto Strozzi describes the rays of the sun that shine through the sky in the dawn and tells of the dangerous waters and fierce winds that Vespucci encountered. In the print Stradano nearly translates this passage visually by portraying a luminous rising sun in the horizon and representing choppy waters. Strozzi writes that Vespucci was born from the river Arno, and Stradano depicts several Florentine symbols to represent Vespucci’s origins: in the background at right, Mars, a symbol for Florence, rides a turtle, perhaps a reference to the Medici motto, festina lente. Another turtle is visible at left in the background, and Minerva, who pushes Vespucci’s ship, holds a giglio, or lily — a symbol for the virgin of Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore — and a spear with a Florentine lily at its end. Later in his text Strozzi alludes to a column broken in the waves. Stradano too depicts a broken columnar mast aboard Vespucci’s ship in the foreground. Stradano has in many ways captured the patriotic fervor, setting, and drama of Strozzi’s poem in his visual rendering of the hero.

Yet other details in the print derive from studies, both of emblems and of other images of the New World, to produce a bizarre conglomeration of allegory and depictions of cannibalism. Stradano transformed the emblematic tritons from the Columbus print into fanciful cannibalistic Native Americans clutching human body parts. Half serpent–half woman and half Amerindian–half European, the New World nereid at the left of Vespucci’s ship wears a peacock-feather headdress as a symbol of her riches and her pride in the way figures representing superbia, or arrogance, do in other sixteenth-century prints. She tames her scorpion tail with the club she holds in her left arm, and with her right arm she raises a human arm on a skewer. The devilish male triton next to her with pointy ears and beard holds a dismembered male torso as if it were a piece of antique statuary, rather than a piece of meat to be devoured. By the late sixteenth century, images of cannibals were widespread in European art, particularly in maps and prints.93

Though it was common since Pliny’s time to represent cannibals with men and women holding body parts on skewers, images rarely (if ever) portray cannibals dressed as mythological or allegorical figures. By doing this, Stradano has represented these New World natives as proud, demonic cannibals, different from the cannibals depicted on mappaemundi and in early Vespucci broadsheets. They are fantastical cannibals that reference anthropophagy but also mask this gruesome practice playfully, in the guise of personifications. In this way their discursive representation acts as nonthreatening figures of fantasy. The two Vespucci prints in the Nova Reperta series (figs. 5 and 6) must be examined here in relation to the Vespucci print in the Americae Retectio because of the commonalities they share with regard to the representation of Vespucci, the depiction of cannibals, and the imagined New World. The Vespucci prints in the Nova Reperta are even more overtly propagandistic than the Americae Retectio works in their praise of the navigator and particularly of his Florentine origin. First, Vespucci is the only navigator portrayed in this series of some nineteen new inventions. Second, most other prints in the series portray a community of people implementing a new invention, whereas in the ‘‘America’’ and ‘‘Astrolabe’’ prints Vespucci is depicted alone as the sole inventor of the New World and the Astrolabe, two things that he did not invent. In the ‘‘Astrolabe’’ print (fig. 6), Vespucci is pointedly connected to the Florentine poet Dante, who in his Purgatory describes the Southern Cross (or four stars), Vespucci’s navigational guide.94 Stradano’s image is divided into two parts: at right a scene represents Vespucci, who stands in front of a desk piled high with his nautical devices and a small crucifix. He gazes up toward the Southern Cross in the sky at an armillary sphere that he holds while his shipmates sleep on the ground beside him.

At left Stradano included a large caption with the passage from Dante’s Purgatory, both in Italian and in Latin, where Dante sees the four stars. Above this an inscription explains that Vespucci cited Dante in his letter and frames a portrait of the poet.95 In his famous letter to Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, which had been published as early as 1502 and enjoyed great popularity in various publications throughout the century, Vespucci describes the use of his astrolabe and writes: ‘‘And while pursuing this, I recalled a passage from our poet Dante from the first canto of Purgatorio, when he imagines he is leaving this hemisphere in journeying to the other. Wishing to describe the South Pole, he says: ‘Then I turned to the right, setting my mind upon the other pole, and saw four stars not seen before except by the first people.’’’96 Alamanni, as a Dante scholar and colleague of Galileo, must have been particularly interested in this Vespucci letter. It was quite likely his idea to emphasize the connection between these two great Florentines in the Nova Reperta print and to have this particular moment commemorated. In his funeral oration for Alamanni, Soldani explicitly connects Vespucci’s voyage to Dante’s journey and describes Alamanni’s fascination for the two travellers.97 By linking Vespucci to the great Florentine poet, Dante, the print produces a claim for the large navigational impact of Vespucci and subsequently of Florence. In the Astrolabe print, the representation of Vespucci recalls two other great men, Christ and Odysseus, two subjects that Stradano also designed for the print series. The sleeping shipmates surrounding Vespucci evoke the sleeping apostles in the Garden of Gethsemane, likening the navigator to Christ.98

