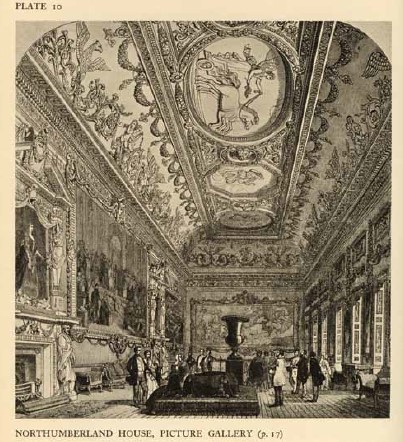

In the 1750s, Hugh Smithson, recently created Earl of Northumberland, added an immense gallery to Northumberland House, his London town house at Charing Cross and the Strand (later Trafalgar Square). The gallery was decorated with huge painted copies after frescos by Raphael, Annibale Carracci and Guido Reni (Fig. 6.1). Less than a decade later, the Earl commissioned Robert Adam to renovate Syon House, his Middlesex country retreat, and embellish it with numerous copies and casts of iconic classical sculpture. While the painted and sculpted replicas have been discussed separately in detail by different authors, I would like to study both together in order to emphasise the role of painted copies and sculptural casts and copies as an expression of aristocratic patronage in the mid eighteenth century and in the formation of a ‘Grand Manner’ of art.

Smithson’s building schemes tell us much about his consciousness of status in a society which was, by the middle of the century, defined by the Shaftesburian concept of natural aristocracy that embraced a balanced commingling of erudition and civic duty. Smithson was from modest gentry stock but, as an assiduous place-hunter, quickly climbed the patriciate ladder through fortuitous inheritances, marriage and political acuity. Brought up a Roman Catholic, he ‘conformed’ after his father’s death in the 1720s, although he remained a Tory in opposition to Robert Walpole until after the Jacobite rout in the 1740s when he sensibly became a soft Whig in the Newcastle–Pelhamite broad-bottom coalition. However, he forsook any real party allegiance, opting instead to stay close to the Hanoverian court, serving as Lord of the Bedchamber to George II and receiving the Order of the Garter in 1756. He later allied himself to George III and the Earl of Bute (his son married Bute’s daughter) with varying consequences through the turbulent factious decade of the 1760s.

Exemplum – the demonstration of one’s virtue – is a critical feature of the Shaftesburian concept of the aristocrat, and material culture, in the form of architecture, a good library, collections of paintings, prints, coins and medals, along with proper dress and fine dining, was a means to an end.

Perhaps compensating for his quasi-parvenu and Catholic-Tory heritage, Northumberland was overly zealous, evidenced by his penchant for scale. At Northumberland House, the gallery, which could easily accommodate six hundred people, measured 106 feet long and each of the paintings was immense. Similarly Syon House, despite its comparatively modest size, evokes a sense of massive ponderousness in the entrance hall, while the apparent narrowness of the library on the other side of the house illusionistically accentuates its great length. Yet Northumberland’s endeavours were rescued from mere ostentation by their inherent dignity and refinement.

The Northumberland House gallery, designed by Daniel Garrett and then James Paine with the Earl’s involvement, had an overall decorative programme of stucco, painting and sculpture reminiscent of the galleries of Roman Renaissance and Baroque palaces that the Earl would have seen on his grand tour in the 1730s. For the painted copies, the Earl employed Horace Mann as agent, specifying copies after ‘Raphael, Guido or Carracci’ from ‘the Farnese gallery or the Vatican’ and ultimately approving of the choices that Mann had made. Cardinal Albani also played a critical role as he assisted Mann in securing access to the original frescos and in negotiating with the artists.

