Title: “Equestrian Statue of Erasmo do Narni”(Gattamelata)

Stylistic Period: 15th Century-Early Renaissance.

Bronze, height approx. 12′ 2″

Donatello’s sources for this statue were surviving Roman bronze equestrian portraits, notably the famous image of Marcus Aurelius. Which the sculptor certainly knew from his stay in Rome, as well as the famous set of Roman bronze horses installed on the façade of St. Mark’s Cathedral in Venice. Viewed from a distance, Donatello’s man-animal juggernaut, installed on a high marble base in front of the church of Sant’Antonio in Padua, seems capable of thrusting forward at the first threat. Seen up close, however, the man’s sunken cheeks, sagging jaw, ropy neck, and stern but sad expression suggest a warrior grown old and tired from the constant need for military vigilance and rapid response.

15th Century-Early Renaissance.

(Lecture Notes)

This is a sculpture that is meant for outdoors which means it is intended for public view.

It is life-size and elevated to be higher up. He is a commander of the horse. If the big mighty horse/beast responds to his commander then it means the men under his command also respond.

This sculpture is symbolic of being a greater leader.

Contemporary clothing, actual portrait. Serious because he is a leader, visually you can tell he is an intelligent, strong leader. All realistically done. NO unintentional distortion. Cast in bronze which means it was very difficult to make.

It’s a Roman version of a great emperor-Marcus Aurelius (1200 or 1300 years apart, also shown on horseback). Peace attire, Ancient Roman portraiture. 100s have been made of Ancient Roman men on horseback. Cultures destroyed art previously before them. They thought the Ancient Roman sculpture of Marcus Aurelius was Constantine so they did not destroy it.

Title: “David”

Stylistic Period: 15th-Century-Early Renaissance

Commissioned by Lorenzo de Medici for the Medici Palace. Bronze with gilded details, height 49 5/8″

15th-Century-Early Renaissance

(Lecture Notes)

Compared to Donatello’s David, Verrochio’s has a greater interest in naturalism and has done away with symbolism. This David is an adolescent but might be older than Donatello’s. Verrochio has portrayed that David used skill and intellect, but is stronger than Donatello’s.

A garment covers David’s body (upper part is molded against the body, also has a sword that matches his size), is not a Biblical garment but rather like a modern Florentine attire. The hair is also a contemporary Florentine hairstyle. Modeling David in a contemporary manner appeals to the contemporary audience.

While Donatello’s David is philosophical Verrochio has made his David cocky, proud of what he has done.

Title: Bust of a Little Boy

Stylistic Period: 15th Century-Early Renaissance

Marble.

(Lecture Notes and internet sources)

Settignao’s Bust of a Little Boy is modeled after an unknown boy presumably around 3 years of age. Sculpture was made of marble (marble was beloved in the Renaissance by sculptures b/c it was easier to carve and seems to sparkle), but it is very realistic. Has a high degree of naturalism (always beautiful and ideal). Little boy has a serious expression, but also calm.

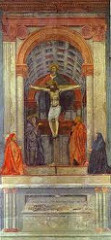

Title: “Trinity with the Virgin, St. John the Evangelist, and The Donors”

Stylistic Period: 15th Century-Early Renaissance

Fresco, 21′ x 10′ 5″

Masaccio’s fresco was meant to give the illusion of a stone funerary monument and altar table set below a deep aedicula (framed niche) in the wall. The effect of looking up into a barrel-vaulted niche was made plausible through precisely rendered linear perspective. The eye level of an adult male viewer standing within the church determined the horizon line on which the vanishing point was centered, just below the kneeling figures above the altar. And the painting demonstrates not only Masaccio’s intimate knowledge of Brunelleschi’s perspective experiments, but also his architectural style. The painted architecture is an unusual combination of Classical orders. On the wall surface, Corinthian pilasters support a plain architrave below a cornice, while inside the niche Renaissance variations on Ionic columns support framing arches at the front and rear of the barrel vault. The “source” of the consistent illumination of the architecture lies in front of the picture, casting reflections on the coffers, or sunken panels, of the ceiling.