The composition of the print also closely resembles another emblem in Alciati that representsOdysseus in the land of the lotus-eaters. In the emblem Odysseus reaches toward a tree while a group of sleepingmen lay below the tree. They represent the men who ate the lotus leaves and, as a result, forgot their homeland. Vespucci is thus portrayed as a hero like Odysseus, who did not forget his homeland, and like Christ, who engaged in prayer in the garden. Vespucci is portrayed in a similarly heroic mode in the well-known ‘‘America’’ print (fig. 5) from the Nova Reperta. However, in this print there is no mention of Dante, and Vespucci gazes, not toward the stars, but toward a semi-nude female personification of the New World. Sharing the same physiognomy as the representations of Vespucci in Stradano’s other prints, Vespucci here looks as if he has just set foot on land and, in a sense, is continuing the narrative begun in the Americae Retectio print. His ship is anchored nearby and his rowboat is beached behind him. In one hand he holds a banner with the Southern Cross and crucifix on a pole, and in the other hand, a compass. America gestures toward Vespucci. She is seated on a hammock and her Tupinamba club leans against the tree at the right. Stradano could have seen these two artifacts from the New World in the Medici collection, since inventories from Duke Ferdinando’s reign reveal that he owned such items.99

Other details, such as the cannibal scene in the background and the various animals grazing in the foreground and background, reflect Stradano’s (or perhaps Alamanni’s) knowledge of the New World, acquired from maps, images, and texts. The representation of cannibals roasting human body parts on skewers over a fire is a more traditional depiction of New World cannibals than the allegorical cannibals in the Vespucci print in the Americae Retectio series. Stradano might have taken this particular arrangement of figures from a small detail in Egnazio Danti’s Brazil map (figs. 17 and 18) in Cosimo’s Guardaroba Nuova that similarly represents two seated men beside a human leg on a spit.100 Michael Schreffler has shown that this scene is borrowed from various other printed views of cannibals, and is correct in pointing out the ‘‘indistinct’’ nature of this representation of the cannibals. Set in the background far from the narrative in the foreground, the scene functions differently than the allegorical female and acts more like a ethnographic symbol of the New World.101 The animals are also ethnographic in conceit. Stradano’s Flemish inscription on the back of the preparatory drawing both labels and describes the animals for the Northern printmakers, and, as previously mentioned, here states that he used Maffei’s Historiarum Indicarum as his source for them. In using and citing this text, Stradano was consciously portraying particular New World animals and sought to illustrate some of the fauna of the Americas more accurately.

The other inscriptions on the preparatory drawing (fig. 7) provide insight into the Latin caption on the final print. The caption on the print alludes to the female seated on the hammock and reads: ‘‘Amerigo rediscovers America, he called her but once and thenceforth she was always awake.’’102 Though the caption is omitted from the recto of the preparatory drawing, it is written on its verso above two other lines in Latin in what appears to be Luigi Alamanni’s hand: ‘‘Tua sectus orbis nomina ducet. Hor. Ode 17 t. 3/ Parsq tuum terre tertia nomen habet. Ovidius Fasto.’’103 As the citations conveniently tell us, these are lines from Horace’s Odes and Ovid’s Fasti.104 The Horace quotation translates to: ‘‘part of the world shall henceforth carry

Egnazio Danti, Brazil, early 1540s. Oil on panel. Florence,

Guardaroba Nuova in the Palazzo Vecchio.

Egnazio Danti, Brazil, early 1540s. Oil on panel. Florence, Guardaroba Nuova in the Palazzo Vecchio (detail).

