Chapter 7

non additive finite component analysis of concrete BEAMS utilizing ansys package

7.1Introduction

Structural analysis is used to measure the behaviour of technology constructions under the application of assorted tonss. Normally used structural analysis methods include analytical methods, experimental methods and numerical methods.

Analytic methods provide accurate solutions with applications limited to simple geometrics. Experimental methods are used to prove paradigms or full graduated table theoretical accounts. However, they are dearly-won and may non be executable in certain instances. Numeric methods are the most sought-after technique for technology analysis which can handle complex geometries besides. Among many numerical methods, finite component analysis is the most various and comprehensive numerical technique in the custodies of applied scientists today. The finite component method has become really popular among applied scientists and research workers as it is considered to be one of the best methods for work outing complex technology jobs expeditiously. There are assorted finite component packages bundles such as ATENA, ABAQUS, Hypermesh, Nastran, ANSYS etc. ANSYS ( Analysis System ) , an efficient finite component bundle is used for nonlinear analysis of the present survey. The chapter discusses the process for developing analysis theoretical account in ANSYS v12.0 and the process for nonlinear analysis of strengthened concrete constructions is discussed. An effort is made to compare the experimental consequences with the consequences obtained from finite component mold.

7.2 Stairss involved in Finite Element analysis

Finite element analysis involves three phases of activity: preprocessing, processing and station processing.

7.2.1 Preprocessing

In preprocessing the job will travel through the stairss mentioned below:

- Constructing FEM theoretical account

- Geometry Construction

- Mesh Generation ( right component type )

- Application of Boundary and burden conditions

7.2.2 Solving

- Submiting the theoretical account to ANSYS convergent thinker

7.2.3Postprocessing

- Checking and measuring consequences

- Presentation of results- stress/strain contour secret plan, burden warp secret plans etc.

7.3Component type used in the theoretical account

The below paragraph will discourse the different component type used in the mold of beam with finite component attack.

7.3.1 Concrete ( Solid 65 )

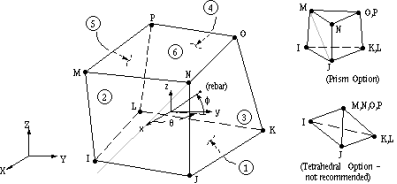

The concrete in RCC plants is straight subjected to compressive tonss, hence to pattern a beam the premier importance will be given for the stress-strain relation in compaction. For the present survey the solid 65 is taken as an component to pattern the concrete. The inside informations of the component are shown in Fig 7.1.

Fig 7.1 Solid 65 Element in ANSYS

7.3.2 Roentgeneinforcing steel( 3D spar-Link 8 )

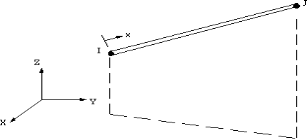

Support is modeled through nexus 8. Associate 8 is an component with three grades of freedom in x, Y, and omega waies as shown in Fig. 7.3

Fig. 7.2 Link 8 Element in ANSYS

7.4 Roentgeneal invariables

To specify the geometrical parametric quantities of embedded rebars Solid 65 component is used. The known values can be entered for stuff figure ( inside informations of support provided like top bars, underside bars and stirrups etc. ) volume ratio ( ratio of volume of steel to concrete in the component ) and orientation angles ( orientation of the support in the theoretical account ) . The package will let the user to come in three rebar stuffs in the concrete local coordinate system. The support has uniaxial stiffness and the directional orientation is defined by the user. In the present survey the beam is modeled utilizing distinct support.

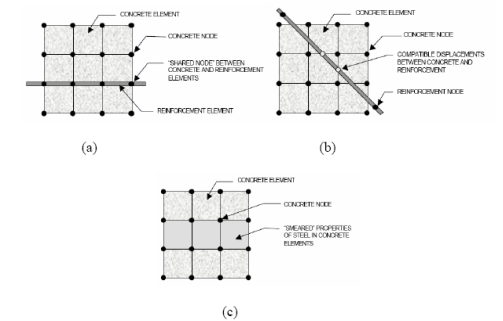

7.5 Modeling of steel support

There are three techniques to pattern steel support in strengthened concrete as shown in Fig 7.11. For the present survey, distinct mold of support is considered, since the support in the distinct theoretical account ( Fig. 7.3a ) uses beam elements. Associate 8 component is used for steel support in the beam. The theoretical account requires the, modulus of snap of steel Es as 210 GPa and Poisson’s ratio ( 0.3 ) .