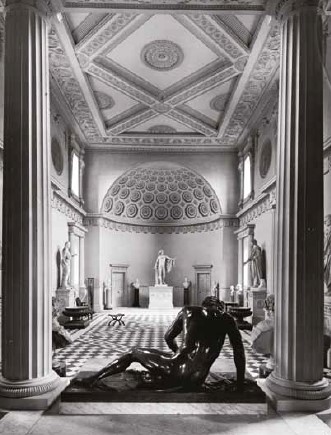

The final selection consisted of Raphael’s Council of the Gods and Marriage of Cupid and Psyche from the Villa Farnesina, both by Pompeo Batoni, who was dilatory in completing the commission; Annibale Carracci’s Bacchus and Ariadne from the Palazzo Farnese, by Placido Costanzi; Guido Reni’s Aurora from the Villa Rospigliosi, by Agostino Masucci; and Raphael’s School of Athens by Anton Raphael Mengs (Mengs was simultaneously working on his painting of Parnassus for the Villa Albani). Simon Vierpyl was also hired to make modelli based on the sculptures of the Barbarian captives at the Capitoline which were then fashioned into two chimneypieces by Benjamin Carter. These, in turn, were surmounted by full-length portraits of the Earl and his wife, Elizabeth Seymour, by Joshua Reynolds.7 At Syon House, Adam, with the assistance of his brother, James, and with the approbation of the Earl, fashioned the entrance hall after that of an ancient Roman villa suburbana which would have typically been embellished with busts of the owner’s ancestors (Fig. 6.2). However, in place of the Earl’s less than salubrious forebears, the hall was furnished with statues and busts, including Demosthenes, Socrates, Antisthenes, Marcus Aurelius, Scipio Africanus and Livia, as well as Roman noblemen and noblewomen.

It was also bounded at either end by a plaster cast of the Apollo Belvedere and a bronze copy of the Dying Gaul by Luigi Valadier. The exquisite dark patina of the bronze contrasts with the other white sculptures and the rest of the room. The visitor is drawn up to the anteroom, an explosion of polychrome with twelve verde antico columns, eight of which support gilt casts of the Venus de’Medici, the Callipygian Venus, the Celestial Venus, the Mercury, the Dancing Faun, the Idolino, the Belvedere Antinous and one more (later replaced by a cast of Canova’s Hebe). Bronze casts of the Belvedere Antinous and the Borghese Silenus with the Infant Bacchus reside in niches (Fig. 6.3). In the adjacent, more visually neutral, dining room, white marble copies of the Apollino, the Diane Chasseresse from Versailles, the Flora from the Capitoline and Euterpe, the muse of music, are positioned in niches on one wall with a statue of Ceres by Bartolomeo Cavaceppi and a marble copy, by Joseph Wilton, of Michelangelo’s Bacchus from the cast Wilton had made for the Duke of Richmond’s Gallery at Richmond House, Whitehall (Fig. 6.4).

At both houses, a combination of size, composition and subject matter determined the final selection. In the Northumberland House gallery, four of the five paintings – the School of Athens being the exception – form strong horizontals crowded with classical deities in various states of déshabillé. While the degree of undress did not match the sartorial abundance of the London bon ton (yet was no doubt appealing and arousing for many), the flowing draperies in the paintings, combined with the densely populated and animated compositions, would have been in step with the swirling multitudes who attended Northumberland’s sumptuous assemblies. A copy of the equally energetic Battle of Constantine in the Vatican, thought in the eighteenth century to be by Giulio Romano, was to have completed the ensemble. However, the size and proportions of the original fresco did not correspond easily with the dimensions of the gallery wall available so the idea was rejected by Mann. Albani, evidently misreading the tone that Northumberland wished to set, suggested replacing the Battle of Constantine and another fresco with Giulio Romano’s two Feasts of the Gods from the Sala di Psiche in the Palazzo del Tè, Mantua. Mann, Albani and Northumberland ultimately settled on the School of Athens, which Mengs had already been studying for a number of years. The more philosophical content cast a rather heavy note of erudite profundity across the gallery but one that none the less would have reflected well on the owner.

The portrayal of Michelangelo/Heraclitus leaning against a block of marble and wearing sixteenth-century stone cutter’s dress may also have amused Northumberland who had served as Master of a Masonic Lodge in Florence in the 1730s.10 Although it is not known if Northumberland continued to be a Mason once he returned from the Continent, by 1736 he had become a Fellow of the Royal Society and Society of Antiquaries as well as a member of the Society of Dilettanti, all fraternities of the erudite as well as haunts of Freemasons. Furthermore, the dignified composition of the School of Athens, like the portraits of the Duke and Duchess, paced and punctuated the space of the gallery, in contrast to the highly energetic, mythological subject matter of the other paintings.