The figures are organized in a measured progression through space. At the near end of the recessed, barrel-vaulted space is the Trinity-Jesus on the cross, the dove of the Holy Spirit poised in downward flight above his titled halo, and God the father, who stands behind to support the cross from his elevated perch on a high platform. As in many scenes of the Crucifixion, Jesus is flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist, who contemplate the scene on either side of the cross. Mary gazes calmly out at us, her raised hand drawing our attention to the Trinity. Members of the Lenzi family kneel in front of the pilasters-thus closer to us than the Crucifixion; the red robes of the male donor signify that he was a member of the governing council of Florence. Below these donors, in an open sarcophagus, is a skeleton, a grim reminder of the Christian belief that since death awaits us all, our only hope is redemption and the promise of life in the hereafter, rooted in Christ’s sacrifice on the cross. The inscription above the skeleton reads: “I was once that which you are, and what I am you also will be.”

Title: “The Tribute Money”

Stylistic Period: 15th Century-Early Renaissance

Fresco, 8′ 1″ x 19′ 7″

Symbolic- If Jesus can pay taxes then so can the Florentines. (The Florentines had just raised their taxes).

The Tribute Money is particularly remarkable for its early use of both linear and atmospheric perspective to integrate figures, architecture, and landscape into a consistent whole. Jesus, and the apostles surrounding him, form a clear central focus, from which the landscape seems to recede naturally into the far distance. To foster this illusion, Masaccio used linear perspective in the depiction of the house, and then reinforced it by demising the sizes of the distant barren trees and reducing the size of the crouching Peter at far left. The central vanishing point established by the orthogonals of the house corresponds with the head of Jesus.

The cleaning of the painting in the 1980s revealed that it was painted in 32 giornate (a giornata is a section of fresh plaster that could be prepared and painted in a single day). The cleaning also uncovered Masaccio’s subtle use of color to create atmospheric perspective in the distant landscape, where mountains fade from grayish-green to grayish-white and the houses and trees on their slopes are loosely sketched to simulate the lack of clear definition when viewing things in the distance through a haze. Green leaves were painted on the branches al secco (meaning “on the dry plastered wall”).

As in The Expulsion, Masaccio modeled the foreground figures here with bold highlights and long shadows on the ground toward the left, giving a strong sense of volumetric solidity and implying a light source at far right, as if the scene were lit by the actual window in the rear wall of the Branacci Chapel. Not only does the lighting give the forms sculptural definition; the colors vary in tone according to the strength of the illumination. Masaccio used a wide range of hues-pale pink, mauve, gold, blue-green, seafoam-green, apple-green, peach-and a sophisticated shading technique using contrasting colors, as in Andrew’s green robe which is shaded with red instead of dark green. The figures of Jesus and the apostles originally had gold-leaf haloes, several of which have flaked off. Rather than silhouette the heads against consistently flat gold circles, however, Masaccio conceived of haloes as gold disks hovering space above each head that moved with the heads as they moved, and he foreshortened them depending on the angle from which each head is seen.

Some stylistic innovations take time to by fully accepted, and Masaccio’s innovative depictions of volumetric solidity, consistent lighting, and spatial integration-though they clearly had an impact on his immediate successors-were perhaps best appreciated by a later generation of painters. Many important sixteenth-century Italian artists, including Michelangelo, studied and sketched Masaccio’s Branacci Chapel frescos, as they did Giotto’s work in the Scrovegni Chapel. In the meantime, painting in Florence after Masaccio’s death developed along somewhat different lines

Title: “Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise”

Stylistic Period: 15th Century-Early Renaissance

Fresco, 7′ x 2’11

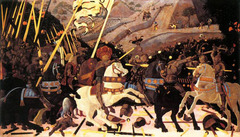

Title: “The Battle of San Romano”

Stylistic Period: 15th Century-Early Renaissance

Tempera on wood panel, approx. 6′ x 10′ 6″

An eccentric Florentine painter nicknamed Paolo Uccello (“Paul Bird”) created the panel painting. It is one of three related panels-now separated, hanging in major museums in Florence, London, and Paris-commissioned by Lionardo Bartolini Salimbeni, who led the Florentine governing Council of Ten during the war against Lucca and Siena. Uccello’s remarkable accuracy when depicting armor from the 1430s, heraldic banners, and eve fashionable fabrics and crests surely would have appealed to Lionardo’s civic pride. The hedges of oranges, roses, and pomegranates-all ancient fertility symbols-suggest that Lionardo might have commissioned the paintings at the of his wedding in 1438. Leonardo and his wife, Maddalena, had six sons, two of whom inherited the paintings.