Europa’s name,’’ and derives from a passage in which Venus tells Europa the news that a continent has been named for her.105 The Ovid passage cited similarly recounts Europa’s story when Venus tells her that ‘‘earth’s third part has your name.’’106 We can speculate that Alamanni devised the caption for the print, using the words of Horace and Ovid as his guide. Vespucci, then, is like Europa and the woman seated on the hammock is an American Venus telling him the significance of his name.107 Indeed, the caption here, like the captions in the Astrolabe print and the Americae Retectio prints, literally defines the allegorical scene. In the preparatory drawing, the word ‘‘AMERICA’’ is written in bold and in reverse on the recto of the drawing just above the cannibal scene and in line with Vespucci’s lips, producing the effect that the words are coming out of the navigator’s mouth, indicating that he is calling out to the New World. At the same time, he names her ‘‘America,’’ which, as Peter Hulme originally remarked and Rabasa has repeated, ‘‘is his name feminized.’’108 We might never know why the Galles omitted this detail from the final print, but its inclusion would have functioned to elucidate the image, and would have corresponded with the caption. Much ink has been spilled about this caption and the representation of America as a nude female awakening to find Vespucci’s gaze upon her. Vespucci’s typical profile has been read as a symbol for the colonial gaze and America’s nudity has been viewed quite rightly as a symbol of her sexual and/or spiritual naivete´.109 Stradano has here used a common sixteenthcentury visual allegorical device, the female nude, to represent a place.110 A nude woman was a common visual trope in the sixteenth century for the personification of the New World.

After all, descriptions of the Americas by Vespucci and Columbus mention that both men and women in the Americas were, like the ancients, unclothed.111 A woodcut from Girolamo Benzoni’s (1519–?) Historia del Nuovo Mondo (History of the New World, 1565) (fig. 19) in which a tattooed nude female is seated among clothed European men illustrates this point.112 The ‘‘America’’ on the frontispiece of Abraham Ortelius’s (1527–98) Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theater of the World, 1570) wears a similar headdress to Stradano’s America and might have functioned as the very source for Stradano’s image. Another semi-nude female New World personification frames many of the portraits in a 1575 edition of Giovio’s Elogia (fig. 13) and could have also been a source for Stradano. Like Stradano’s, these last two representations of the New World link a semi-nude female with cannibalism. In the case of the Giovio and Ortelius images, the iconography is more subtle: severed heads next to the women connote their flesh-eating tendencies. Looking at Stradano’s image within the context of its creation within the culture of print production in late sixteenth-century Europe, it becomes clear that Stradano here was building on a preestablished allegorical depiction of the New World that combined a nude female figure with signs of cannibalism and other attributes related to the Americas. Stradano could have also been commenting on, or unconsciously copying, well-known works by Michelangelo (1475–1564), Florence’s great artist, when he represented America as a nude woman roused from a deep slumber. Jonathan Nelson has convincingly proposed that Stradano

![Marvelous Indian Woman, in Girolamo Benzoni, La historia del Mondo Nuovo. Venice, 1565, 3v. Woodcut. [B917B443], Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.](https://artscolumbia.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Marvelous-Indian-Woman-in-Girolamo-Benzoni.jpg)

Marvelous Indian Woman, in Girolamo Benzoni, La historia del Mondo Nuovo. Venice, 1565, 3v. Woodcut. [B917B443], Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

used Michelangelo’s sculpture of Night from the Medici funerary chapel at San Lorenzo as a model for his portrayal of America, illustrating the parallel between Dawn’s awakening and the discovery of the New World.113 Anne McClintock has also connected the image to another work by Michelangelo, calling the representation of ‘‘America’’ ‘‘a visual echo of Michelangelo’s ‘Creation’’’ and expounding that ‘‘Vespucci, the godlike arrival, is destined to inseminate her with the male seeds of civilization, fructify the wilderness and quell the riotous scenes of cannibalism in the background.

’’ While McClintock has perhaps pushed the analogy too far, Stradano could be referencing Michelangelo’s creation scene and could have connected Vespucci’s discovery and awakening to the Creation. With the nude woman, Stradano has produced an allegorical representation of America in keeping with previous emblematic depictions in other printed sources, and images and iconographic renderings familiar to him. Details in the print and in the preparatory drawing indicate, however, that the woman represented in the print could in fact be a very specific New World figure and that the navigator portrayed could have initially been designed to represent Columbus rather than Vespucci. The first evidence for this hypothesis is an inscription in Stradano’s hand on the verso of the preparatory drawing that states clearly ‘‘De Christoforo Colombo’’ (‘‘On Christopher Columbus’’). Furthermore, in the ‘‘America’’ print Vespucci wears armor beneath his robe.