Fig. 7.3 Models for Reinforcement in Reinforced Concrete ( a ) Discrete ; ( B ) Embedded ; and ( degree Celsius ) Smeared

7.6 Modeling of Crack in Concrete

The procedure of cleft formation can be divided into three phases. The uncracked phase is before the restricting tensile strength is reached. The cleft formation takes topographic point in the procedure zone of a possible cleft with diminishing tensile emphasis on cleft face due to check bridging consequence. Finally, after a complete release of the emphasis, the cleft gap continues without the emphasis.

The distinct attack is physically attractive but this attack suffers from few drawbacks, such as, it employs a uninterrupted alteration in nodal connectivity, which does non suit in the nature of finite element supplanting method ; the cleft is considered to follow a predefined way along the component borders and inordinate computational attempts are required. The 2nd attack is the smeared cleft attack. In this attack the clefts are assumed to be smeared out in a uninterrupted manner. Within the smeared construct two options are available for cleft theoretical accounts: the fixed cleft theoretical account and the revolved cleft theoretical account. In both theoretical accounts the cleft is formed when the principal emphasis exceeds the tensile strength. It is assumed that the clefts are uniformly distributed within the stuff volume. This is reflected in the constituent theoretical account by an debut of orthotropy.

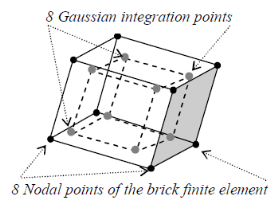

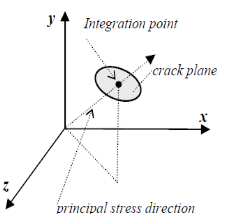

Each component has eight integrating points as shown in Fig. 7.4 at which checking and oppressing cheques are performed. The cleft formed is noted by changing the stress-strain relationships of the component to present a weak plane in the chief emphasis way.

Fig. 7.4 Gaussian Integration Points in solid 65 and Model of Crack in ANSYS

7.7Beam theoretical account in ANSYS

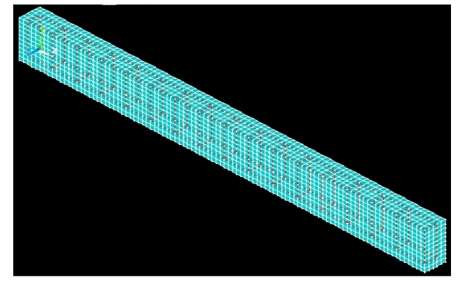

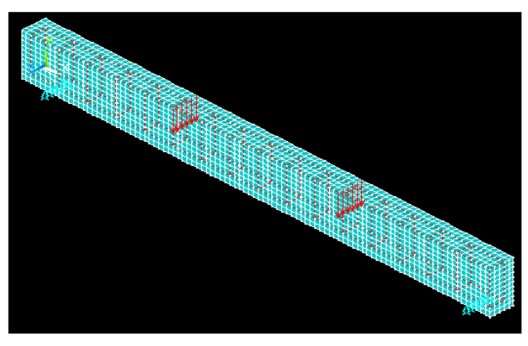

The beam was modeled with the needed parametric quantities as presented in the old subdivisions. Both type of beams ( GPC2 and OPC ) were modeled, the conventional representation of engagement, rebar agreement and application of burden on the theoretical account etc. , are as shown in Fig. 7.5 and 7.6.

