2: both have high level of asymmetry but the later one brought in more elements to add to the harmonious tension

3: both have the use of vanishing point to create perspective but the later one have a deeper dimension due to the changes in proportion

4: both have a correspondence between the left part and the right but in the left there are alternations of front and back but the right one only has a frontal view

5: light comes form different sides of the painting (may have something to do where the painting is placed in the church)

6: flipped composition and Maria’s face is lit in both images

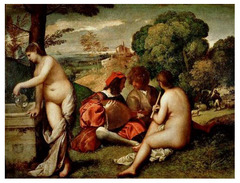

7: both have atmospherical perspective misty backgrounds

8: the proximity between the figures create an engagement within the scene

9: In Raphael’s painting the Virgin’s right arm goes across the center of the scene to draw attention to the ring arm and hand: subject matter

10: In Raphael’s painting there is an extensive use of fundamental circle and as the result the harmony of the proportion is consciously achieved.

11: They both have a very important vertical axis but Raphael intentionally makes his axis go right between Joseph and Mary’s fingers. The Immediate tension thus is created.

Competition Panel: Sacrifice of Issac (1401-1403)

2: The dramatic tension is immediate

3: The servants are separated from the center of the scene by a horizontal rocky bar

4: not so much scenery

5: quatrefoil

6: the servant at the left bottom of the scene is probably inspired by Spinario

7: consists of several separately cast parts

8: In his trail relief Brunelleschi organized the forms to focus on the dynamic figure of Abraham whose arm, lifted to strike Issac, is grasped by the angel rushing in from the left;

9: Issac, contorting his posture, struggling, increased the drama;

10: Great Naturalism and Great Drama

competition panel: Sacrifice of Issac(1401-1403)

2: it is less dramatic, milder and more elegant

3: The servants are separated by an integral rock that goes through the whole image and while separating also unifies the whole picture with an elegant land scape that is reminiscent of classical creation

4: more detailed and fluent modeling and casting. as one piece

5: quatrefoil

6: something important to notice: the artist is supposed to fill the four lobes of the quatrefoil while conveying the narrative succinctly and naturalistically.

7: Better in composition, rendering of the human form, and observation of natural details: technical Fineness

8: Ghiberti solved the problem of the quatrefoil field by placing narrative details in the margins and the focal point at the center;

9: great contrast between Issac’s nudity and his father’s drapery;

10: Ghiberti’s composition successively combines movement, focus, and narrative;

11: His interest in the Lyrical patterning of the the International Gothic Tempers the brutality of the scene.

12: Abraham’s drapery falls in cascades similar to those of the figure of Moses in Sluter’s The Well of Moses

The Well of Moses

North Doors of the Florence Baptistry (1403-1424)

East Doors of the Florence Baptistry (1425-1452)

2: continuous narrative

Story of Jacob and Esau (1435)

2: detail: Issac touching the neck of Jacob which is covered in goat skin

3: Maids’ drapery has fluent curves and folds that is similar to that of Antiquity, eg. Hellenistic drapery

4: This also shows Ghiberti’s preference for elegant mild scenes

5: the use of Schiacciato

6: The graceful proportions, elegant stances, and fluid drapery of the figures bespeak Ghiberti’s allegiance to the International Gothic Style;

7: The hint of depth seen in The Sacrifice of Isaac has grown in here into a deeper space defined by the arches of a building planned to accommodate the figures as they appear and reappear throughout the structure in a continuous narrative

8: Ghiberti’s spacious hall is a fine example of Early Renaissance architectural design

South Doors of the Florence Baptistry (1330-1336)

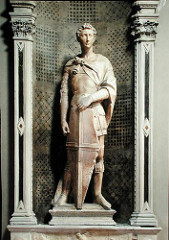

St. George (1410-1417)

Or

St Michele

Florence

2: half-turned pose:haughty look

3: maybe holding a bronze sword and wearing a bronze helmet

4: Donatello was one of the first people who pours psychological individuality and human mentality into the work

5: shallow niche makes the figure about to step out of it, thus even tho dressed in armor, he appears able to move his body easily

6: His stance, with the weight placed on the forward leg, suggests he is ready for combat;

7: The controlled energy is reflected in his eyes, which seem to scan the horizon for the enemy;

8: Portrayed as a Christian soldier;

9: Here on the relief Donatello devised a new form of shallow relief called Schiacciato, meaning flattened-out, yet he created an illusion of almost infinite depth.