This costume is unlike Vespucci’s dress in the print dedicated to him within the America Retectio and in the ‘‘Astrolabe’’ print in the Nova Reperta, where he does not wear armor. Both Columbus and Magellan wear armor in the Americae Retectio series. Also, it is Columbus who first planted a crucifix in the New World, as this figure does with the banner. Additionally, there are no references to Florence or Vespucci’s origins in the print, unlike the quite overt ones in the other prints of Vespucci. Finally, the representation of the woman is reminiscent of the Princess Anacaona, a Haitian princess in Stella’s Columbeidos, described as an alter ego to Dido and who, according to various sources, fell in love with Columbus. In Stella’s text, Anacaona falls so deeply in love with Columbus that she cannot fall asleep—and when she finally does, she sees Columbus in her dreams.

She then confronts Columbus with her love, and when Columbus renounces it and sails off, Anacaona faints. Perhaps Stradano is representing a scene from Stella’s verses — either the moment when Anacaona sees Columbus in her sleep, or the moment just before she is about to faint. It is possible that Stradano’s image was initially inspired by Stella’s text about Columbus. If this is the case, the gaze is reversed and it is Anacaona, the representation of the New World, examining Vespucci, a representation of the Western world. Yet it is Vespucci’s portrait that is represented in the America print, and the recto of the preparatory drawing includes the inscribed words ‘‘Americus Vespuccis Florentinus 1497’’ at the feet of the navigator. It is possible that initially the America print was to depict Columbus and to allude to Stella’s romantic epic, but the conception of the print was consequently altered due either to Stradano’s interests or to those of the Alamanni. This might explain why there are two representations of Vespucci in the Nova Reperta series and why Columbus is mentioned on the frontispiece of the Nova Reperta, but not represented in any of its prints.

The emphasis here is evidently on the Florentine Vespucci. America is conceived within this series as a new invention, or reperta, and Vespucci, a Florentine, is considered its true discoverer, even though his travels followed those of Columbus. Within the Nova Reperta, America is tied to at least ten of the nineteen inventions, but interestingly there is no mention whatsoever of Spain, Portugal, or the actual conquest of the Americas in these prints. These works, produced nearly a century following the initial encounter, therefore still conceive of the Americas as a Florentine invention connected to the poet Dante, even though Florence had little or no direct relation with the Americas following Vespucci’s travels.

PIGAFETTA’ S MAGELLAN

The Magellan print, the final work within the Americae Retectio series, represents a non-Italian explorer. Yet the source used to depict the Portuguese Magellan in Stradano’s print is clearly a famous Italian one, Antonio Pigafetta’s (1491–1534) journal of his voyage around the world with Magellan. A native of Vicenza, Pigafetta was the only Italian who participated in Magellan’s journey, and his journal was the most important printed Cinquecento firsthand account of the circumnavigation.116 First published in Italian in Venice in 1536 and then later included in Ramusio’s Navigazioni, Pigafetta’s fanciful text records Magellan’s journey from Spain through the Straits of Magellan to Asia and back to Spain in great detail in the style of a courtly adventure. Because Stradano illustrates specific moments from Pigafetta’s text to represent Magellan, the image reflects more upon Pigafetta than it does upon Magellan. In the print, Stradano truly represents the imaginative journey that Pigafetta describes rather than the voyage of the navigator. Pigafetta’s text, like that of Stella and Strozzi, provided Stradano with the visual content for an allegorized scene that again merges this real voyage with fantasy in a recognizable way through mythological and emblematic representation. Much of the iconography in the print can be linked to specific moments in Pigafetta’s text. Different from the prints of the other two navigators who sail on the open sea, Magellan sails through the Straits that were named for him. Pigafetta vividly describes the ship’s entry into the straits and Magellan’s incredible knowledge concerning their whereabouts.