Fig. 7.5 Beam theoretical account in ANSYS after engaging

Fig. 7.6 Beam theoretical account with support and application of burden

7.8Comparison of experimental consequences with ANSYS

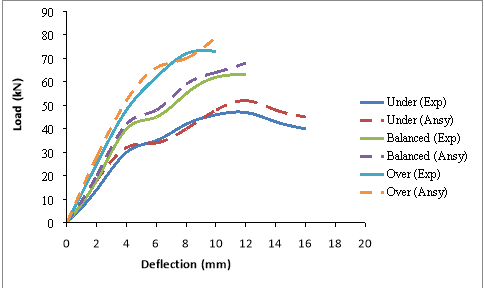

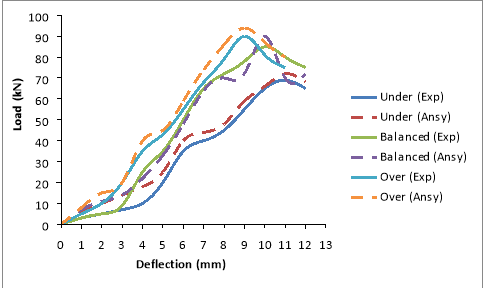

7.8.1Load warp curves

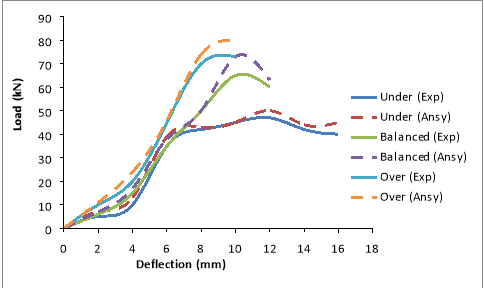

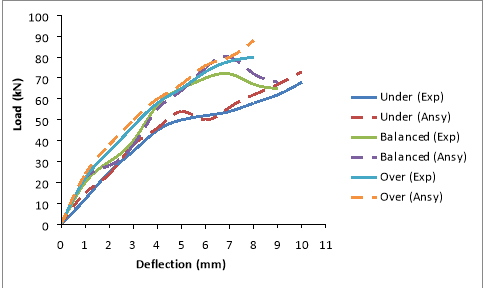

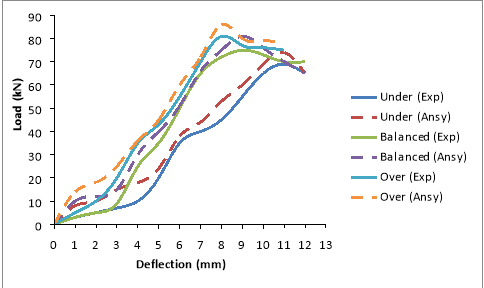

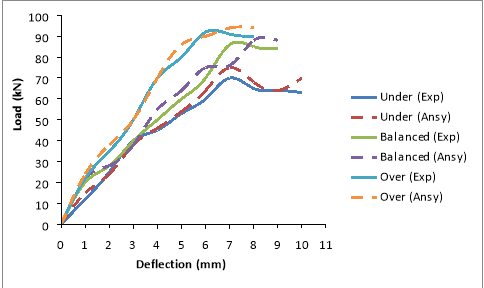

The burden warp curves obtained from the experimental probes are compared with the ANSYS consequences as presented in Table 7.1 and Fig. 7.7 to 7.12. From the information, it was observed that the analytical attack has good correlativity with the experimental values. The analytical consequences were approximately 8 to 24 % more than that of the experimental values on an norm. The scope of values was on conservative side, when visualized with first cleft burden on ANSYS. As the burden increases the tendency of consequences were in close with experimental values. This observation was true for under, balanced and over strengthened subdivisions. The alteration observed may be due to the mutual exclusiveness to account the stuff belongingss assigned in the theoretical account as compared with the experimental beam. One more ground may due to the premise done in FE analysis that the bond between the reenforcing steel and concrete is perfect, but this may non be true in existent trial beam, as we notice that there will be some sum of faux pas that has under gone when the burden on the specimen starts. The old research [ 66, 67 ] reveals with the work done for under strengthened status, the obtained consequences are in good fit with their findings.