10: In this relief, the landscape behind the figures consists of delicate surface modulations that catch light from varying angles;

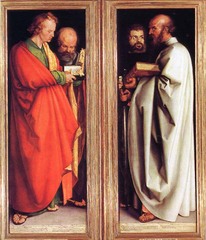

Four Martyr Saints (1409-1406/7)

Or

St. Michele

Florence

2: fleshy and realistic body shown through the drapery

3: toga-statue revived

4: more freedom than the jamb figures on Chartres

5: contrapposto

6: Their bodies seem to spill out of the confines of the niche, draped as they are in the heavy folds of their togas

7: The drapery and the heads of the second and third of the Coronati directly recall Roman Portrait sculpture of the first century CE

8: It was as if Nanni was were situating the martyrs in their historical moment, and his figures emulate Roman verism and monumentality;

9: The relief below the saints represents a sculptor, stonecutters, and a mason at work, both explaining the story of the martyrs and advertising the skills of the patrons who commissioned the work. This double function occurs often in the statues designed for the niches on San Michele, reflecting the building’s double origin in commerce and piety.

David, early 1420s-60s

*:sinuous s-curved contrapposto

*: slight smile with provocative charm

*: As Martin Kemp points out, David served as a civic role model-as a youth who rejected the armor offered to him and went to battle naked, and his victory is hence all the more remarkable for the contrast between the victor and his far more formidable foe. According to this view, David’s apparently classicizing nudity might also have narrative importance.

*: shows Donatello’s wide range of subject matter, imagination and artistic flexibility and high expertise in deploying technical media.

*David may have served as a symbol for the florentine pride and belief in their victory over the enemy, themselves as God’s chosen defender of fate: idealistic analogy

*: nudity is used here a reflection of a divine idea, since man is based on the image of God himself

*: and David’s identity as a Biblical figure justifies his nudity: not Pagan

*: a work of daring that shows Donatello’s pioneering in discovering imagery power conveyed in new forms and methods

*: the feather that goes all the way up his thigh adds to the erotism of the sculpture

*: the david may be the first free-standing , life size nude statue made since antiquity

*: The broad-brimmed hat and knee-high boots seem to accentuate his nudity

The Virgin and Child at the fountain

*: Yet van Eyck includes a rendering of a fountain of astonishing verisimilitude , the more so because of its tiny dimensions.

*: Designed maybe for private devotion

*:

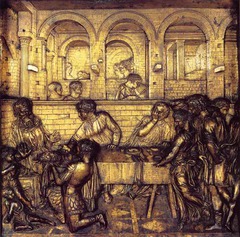

Feast of Herod

Baptistry of Siena, c, 1425

*: the roughness of the image conveys a sense of rapid motion and movement that is going to turn into a surprising violence

*: The gourmet of Salome indicates that was the end of her dance that is going to be followed by the execution and utter horror of the recoiling Herod,

*: The image consists of a complex architectural space that sets the background for a continuous narrative made of several stages of the development of the story

*: full of urgency and immediacy

*: again reflects Donatello’s mastery of a wide range of artistic styles

Gattamelata

Padua, 1445-1450

*: proud forwarding calvary culture different form the commanding solemnity of roman emperor Marcus Aurealius, which provides an uninterrupted heritage since antiquity

*: the use of repetitive curves and arches used brings a series of curvilinear lines echoing with each other

*haughty masculinity: holding the horse back and commanding: military figure

St. Mary Magdalen

1430-1450

*: the long thin sullen and withered texture of the media speaks for its subject matter

*: details such as missing teeth, hollow cheek, deep shadowed eyes all speak for the intensive religious nature of her and the harshness of life in the wild

*: this theme is a revolutionary select and use of subject

Madonna and child

Or San Michele, Florence

1465

* Brunelleschi Arch flanked by lilies

* The blue background highlights the flowers and the architectural forms

* eye contact between Mary& Child and the viewers

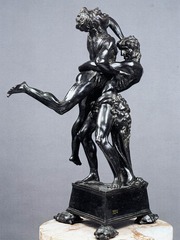

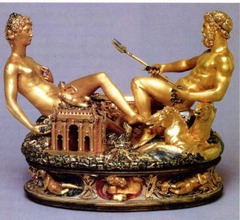

Hercules and Antaeus

c.1475

* the three-dimentianal form brings great and strong sense of motion

*: the use of pagan figures shows a new trend in Renaissance art that was not totally against the classical subject matter—- shifted and more relaxed attitude