According to a complaint brought by Damiano, one of the heirs, Lorenzo de’ Medici, the powerful de facto ruler of Florence, “forcibly removed” the paintings from Damiano’s house. They were never returned, and Uccello’s masterpieces are recorded in a 1492 inventory as hanging in the Medici palace. Perhaps Lorenzo, who was called “the Magnificent,” saw Uccello’s heroic pageant as a trophy more worhoty of a Medici merchant prince. We will certainly discover that princely patronage was a major factor in the genesis of the Italian Renaissance as it developed in Florence during the early years of the fifteenth century.

Title: “Madonna and Child with Angels”

Stylistic Period: 15th Century-Early Renaissance

Tempra on wood panel.

In this painting by Fra Filippo Lippi, Madonna and Child with Two Angels—a variation on the Madonna and Child Enthroned (see Giotto or Cimabue) that artists have been painting for hundreds of years—halos virtually disappear.

Mary’s hands are clasped in prayer, and both she and the Christ child appear lost in thought, but otherwise the figures have become so human that we almost feel as though we are looking at a portrait. The angels look especially playful, and the one in the foreground seems like he might giggle as he looks out at us.

The delicate swirls of transparent fabric that move around Mary’s face and shoulders are a new decorative element that Lippi brings to Early Renaissance painting—something that will be important to his student, Botticelli. However, the modeling of Mary’s form—from the bulk and solidity of her body to the careful folds of drapery around her lap—reveal Masaccio’s influence.

Title: “The Birth of Venus”

Stylistic Period: 15th Century-Early Renaissance

Tempera and gold on canvas, 5′ 8 7/8″ x 9′ 1 7/8″

Botticelli returned to Florence that same year and and entered a new phase of his career. Like other artists working for patrons steeped in Classical scholarship and humanistic thoughts, he was exposed to philosophical speculations on beauty-as well as to the examples of ancient art in his employers’ collections. For the Medici, Botticelli produced secular paintings of mythological subjects inspired by ancient works and by contemporary Neoplatonic thought. Art historian Micheal Baxandall has shown that these works were also patterned on the slow movements of fifteenth-century Florentine dance, in which figures acted out their relationships to one another in public performances that would have influenced the thinking and viewing habits of both painters and their audience.

Several years after the Primavera, some of the same mythological figures reappeared in Botticelli’s BIRTH OF VENUS, in which the central image represents the Neoplatonic idea of divine love in the form of a nude Venus based on an antique statue type known as the “modest venus” that ultimately derives from Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos. Botticelli’s Classical goddess of love and beauty, born of sea foam, averts her eyes from our gaze as she floats ashore on a scallop shel, carefully arranging her hands and hair to hide-but actually drawing attention to-her sexuality. Indeed, she is an arrestingly alluring figure, set within a graceful composition organized by Botticelli’s characteristically decorative, almost calligraphic use of line. Blown by the wind-Zephyr (with his love, the nymph Chloris)-Venus arrives at her earthly home. She is welcomed by a devotee who offers her a garment embroidered with flowers. The circumstances of this commission are uncertain. It is painted n canvas, which suggests that it may have been a banner or a painted tapestrylike wall hanging.

Title: “Battista Sforza and Federico da Montefeltro”

Stylistic Period: 15th Century-Early Renaissance

Oil on wood panel, each 18 1/2″ x 13″

Title: “Interior and Ceiling of the Painted Chamber”

Stylistic Period: 15th Century-Early Renaissance

Fresco, room 26′ 6″ square

Perhaps his finest works are the frescos of the CAMERA PICTA (“Painted Room”), a tower chamber in Ludovico’s palace, which Mantegna decorated between 1465 and 1474. Around the walls the family-each member seemingly identified by a portrait likeness-receives in landscapes and in loggias the return of Ludovico’s son, Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga.

Title: “Interior and Ceiling of the Painted Chamber”

Stylistic Period: 15th Century-Early Renaissance

Fresco, diameter of false oculus 8′ 9″

Title: “Portrait of a Man and Boy”

Stylistic Period: 15th Century-Early Renaissance

The sixteenth century was an age of social, intellectual, and religious ferment that transformed European culture. It was marked by continual warfare triggered by the expansionist ambitions of warring rulers. The humanism of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, with its medieval roots and its often uncritical acceptance of the authority of Classical texts, slowly developed into a critical exploration of new ideas, the natural world, and distant lands. Cartographers began to acknowledge the Earth’s curvature and the degrees of distance, giving Europeans a more accurate understanding of their place within the world. The printing press sparked an explosion in book production, spreading new ideas through the translation and publication of ancient and contemporary texts, broadening the horizons of educated Europeans and encouraging the development of literacy. Since travel was growing more common, artists and their work became mobile, and the world of art was transformed into a more international community.