Table 7.1 Comparison of experimental values with ANSYS consequences

|

Class of concrete |

Beam appellation |

Type of mix |

First cleft Laod ( kN ) |

Ultimate Load ( kN ) |

Deflection |

|||

|

Experimental |

ANSYS |

Experimental |

ANSYS |

Experimental |

ANSYS |

|||

|

M30 |

GPS1 |

GPC2 |

10.78 |

11 |

49 |

52 |

17 |

18.5 |

|

GPS2 |

12.6 |

13.5 |

63 |

68 |

13.4 |

14.3 |

||

|

GPS3 |

14.6 |

16 |

73 |

79 |

13 |

13.8 |

||

|

OPS1 |

OPC |

9.4 |

9.9 |

47 |

50 |

20 |

21 |

|

|

OPS2 |

13.6 |

14.2 |

68 |

73 |

17 |

18 |

||

|

OPS3 |

15.8 |

16.7 |

79 |

85 |

18 |

19 |

||

|

M40 |

GPS1 |

GPC2 |

13.4 |

14 |

67 |

73 |

17 |

18.5 |

|

GPS2 |

15.2 |

15.8 |

76 |

80 |

13.2 |

14.5 |

||

|

GPS3 |

16.4 |

17.5 |

82 |

88 |

12.8 |

14 |

||

|

OPS1 |

OPC |

13.8 |

14.3 |

69 |

74 |

16 |

17 |

|

|

OPS2 |

15 |

16 |

75 |

81 |

17 |

18 |

||

|

OPS3 |

16.2 |

17 |

81 |

86 |

18 |

19 |

||

|

M50 |

GPS1 |

GPC2 |

14 |

15 |

70 |

75 |

13 |

14 |

|

GPS2 |

17.2 |

18.4 |

86 |

93 |

13.5 |

14.5 |

||

|

GPS3 |

18.4 |

19.6 |

92 |

99 |

14 |

15 |

||

|

OPS1 |

OPC |

13.2 |

14.6 |

66 |

72 |

16 |

17 |

|

|

OPS2 |

17 |

18.5 |

85 |

91 |

16 |

16.9 |

||

|

OPS3 |

18 |

20 |

90 |

98 |

15 |

16 |

||

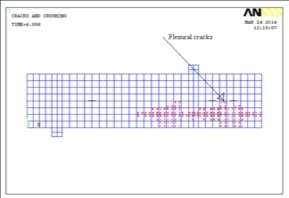

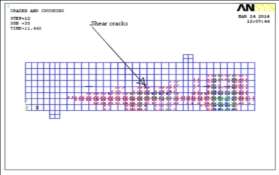

7.8.2 Failure manners and cleft forms

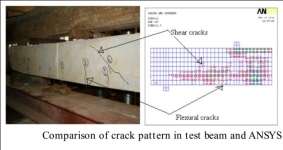

The failure manners and cleft forms are presented in Fig. 7.13 to 7.17. The outline coloring material indicated by ruddy nowadayss first cleft burden, 2nd and 3rd cleft coloring material was observed by green and bluish lineation. The first cleft burden occurred on the ANSYS theoretical account was at 20 to 22 % more than that of experimental value for about all the classs of concrete with different per centums of steel. The flexural clefts were regulating for under reinforced every bit good as balanced subdivisions as shown in Fig. 7.14 was chiefly due to flexing. The typical shear cleft was observed for over strengthened subdivision ( Fig. 7.15 ) , the cleft observed was chiefly due to higher per centum of steel, where the cleft propagated from the support. Finally the failure of sculptural beam with comparing of trial beam is presented in Fig. 7.16 and 7.17.

7.8.3 Deflection of the beam

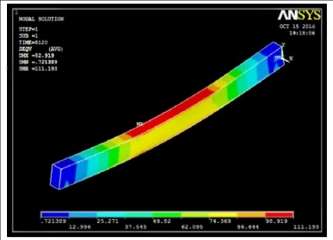

The typical warp observed in ANSYS in presented in Fig. 7.18 and 7.19. The values of warp in ANSYS were 1.3 to 9 % higher than the experimental consequences. The fringy difference in values was due to engaging of elements in the theoretical account.

Fig. 7.7 Load Vs Deflection for GPC2 beams ( M30 )

Fig. 7.8 Load Vs Deflection for OPC beams ( M30 )

Fig. 7.9 Load Vs Deflection for GPC2 beams ( M40 )

Fig. 7.10 Load Vs Deflection for OPC beams ( M40 )

Fig. 7.11 Load Vs Deflection for GPC2 beams ( M50 )

Fig. 7.12 Load Vs Deflection for OPC beams ( M50 )

Fig. 7.13 First cleft burden ( Typical )Fig. 7.14 Flexural clefts on the beam ( Typical )

Fig.7.15 Shear clefts on the beam ( Typical )Fig.7.16 Failure of beam ( Typical )

Fig.7.17 Comparison of cleft form in trial beam and ANSYS

Fig. 7.18 Deflection of the beam observed in ANSYS

7.9 Drumhead

The strengthened concrete beams ( GPC2 and OPC ) are modeled in ANSYS and the parametric quantities studied were first cleft burden, ultimate burden and warp values. The consequences obtained were validated with the bing experimental values. In most of the instances, analytical attack was on conservative side. This alteration observed may be due to the mutual exclusiveness to account the stuff belongingss assigned in the theoretical account as compared with the experimental beam. One more ground may due to the premise done in FE analysis that the bond between the reenforcing steel and concrete is perfect, but this may non be true in existent trial beam, as we notice that there will be some sum of faux pas that has under gone when the burden on the specimen starts.