*: Hercules was one of the patrons of Firenze

*: limbs seem to move outward in every direction, so the viewer must examine it from all the aspects

*:

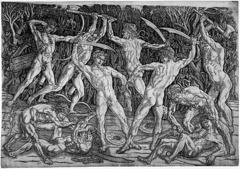

Battle of the Ten Nude Men

c. 1465-1470

*: vibrant motion dynamics

* the use of sculptural depiction on the flat surface, ep, two sides of one man’s body was shown

Doubting of Thomas

Or San Michele, Florence

1467-1483

* a symbol for justice: the gild

*: this sculpture shares with contemporary paintings an interest in textures, the play of light and dark in massive drapery folds, and illusionism

* the eloquent poses and bold exchange of gestures between Christ and Thomas convey the drama of the scene;

* the active drapery, with its deep folds, suggest the calm of Christ and the disturbance in Thomas’s mind

David

c.1475

*: less femininity

*: dressed

Equestrian Moment of Colleoni

Venice

c. 1483-1488

*: horse with forwarding position shows great movement and dynamic

*: graceful and spirited horse

*: thin hide reveals veins, muscles, and sinews, in contrast to the rigid surfaces of the armored figure bestriding it

*: forceful dominance

*:

Marriage of the Virgin

1499-1504

Adoration of the Magi

1423

*Gothic: use of flat gold foils as halo

architectural frames

crowded composition

barely visible gold sky

continuous narrative

narrative stripes down the frame called Predella

stacked perspective

* Renaissance: the attempt of deploying perspectives: the groom boy and the horse

the subject matter comes from Florentine bankers’ seeking for salvation

* lavish triple-arched gilt frame of the altarpiece

* gable figures

* the combination of unified landscape and several episodes of the same story

* elegant figures, garbled in brocades, surrounded by colorful retainers

* gold leaf and tooled surface

* the pseudo-kufic inscriptions on the virgin and child’s halo attest to Gentile’s contact with Islamic works

* the three kings also represent the three ages of men

* A golden light unites the whole image, illuminating the bodies of the animals, the faces of the humans, and parts of the landscape

* the forms are softly modeled to suggest volume for the figures and to concentrate the strong flattening effect of the gold

* the predella shows gentile’s use of light to over the line and eliminate forms

* the mythical light carries symbolic meanings

* refined style

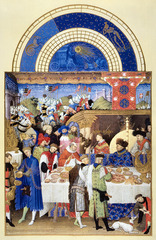

Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry

January&July pages

1413-1416

already showing space on a flat surface

The Expulsion from Paradise

Brancacci Chapel, Florence

1424-1427

* the nudity in a chapel brings a new momentum to biblical representation

*: fresco

* shows the human body in motion

* narrow format of this fresco leaves little room for a spatial setting

* the soft, atmospheric modeling, and especially the boldly foreshortened angel, convey a sense of unlimited space.

* the grieve-striken Adam and Eve are striking representations of the beauty and power of the nude human form

* in contrast to the fluid grace of Gentile’s painting, Masaccio;s paintings represent a less beautiful reality

The Tribute Money

Brancacci Chapel, Florence

1424-1427

* fresco

* yellow&blue combo: symbol for St. Peter

* break-through: halos drawn in perspectives: instead of being represented as flat gold disks, they are visualized as actual objects

* the vanishing point being on Jesus’s face makes all the octagonal lines subliminal arrows that direct our attention to the central figure: symbolic resonance

* isocephalic arrangement: all the figures’ heads basically on the same level, and in here specially circularly arranged

* Masaccio uses perspective to create a deep space for the narrative and to link the painting’s space to the space of the viewers

* Masaccio models the forms in the picture with light that seems to have its source in the real window of the chapel

* He also uses atmospherical perspective in the subtle tones of the landscape to make the forms somewhat hazy

* shows his ability to merge the weight and volume of Giotto’s figures with the new functional view of body and drapery

* Fine vertical lines scratched in the plaster establish the axis of each figure from the head to the heel of the engaged leg. In accord with this dignified approach, the figures seem rather static.