At the start of the sixteenth century, England, France, and Portugal were nation-states under strong monarchs. German-speaking central Europe was divided into dozens of principalities, counties, free cities, and small territories. But even states as powerful as Saxony and Bavaria acknowledged the supremacy of the Habsburg Holy Roman Empire-in theory the greatest power in Europe. Charles V, elected emperor in 1519, also inherited Spain, the Netherlands, and vast territories in the Americas. Italy, which was divided into numerous small states, was a diplomatic and military battlefield where, for much of the century, the Italian city-states, Habsburg Spain, France, and the papacy fought each other in shifting alliances. Popes behaved like secular princes, using diplomacy and military force to regain control over central Italy and in some cases to establish family members as hereditary rulers.

The popes’ incessant demands for money, to finance the rebuilding of St. Peter’s as well as their self-aggrandizing art projects and luxurious lifestyles, aggravated the religious dissent that had long been developing, especially in the north of the Alps. Early in the century, religious reformers within the established Church challenged beliefs and practices, especially Julius II’s sale of indulgences promising forgiveness of sins and assurance of salvation in exchange for a financial contribution to the Church. Because they protested, these northern European reformers came to be called Protestants; their demand for reform gave rise to a movement called the Reformation.

The political maneuvering of Pope Clement VII (pontificate 1523-1434) led to a direct clash with Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. In May 1527, Charles’s troops attacked Rome, beginning a six-month orgy of killing, looting, and burning. The Sack of Rome, as it is called, shook the sense of stability and humanistic confidence that until then had characterized the Renaissance, and it sent many artists fleeing from the ruined city. Nevertheless, Charles saw himself as the leader of the Catholic forces-and he was the sole Catholic ally Clement had at the time. In 1530, Clement VII crowned Charles emperor in Bologna.

Sixteenth-century patrons valued artists highly and rewarded them well, not only with generous commissions but sometimes even high social status. Charles V, for example, knighted the painter Titian. Some painters and sculptors became entrepreneurs and celebrities, selling prints of their works on the side and creating international reputations for themselves. Many artists recorded their activities-professional and private-in diaries, notebooks, and letters that have come down to us. In addition, contemporary writers began to report on the lives of artists, documenting their physical appearance and assessing their individual reputations. In 1550, Giorgio Vasari wrote the first survey of Italian art history (revised and expanded in 1568)-Lives of the Most Excellent Architects, Painters, and Sculptors-organized as a series of critical biographies but at its core a work of critical judgement. Vasari also commented on the role of patrons, and argued that art had become more realistic and more beautiful over time, reaching its apex of perfection in his own age. From his characterization developed our notion of this period as the High Renaissance-that is, as a high point in art since the early experiments of Cimabue and Giotto, marked by a balanced synthesis of Classical ideals and a lifelike rendering of the natural world.

During this period, the fifteenth-century humanists’ notion of painting, sculpture, and architecture not as manual arts but as liberal (intellectual) arts, requiring education in the Classics and mathematics as well as in the techniques of the craft, became a topic of intense interest. And from these discussions arose the Renaissance formulation-still with us today-of artists divinely inspired creative geniuses, a step above most of us in their gifts of hand and mind. This idea weaves its way through Vasari’s work like an organizing principle. And this newly elevated status to which artists aspired favored men. Although few artists of either sex had access to the humanist education required by the sophisticated, often esoteric, subject matter used in paintings (usually devised by someone other than the artist), women were denied even the studio practice necessary to study and draw from nude models. Furthermore, it was almost impossible for an artist to achieve international status without traveling extensively and frequently relocating to follow commissions-something most women could not do. Still, some European women managed to follow their gifts and establish careers as artists during this period despite the obstacles that blocked their entrance into the profession.