The fires on the land at the left are labeled in the preparatory drawing as the Tierra del Fuego, which Magellan named because of the campfires of the natives visible from the ship. Pigafetta’s text also certainly inspired the portrayal of a giant seated to the right of the ship putting an arrow down his throat. In several passages Pigafetta describes giants in great depth, and was fascinated by their stature and customs. In one section he relates one of the more unusual actions of the Patagonian giant that Stradano illustrates: ‘‘When these people feel sick to their stomachs, rather than purge themselves, they thrust an arrow down their throat of two palms or more and vomit up a green colored [substance] mixed with blood.’’118 In a later passage, Pigafetta describes a giant bird in China that is capable of carrying an elephant or a buffalo.119 Stradano also represents this bird, the garuda, or roc, with an elephant flying through the sky in the upper left corner of the composition. Rudolf Wittkower suggested that although Stradano could have read about the roc in Pigafetta, he based his visual depiction of the bird on a representation of the roc in a Persian manuscript in Florence.120 Though it is possible that Stradano used this particular manuscript, an image of a bird carrying a creature within Alciati might have also functioned as the source. Other smaller details in Stradano’s print — such as the running native figures along the shore at the right and the various menacing sea creatures in the water surrounding the boat — also recall sections of Pigafetta’s text. Throughout the text, Pigafetta describes natives as gentle beings who go about nude with only a bit of leaves around their waists.121 He also often refers to the menacing fish called ‘‘Tiburons’’ that surround their ship.

Just as Stradano emulated the genre and style of Stella’s text in his Columbus print, and the patriotism and drama of Strozzi’s epic in the Vespucci print, in theMagellan print, Stradano represents specific moments from Pigafetta’s text and captures its fantastical genre. From among these many depictions of the New World and Asia from Pigafetta’s text, Stradano used gods and creatures to aid in telling the tale of the navigator, in the same way that he did in the other prints. Apollo with his lyre functions like Diana in the Columbus print and Minerva in the Vespucci print, and here leads the ship along the coast of Tierra del Fuego. The caption on the print helps define the meaning of Apollo, the sun god, since it explains that Magellan emulated the passage of the sun when he circumnavigated the earth.123 Aeolus in the clouds in the upper right, labeled as such in the preparatory drawing, ushers in a strong wind that pushes Magellan’s ship onward. A triton holding her tail, borrowed from emblem books, recalls the tritons in the Columbus print and represents fortuna. One of the gesturing nereids, or Fates, in the waters behind fortuna mimics her gesture and points in the direction of Magellan’s journey. In the Magellan print, Stradano implements the same format and similar emblematic compositions as the other two prints, but this one differs significantly in terms of its dramatic content. Stradano’s Magellan scene includes many more emblematic compositions in the water, land, and air surrounding Magellan than in the Columbus and Vespucci prints, revealing a design more dense with images, more cluttered, and less refined in terms of its composition. Furthermore, Magellan appears less active and less engaged in his journey than the other two Italian navigators in the series.

Dressed partially in armor, he is seated aboard his ship examining an armillary sphere. This is different from the two other navigators, who stand aboard ship and look out toward the water. A flag with a coat of arms hangs above his head, but rather than a personal coat of arms for the navigator as is the case with the two other prints, the flag above Magellan represents that of Emperor Charles V (1500–58), Pigafetta’s intended audience for the text who ultimately funded Magellan’s journey. A small crusader’s cross flies from the very top of his mast and is the only religious element aboard his ship. Thus Magellan’s journey, unlike those of Vespucci and Columbus, was neither a religious crusade nor a mission to open up new lands. Rather, it was an incredible voyage around the world, fraught with Pigafetta’s magical creatures. The Magellan print in turn lacks the patriotic fervor and the dramatic composition that the other two navigator prints possess.

CONCLUSION

Further study is needed in order to learn more about the reception and use of Stradano’s images, and even to understand his own relation to the New World. It is known that Stradano’s prints made their way to the New World. One of his hunt prints was used as a model for a fresco design in a home in Columbia in the late sixteenth century.124 Furthermore, a printmaker by the name of Samuel Stradanus, likely a relative of Giovanni, produced religious prints in Mexico City in the early seventeenth century in a style very similar to Giovanni’s.125 Perhaps Stradano’s relationship with the Americas transcended his Florentine designs, and perhaps his family traveled to and even worked in this Nova Reperta. Both possibilities, like Stradano’s American prints themselves, are examples of transculturalism, in which images are shaped by cultural and artistic exchange. It is only through the careful consideration of objects within their global context of creation that their complex identities and implications can be revealed. Stradano’s American prints could only be born out of this particular environment in Florence, when the discovery of the New World was a topic of discourse among academicians, and when Grand Duke Ferdinando brought to Florence new books and objects from the Americas.