* Instead of employing violent physical movement, Masaccio’s figures here convey the narrative by their intense glances and a few strong gestures.

*: relies on architectural elements to make up the pictorial space

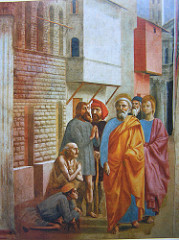

St. Peter healing with his Shadow

Brancacci Chapel, Florence

1424-1427

* vanishing point arranged outside the picture as an adjustment to its position in the chapel

*: relies on architectural elements to make up the pictorial space

*: subtly and immediacy

The Trinity

S, Maria Novella, Florence

1425

*: perfect one-point perspective

*: vanishing point arranged at the eye level to create both looking up and down: subject matter

* donors positioned in the painting both outside and lower

* the use of momentum memoir: sarcophagus

* the large scale, balanced composition, and sculptural volume of the figures have origins in the work of Giotto, but differently, Masaccio’s drapery falls in response to the body underneath

* The setting reveals the artist’s awareness of Brunelleschi’s new architecture and his system of perspectives

* the picture space is independent of the figures

* the figures inhabit the space but they do not create it

* the space seems measurable, palpable

* Masaccio further expresses the theme of the trinity by the triangular composition that begins with the donors and rises to the halo of God

* color balances the composition too, as opposing reds and blues unite in the garment worn by God

* The whole scene has a tragic air, made more solemn by the calm gesture of the Virgin, as she points to the Crucifixion, and by the understated grief of St. John the Evangelist

* The reality of death but promise of resurrection is an appropriate theme for a funerary commemoration

*: the first expression of the full potential of perspective

*: Masaccio uses the perspective construction to reinforce the conventions of the religious life

*: Instead of a hierarchy of scale, Masaccio introduces a hierarchy of hierarchy of levels. Echoed by how the architecture gets more and more richly ornamented when ascending

*: While all of the figures are modeled in space-the viewers look up at the figures so that the underside of Mary’s hand is more visible, we look up at John’s chin and up at he face of Christ-God evades the pictorial space and is presented fully frontal and parallel with the picture plane. This is no earthly being, unlike the other figures in the fresco, so he cannot inhabit the same space;

*: Only by having such a controlled space can God be depicted as transcending that space

Annunciation

c. 1440-1445

partly due to the artist’s own religion

* gentle lines and colors

* old-fashioned: flat gold halos, grass spangled with flowers, mild emotions, distorted proportions

* new element: the use of perspectives in architectural depiction

*: Angelico sets the angel and Mary into a vaulted space very similar to the real architecture of the convent, itself inspired by Brunelleschi

*: A perspective scheme defines the space, although the figures are too large and stand comfortably in it

*: The Virgin and the angel Gabriel glance at each other across the space; they humbly fold their hands, expressing their submission to divine will;

* the forms are graceful, and the overall scene is spare, rather than extravagant

*: the colors are pale, the composition has been pared to the minimum, and the light baths all the forms in a soft glow

* Angelico’ composition has the simplicity and spatial sophistication of Masaccio, with figures that are as graceful as Gentile da Fabriano’s.

* The fresco enhanced their life of prayer and contemplation, as was the goal of such imagery in religious communities

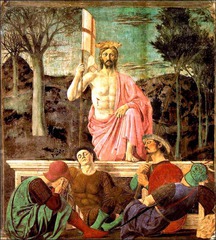

Resurrection

Borgo S. Sepolcro

c. 1463

* dramatical quality

* large forms

* high plasticity in color, texture and shape

* trees serving as symbols: passage from death to life: speaking for the subject matter

* The unconscious soldiers are depicted with their heads foreshortened in “real” space, the resurrected Christ is represented without any foreshortening, and like the sarcropagus from which he rises, fully frontal

* By using single-point prospective, the painters of Trinity and Resurrection can communicate with us with a directness unimaginable before Brunelleschi’s experiments because they are constructed by taking into consideration the relationship of the viewers with them.