Title: “The Last Supper”

Stylistic Period: 16th Century-High Renaissance

Tempera and oil on plaster, 15′ 2″ x 28′ 10″

At Duke Ludovico Sforza’s request, Leonardo painted THE LAST SUPPER in the refectory, or dining hall, of the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan between 1495 and 1498. In fictive space defined by a coffered ceiling and four pairs of tapestries that seem to extend the refectory itself into another room, Jesus and his disciples are seated at a long table placed parallel to the picture plane and to the monastic diners who would have been seated in the hall below. In a sense, Jesus’ meal with his disciples prefigures the daily gathering of this local monastic community at mealtimes. The stagelike space recedes from the tape to three windows on the back wall, where the vanishing point of the one-point linear perspective lies behind Jesus’ head. A stable, pyramidal Jesus at the center is flanked by 12 disciples, grouped in four interlocking sets of three.

On one level, Leonardo has painted a scene from a story- one that captures the individual reactions of the apostles to Jesus’ announcement that one of them will betray him. Leonardo was an acute observer of human behavior, and his art captures human emotions with compelling immediacy. On another level, The Last Supper is a symbolic evocation of Jesus’ coming sacrifice for the salvation of humankind, the foundation of the institution of the Mass. Breaking with traditional representations of the subject to create compositional clarity, balance, and cohesion, Leonardo placed the traitor Judas-cluthcing his money bags in the shadows-within the first triad to Jesus’ right, along with the young John the Evangelist and the elderly Peter, rather than isolating Judas on the opposite side of the table. Judas, Peter, and John were each to play an essential role in Jesus’ mission: Judas set in motion the events leading to Jesus’ sacrifice; Peter led the Church after Jesus’ death; and John, the visionary, foretold the Second Coming and the Last Judgement in the Book of Revelation.

The painting’s careful geometry, the convergence of its perspective lines, the stability of its pyramidal forms, and Jesus’ calm demeanor at the mathematical center of all the commotion, work together to reinforce the sense of gravity, balance, and order. The clarity and stability of this painting epitomize High Renaissance style.

Title: “Mona Lisa”

Stylistic Period: 16th Century-High Renaissance

Oil on wood panel, 30 1/4″ x 21″

A fiercely debated topic in Renaissance Italy was the question of the relative merits of painting and sculpture. Leonardo insisted on the supremacy of painting as the best and most complete means of creating an illusion of the natural world, while Michelangelo argued for sculpture. Yet in creating a painted illusion, Leonardo considered color to be secondary to the depiction of sculptural volume, which he achieved through his virtuosity in sfumato. He also unified his compositions by covering them with a thin, lightly tinted varnish, which enhanced the overall smoky haze. Because early evening light tends to produce a similar effect naturally, Leonardo considered dusk the finest time of day and recommended that painters set up their studios in a courtyard with black walls and a linen sheet stretched overhead to reproduce twilight.

Leonardo’s fame as an artist is based on only a few works, for his many interests took him away from painting. Unlike his humanistic contemporaries, he was not particularly interested in Classical literature or archaeology. Instead, his passions were mathematics, engineering, and the natural world. He complied volumes of detailed drawings and notes on anatomy, botany, geology, metrology, architectural, design, and mechanics. In his drawings of human figures, he sought not only the precise details of anatomy but also the geometric basis of perfect proportions. Leonard’s searching mind is evident in his drawings, not only of natural objects and human beings, but also of machines, so clearly and completely worked out that modern engineers have used them to construct working models. He designed flying machines, a kind of automobile, a parachute, and all sorts of military equipment, including a mobile fortress. His imagination outran his means to bring his creations into being. For one thing, he lacked a source of power other than men and horses. For another, he may have lacked focus and follow-through. His contemporaries complained that he never anything and that his inventions distracted from his painting.

Leonardo returned to Milan in 1508 and lived there until 1513. He also lived for a time in the Vatican at the invitation of Pope Leo X, but there is no evidence that he produced any works of art during his stay. In 1516, he accepted the French king Francis I’s invitation to relocate to France as an adviser on architecture, taking the Mona Lisa, as well as other important works, with him. He remained at Francis’s court until his death in 1519.

Title: “Philosophy”(School of Athens)

Stylistic Period: 16th Century-High Renaissance

Fresco

SIDE NOTE:

Plato is pointing to the heavens, Aristotle is pointing to the earth.

Raphael achieved a lofty style in keeping with papal ambition-using ideals of Classical grandeur, professing faith in human rationality and perfectibility, and celebrating the power of the pope as God’s earthly administrator. But when Raphael died at age 37 on April 6, 1520, the grand moment was already passing: Luther and Protestant Reformation were challenging papal authority and the world would never be the same again.