By establishing the engravings’ relation to the Alamanni and the Accademia degli Alterati, and by demonstrating connections between the imagery in the prints and the production of art, cartography, and literature at the Medici court, the social and intellectual context for the creation of these complex visual allegories is unveiled fully for the first time. An examination of Stradano’s preparatory drawings and inscriptions, and an analysis of the various figures and emblems represented in the prints, demonstrate close associations to contemporary narratives by Stella, Strozzi, and Pigafetta, writings about the nature of the New World by Maffei, as well as the work of Lucretius and Dante. Viewed and read together the images produce a hierarchical fantasy that places the Florentine Vespucci, and therefore Florence itself, at the pinnacle. Though Columbus is referenced on the frontispieces of both the Americae Retectio and Nova Reperta series (fig. 20), he is forgotten in the Nova Reperta print cycle, while Vespucci is fashioned in two separate engravings within the series as a Christ-like figure encountering a new land to awaken. A brief comparison of the three prints in the Americae Retectio

![Giovanni Stradano, Frontispiece for Nova Reperta series, late 1580s. Engraving. [NC266.St81 1776St81], Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.](https://artscolumbia.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Giovanni-Stradano-Frontispiece-for-Nova-Reperta-series-late-1580s..jpg)

Giovanni Stradano, Frontispiece for Nova Reperta series, late 1580s.Engraving. [NC266.St81 1776St81], Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

series demonstrates how drama is purposefully heightened, through composition and iconography, in the Vespucci image in order to emphasize his importance. While the Magellan print is saturated with details that distract the viewer from its seated central character, and the Columbus sheet shows the navigator on languid waters guided by a nonchalant Diana, the Vespucci image reveals a spectacular adventure. His ships travel on an acute diagonal in choppy waters, indicating the force by which armed Minerva propels him with her Florentine lily. Standing in an active contrapposto stance, Vespucci fearlessly confronts the allegorized cannibals before him, while in the distance a rising sun implies hope. The Florentine is the true protagonist of this narrative of discovery. The prints’ captions also contribute to this pro-Vespucci message.

The words inscribed on all three of these Americae Retectio prints identify the great accomplishments of these navigators. Using similar vocabulary and stressing the significance of naming, the captions assign attributions to the new lands in the same way a printmaker or publisher might provide authorship for a particular print.126 The Magellan caption explains that he ‘‘gave a name to the land to the south’’ and that ‘‘his ship was first of all ships to go around the circle of the whole land.’’127 The Columbus caption states that he found these lands ‘‘himself,’’ using the same verb used to describe the designer of a print, inventio.128 According to the Vespucci caption, this navigator ‘‘opened up two parts of the globe amidst omen-filled travels’’ and for this reason Vespucci ‘‘nominavit,’’ or named, the New World. As in the Americae Retectio frontispiece, the Nova Reperta frontispiece is inscribed at the bottom right: ‘‘Stradano has invented these prints as a gift for Luigi Alamanni’’ and ‘‘Philip Galle published them in Antwerp.’’129 Similarly, the roundel at left reads ‘‘Christopher Colvmbus Genvens, inventor. Americas Vespuccis Florent. Retector et denominator.

’’ Here Columbus as ‘‘inventor’’ is likened to an artist who designs a print or discovers an invention, while Vespucci, as ‘‘retector et denominator,’’ is equated with the publisher who makes the design or invention known to the world. Thus Vespucci, like the Galles, who ultimately produced and disseminated the images, is the navigator worthy of most fame. In the Nova Reperta and the Americae Retectio the textual and visual language of printmaking defines the discovery of the Americas, emphatically promotes Vespucci, and exhibits anxiety about invention and the conquest in early modern culture. The Italian city states were hindered from participation in the conquest of the Americas, yet these prints announced Florence’s role in the New World, both implicitly through the imagery and explicitly through their captions. Through the print medium that could be circulated throughout the world, these Florentines laid claim to this unattainable new invention that they were learning and writing about, but that they could not experience firsthand. Here the engravings distinguished the Florentines in particular, and these Italian navigators and writers in general, from the Spanish and Portuguese.

Antiquity, both embodied in the mythological depictions and in the Latin captions, functioned here as a means by which Stradano could represent this still-mysterious New World to an early modern audience, while allegory — evoked through elaborate personifications, emblems, and imprese that mix mythology with cannibalism and the actual travels of these men with references to heroic journeys — acted at the same time to remind the viewer that Stradano’s images were themselves merely false constructions of the past. Through their emphasis on allegory these printed images served as powerful vehicles of cultural propaganda, allowing Florence obliquely to assume a prominent role in the discovery of the New World and appointing Vespucci as the hero of the invention of the New World.