*: Jesus’s frontality and the triangular composition may derive from works like Trinity

*: Piero pays special attention to the arrangement of the Roman soldiers, they are variations on a theme of bodies in space

*: Jesus: so perfect his anatomy and so serene his aspect as he triumphs over death;

Portraits of Battista Sforza and Federico da Montefeltro

c. 1472

* continuous landscape

* full profile widely used in the 15th century probably due to the heritage of ancient coins

*: this painting shows Pietro’s mastery of spatial representation and clarity of forms by using the rich hues and varied textures made possible by oil painting.

*: A shadow falls over the landscape behind her, while the landscape behind her and her husband is lighter and busier. The rigid profile placed against the low horizon and deep landscape give the figures an unapproachable and monumental appearance

*: balanced and spacious composition results in an image of calm authority and triumph

Merode Altarpiece

1425-1430

*: Orthogonal lines adjusted to meet at the roughly the same place

*: the main goal is visibility: objects and furniture manipulated within the space to make them more obvious

*: the far end of the bench on which the Virgin is perched is deliberately raised so that it can be seen, while the table top is tipped forward so that all of the objects-symbols of virgin’s purity-are more easily read

*: the knee under the dress shows the study of anatomy

*: the extent of details is not italian

*: symbolism: lily/towel: pureness and virginity —–iconography

*: the study and appliance of shadows

*: lit from windows of two walls: subtlety of light and multiple shadows

*: where there are orthogonal lines, they meet in general vanishing points rather than precise points, combined they draw our attention to the hands of the figures

*: no single element is subordinated to any other: incidental details such as the mirror on the wall or the window are works of art themselves

*: not perfect notion of perspective

*: subtle gradation of texture

*: the mirror brings a playful 3-dimentionality

*:

Descent from the Cross

1435-1438

oil on panel

*: all the figures are arranged parallel to the picture plane in a box-like space, like a painted version of a carved altarpiece,

*: the shallow space serves to emphasize the intense emotions of the scene, while Rogier’s graceful linear abstractions produce a painting which does not purport to depict reality

*: it is a sophisticated two-dimensional painting pretending to be a three-dimentional carved altarpiece

*: the tension between the picture surface and the illusionistic space so evident in Rogier’s painting was something that used to be characterized as the evolution of painting in the Netherlands in the first half of the fifteenth century. suggesting that the artists were thinking alongside the same lines as the Italians about the limitations of the picture plane

*: painting/sculpture ambiguity

*: the parallel between Jesus and the Virgin

*: set in a niche–fashion at that time

*: Gothic tracery elements

*: combination of profoundness and playfulness

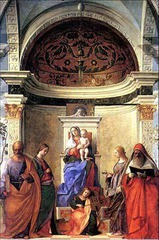

St. Lucy Altarpiece, 1450

*: the architectural space is constructed so that the orthogonal lines converge on a point between the Virgin’s knees.

*: altho the space appears convincing, the perspective construction is hidden, perhaps deliberately , by the use of curves and avoidance of obvious orthogonal lines

*: reconstructed in plan, the space seems unlikely because on a plan the gap between the Virgin and the architecture would have to be very wide for the niches to frame the different figures as they do.

*: Domenico’s intention seems to have been to create an image reminiscent of a more conventional polyptych in which all of the saints would have had their own separate panel

*: the tops of the front arches touch the edge of the picture as though they are meant to be read as part of the frame, although the bases of the columns occupy the pictorial space behind the saints

*: the central shell niche is positioned not so much to form a convincing interior but to frame the Virgin and Child

*: as a result Domenico has created an altarpiece that extends the conventional sacra conversazione with figures depicted in clear spatial relationship with one another and lit by a consistent light source

Madonna and Child with saints

1472-1474

*: pointing the child’s body to a certain direction to show his destiny

*: vanishing pointing on the Virgin’s neck

*: The background consists of the apse of a church in Renaissance classical style.

*: The Child wears a necklace of deep red coral beads, a color which alludes to blood, a symbol of life and death, but also to the redemption brought by Christ. Coral was also used for teething, and often worn by babies

*: The characters’ clothes, the angels’ jewells, Federico’s armor and the oriental carpet beneath the feet of the Virgin are depicted in great detail, reflecting the influence of Early Netherlandish painting.

*: The apse ends with a shell semi-dome from which an ostrich egg is hanging. The shell was a symbol of the new Venus, Mary (in fact it is perpendicular to her head) and of eternal beauty; in fact, differently from the Greek goddess, Mary’s beauty will remain eternal in the Kingdom of God.