The tone at Syon House, meanwhile, was more reserved; the serene gravitas of the entrance hall leading to the anteroom and dining room exuded genteel leisure.Syon House and Kedleston Hall in Derbyshire, rebuilt by Nathaniel Curzon, are usually paired in scholarly discussion since they were two of Robert Adam’s earliest commissions upon his return from Italy. Like Northumberland, Curzon built in the latest au courant style; he first employed Matthew Brettingham, then James Paine and finally the much more suave and savvy Adam who, in contrast to Brettingham and Paine, had been careful to hone his professional skills to cultivate potentialpatrons. The great showpieces of Kedleston are the marble hall and saloon for which the Roman villa courtyard and the Pantheon serve as prototypes. Both are also filled with plaster casts of iconic aesthetic statues set within niches along the walls and, in the hall, behind a screen of alabaster columns .

Each of the rooms at Kedleston and Syon functions as a totality, in which sculpture, architecture, paintings and furniture create a holistic decorative environment. However, the visitor’s viewing experience and engagement with the space in the two houses are markedly different. The marble hall and the saloon at Kedleston can be viewed ‘at a glance,’ as Peter de Bolla has noted, where the look is ‘relaxed’ and ‘the eye flits from surface to surface, delighting in the variety of decoration, the sheen and glitter of the reflective surfaces’. The individual components do not demand discrete attention but rather meld into an overall whole. This is consistent with Adam’s personal, more picturesque approach to architectural design. The pictorial sweep is also reinforced by the ambiguous nature of the marble hall and the saloon; they seem to be spaces that are to be admired first and then perhaps used. In contrast, the sculptures in the entrance hall at Syon retain their individuality, and are physically accentuated by being mounted on pedestals within the space of the room rather than demurely residing in niches along the walls.

Similarly, the various components of the architecture revel in their individual robustness. As such, the entrance hall at Syon is emphatically more Bramantesque in spirit, in the sense that each component retains its integrity yet also contributes to a unified harmonious whole. Although perhaps more fortuitous than planned, given the late addition of the School of Athens, the gallery at Northumberland House is imbued with the same aesthetic; the paintings and chimneypieces contribute to a cohesive whole, yet each stands alone in its own right. Furthermore, both the entrance hall at Syon and the gallery at Northumberland House are also emphatically functional ‘lived-in’ spaces; the visitor experiences them rather than merely looks at them. The anteroom and dining room at Syon are closer to the typical ‘Adamesque’ pictorial interior, but even here the individual components of column and statue each retain their robust integrity and the visitor becomes absorbed into the space; the function of each room is always explicit. The contrasting visitor experience at Syon and Kedleston was dictated by the patrons’ different agendas. Curzon, soon to be First Baron Scarsdale, was, like Northumberland, acutely aware of the requisite ingredients of the natural aristocracy, with the exemplary country house being of the greatest significance.

However, being a generation younger than Northumberland, he was a decade behind in cutting his political teeth and staking his claim to gentry status. By the 1760s, when he was rebuilding Kedleston, the country house could be used for political gain. Wentworth Woodhouse, for example, owned by the marquises of Rockingham, encapsulates the shift in the perception of the country house as the natural expression of the natural aristocracy to something more politically innervated. At midcentury, the Second Marquis, as a young man, took on the task of completing the house begun by his father, the First Marquis, in the 1720s. This included acquiring casts and copies of iconic antique sculptures for the two main entrance halls. By the 1760s, the house and estate took on greater political import as Rockingham became the leader of the eponymous Rockingham Whigs (the antecedent of the modern concept of political party), whose central tenet was the reification of the natural aristocracy as England’s natural leaders, in the face of the rising career politician and the interventions of the King and Lord Bute. In this sense, Wentworth Woodhouse became Rockingham’s political power base and the literal physical manifestation of the Rockinghamite ‘natural family mansion’, a concept formed and espoused by Edmund Burke, Rockingham’s private secretary.15 Seen in this light, Kedleston could be read, as Mark Girouard has posited, as Curzon’s Tory riposte to nearby Chatsworth, a perennial Whig stronghold.16 As such, it could be argued that Kedleston revels more in mere display than in the exemplum of virtue, an exhibition of the accoutrements of aristocracy rather than a demonstration of personal family substance and motivation toward inspiration. Curzon, who had notably not made the Grand Tour, seems to have opted for the package deal, leaving much of the design and the selection of sculpture to first Brettingham, then Paine and Adam. Northumberland was preoccupied with other concerns; he had taken the apolitical path of siding with the monarchy and had spent much money and many years shoring up his familial legitimacy.