Raphael left Florence about 1508 for Rome, where Pope Julius II put him to work almost immediately decorating rooms (stance, singular stanza) in the papal apartments. In the Stanza della Segnatura-the Pope’s private library-Raphael painted the four branches of knowledge as conceived in the sixteenth century: Religion (the Disputà, depicting discussions concerning the true presence of Christ in the Eucharistic Host), Philosophy (The School of Athens), Poetry (Parnassus, home of the Muses), and Law (the Cardinal Virtues under Justice).

Raphael’s most influential achievement in the papal rooms was The School of Athens, painted about 1510-1511. Here, the painter seems to summarize the ideals of Renaissance papacy in a grand conception of harmoniously arranged forms in a rational space, as well as in the calm dignity of the figures that occupy it.

Title: “Baldassare Castiglione”

Stylistic Period: 16th Century-High Renaissance

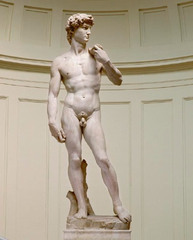

Title: “David”

Stylistic Period: 16th Century-High Renaissance

Marble, height 17′ feet tall without pedestal.

Title: “Sistine Chapel Ceiling”

Stylistic Period: 16th Century-High Renaissance

Michelangelo considered himself a sculptor, but the strong-minded pope wanted paintings; work began in 1508. Michelangelo complained bitterly in a sonnet to a friend: “This miserable job has given me a goiter….the force of it has jammed my belly up beneath my chin. Beard to the sky…Brush splattering make a pavement of my face…I’m not a painter.” Despite his physical misery as he stood on a scaffold, painting the ceiling just above him, the results were extraordinary, and Michelangelo established a new and remarkably powerful style in Renaissance painting.

Julius’s initial order for the ceiling was simple: trompe l’oeil coffers to replace the original star-spangled blue decoration. Later he wanted the 12 apostles seated on thrones on the triangular spandrels between the lunettes framing the windows. According to Michelangelo, when he objected to the limitations of Juliu’s plan, the pope told him to paint whatever he liked. This Michelangelo presumably did, although he was certainly guided by a theological advisor and his plan no doubt required the pope’s approval.

In Michelangelo’s design, an illusionistic marble architecture establishes a framework for the figures and narrative scenes on the vault of the chapel. Running completely around the ceiling is a painted cornice with projections supported by pilasters decorated with “sculptured” putti. Between the pilasters are figures of prophets and sibyls (female seers from the Classical world) who were believed to have foretold Jesus’ birth. Seated on the fictive cornice are heroic figures of nude young men called ignudo), holding sashes attached to large gold medallions. Rising behind the ignudi, shallow bands of citive stone span the center of the ceiling and divide it into nine compartments containing successive scenes from Genesis-recounting the Creation, the Fall, and the Flood-beginning over the altar and ending near the chapel entrance. God’s earliest acts of creation are therefore closest to the altar, the Creation of Eve at the center of the ceiling, followed by the imperfect actions of humanity: Temptation, Fall, Expulsion from Paradise, and God’s eventual destruction of all people except Noah and his family by the Flood. The eight triangular spandrels over the windows, as well as the lunettes crowning them, contain paintings of the ancestors of Jesus.

Title: “The Creation of Adam”

Stylistic Period: 16th Century-High Renaissance

Fresco. 9′ 2″ x 18′ 8″

Title: “Last Judgement”

Stylistic Period: 16th Century-High Renaissance

Fresco, 48′ x 44′

The Last Judgement was a common theme in church art, but Michelangelo’s interpretation was entirely novel. His vision of the Apocalypse is a swirling maelstrom, filled with thick-set and muscular naked figures. Traditional symmetry and order are replaced by dynamic,often violent, action, in which the rules of perspective and proportion are suspended. The painting speaks directly about the salvation of souls—an issue which was widely debated in this period of religious upheaval.

Although Michelangelo took great care to strip the nude figures of their sensuality, the Last Judgement still caused offense to some members of the church. After his death in 1564 there were calls for it to be censored, largely because so many prints of the painting were circulating. As a result, Michelangelo’s friend Daniele da Volterra painted drapery on some of the figures.

Ex. Masaccio made the “Trinity with the Virgin, St. John the Evangelist, and Donors” appear as if were a real chapel and not a fresco on a wall.

Ex. Leonardo’s Mona Lisa and other works by Leonardo