*: The egg is generally considered a symbol of the Creation and, in particular, to Guidobaldo’s birth; the ostrich was also one of the heraldic symbols of the Montefeltro family.

*: Such an egg often hangs over alters dedicated to the Virgin.

*: It was believed that the ostrich let her egg hatch in the sunlight without intervention, and thus became a symbol of virgin birth. Also, the ostrich is here an absent mother, a symbol of the deceased Battista.

*: the artist’s mastery of proportions is remarkable; it is almost symbolized by the large ostrich egg hanging from the shell in the apse. The shape of this symbolic element is echoed by the near perfect oval of the Madonna’s head, placed in the absolute centre of the composition

*: In this painting Piero places his vanishing point at an unusually high level, more or less at the same height as the figures’ hands, with the result that his sacred characters, placed in a semicircle, appear less monumental.

*: Piero’s extraordinary invention of an architectural apse echoed below by another apse, consisting in the figures of the saints gathered around the Madonna, was taken up time and again by artists working at the end of the 15th century and at the beginning of the 16th, particularly in Venice, starting with the almost contemporary paintings of Antonello da Messina and Giovanni Bellini. This organized composition, typical of Piero’s work, contained within a unity of space and lighting, seems however to have a new feel about it, as though the artist were taking part in the new currents being developed in Italian art after 1470.

*: The new trends are dictated primarily by the great popularity that Netherlandish painting was enjoying, particularly in Urbino. The most descriptive and ‘miniaturistic’ aspects of Netherlandish painting are echoed in the Brera altarpiece in the Duke’s shining armour, for example, and in the stylized decoration of the carpet.

*: Netherlandish art was popular among the patrons of the period as well, as we can see by the rings on Federico’s hands, which Piero had painted by Pedro Berruguete, a Spaniard with a Northern training.

*: The angels’ garments are decorated with jewels and with huge precious brooches, their hair is held back by elegant diadems: these elements, and even their melancholy expression, are certainly influenced by the recent developments in Florentine art

Last Supper

S. Apollonia, Florence

c. 1445-50

*: The arrangement of balanced figures in an architectural setting is particularly noted

*: Saint John’s posture of innocent slumber neatly contrasts Jude the Betrayer’s tense, upright pose, and the hand positions of the final pair of apostles on either end of the fresco mirror each other with accomplished realism.

*: The colors of the apostles’ robes and their postures contribute to the balance of the piece.

*: Andrea del Castagno (1423-1457) was well known for the emotional expressionism and naturalism of his figure style

*: balance between human figure and architecture

*: He portrayed movement of body and facial expression, creating dramatic tension.

*: Castagno brought to painting what Banco and Donatello brought to sculpture for Florentine artists. This influence carried great weight through the Renaissance, finding a masterful pinnacle in the work of Michelangelo.

*: the sobre architectural structure of the room where the scene of the Last Supper is taking place: a room in the austere style of Alberti, with the lavish coloured marble panels functioning as a backdrop to the heavy and solemn scene of the banquet

*: Notice also the beauty of some of the minor details, such as the gold highlights in some of the characters’ hair or the haloes depicted in perfect perspective.

*: The detail and naturalism of this fresco portray the ways in which del Castagno departed from earlier artistic styles. The highly detailed marble walls hearken back to Roman “First Style” wall paintings, and that the pillars and statues recall Classical sculpture and preface trompe l’oeil painting. Furthermore, the color highlights in the hair of the figures, flowing robes, and a credible perspective in the halos foreshadow advancements to come.

*: The treatment of the Last Supper was a serious challenge for Renaissance painters, who had to depict thirteen figures while retaining diversity and interest.

*: Castagno created an engaging space with imitation marble wall plaques and the sharply foreshortened floor and ceiling.

*: An extraordinary element of this fresco is the remarkable balance of gestures and expressions, particularly in the group of figures in the centre of the composition, where the innocent sleep of St John to the left of Jesus is contrasted to the tense, rigid figure of Judas sitting opposite.

*: Andrea del Castagno’s Last Supper (1447) is typical of the Early Renaissance. The use of linear perspective in combination with ornate forms such as the sphinxes on the ends of the bench and the marble paneling tend to detract from the spirituality of the event.

David

c.1450-1457

*: in the middle of motion

*: draped

*: Images of young David, who overcame seemingly insurmountable odds to kill the giant, were popular in fifteenth-century Florence, the smallest major power in Italy.

*: like many early Renaissance artists, Castagno has presented the action and its outcome simultaneously: David holds the loaded sling, but already the head of the slain Goliath lies at his feet. David’s energetic pose, based perhaps on an ancient statue, creates a strong contour that would have been clear and “legible” as the shield was carried. Nevertheless, the youth’s body is well modeled, rounded with light and shadow to give a convincing likeness of a body in action.

Battle of San Romano

c.1438

*: fallen weapons passing for perspective

*: set in a landscape

*: orthogonal grid

*: the central panel of a large triptych painted by Paolo Uccello

*: What makes this cycle a masterpiece is the bold and experimental use of the perspective who made Uccello famous.

*: The composition is very crowded, but despite that the atmosphere is somewhat unreal and the knights look like fake dummies of a medieval tournament. Paolo Uccello is more interested in the perspective and its application than in the human feelings.

*: The naturalistic details, the hunting scenes in the background, the finicky description of the armors and the horses remind us of the fairy-tale gothic aestethics.

*: Paolo Uccello is indeed an important transition artist, fully in love with the Renaissance revolution of Renaissance but winking at the gothic tradition.

*: Plastic shapes of the figures and horses march across a grid consisting of discarded weapons and pieces of armor; these objects form the orthogonals of a perspective scheme that is neatly arranged to include a fallen soldier;

*: a thick hedge of bushes defines this foreground plane, beyond which appears a landscape that rises up the picture plane, beyond which appears a landscape that rises up the picture plane rather than receding deeply into space;

*: spots of brilliant color and a lavish use of gold reinforce the surface pattern, which would have been more brilliant originally, as some of the armor is covered in silver foil that has now tarnished

*: Such splendid surface reminds us of the paintings of Gentile da Fabriano

*: Uccello’s work owes much to International Gothic displays of lavish material and flashes of natural observation, with the added element of perspective renderings of forms and space;

Primavera

c.1482

*: Among the many theories proposed over the last decades, the one that seems to be the most corroborated is the interpretation of the painting as the realm of Venus, sung by the ancient poets and by Poliziano (famous scholar at the court of the Medici). On the right Zephyrus (the blue faced young man) chases Flora and fecundates her with a breath. Flora turns into Spring, the elegant woman scattering her flowers over the world. Venus, in the middle, represents the “Humanitas” (the benevolence), which protects men. On the left the three Graces dance and Mercury dissipates the clouds.

*: The Allegory of Spring is a very refined work of art. The naturalistic details of the meadow (there are hundreds of types of flowers), the skillful use of the color, the elegance of the figures and the poetry of the whole, have made this important and fascinating work celebrated all over the world.

*: what is certain is the humanistic meaning of the work: Venus is the goodwill (the Humanitas), as she distinguishes the material (right) from the spiritual values (left). The Humanitas promotes the ideal of a positive man, confident in his abilities, and sensitive to the needs of others.

*: This ancient conception was on the way to Renaissance Humanism and Neoplatonic ideals moving around the Medici court. Neoplatonism was a philosophical and aesthetic movement trying to blend the thought of Greek philosopher Plato with the noblest concepts of Christianity. The Neoplatonic conception of the ideal beauty and the absolute love influenced the Renaissance culture and Botticelli.

*: Religion no longer needed to be the main subject of artist work.

*: This story alone shows that this painting was meant to celebrate a marriage

*: Also symbolic of love and fertility are the oranges growing in the grove. The Medici family had an orange grove on the family estate. The number of oranges Botticelli drew clearly represented the hope that this marriage would result in many offspring.

Birth of Venus

c.1485

*: Many aspects of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus are in motion. For example, the leaves of the orange trees in the background, ringlets of hair being blown by the Zephyrs, the roses floating behind her, the waves gently breaking, and the cloaks and drapery of the figures blown and lifted by the breeze.

*: Botticelli’s Venus was the first large-scale canvas created in Renaissance Florence.

*: He prepared his own tempera pigments with very little fat and covered them with a layer of pure egg white in a process unusual for his time. His painting resembles a fresco in its freshness and brightness. It is preserved exceptionally well and the painting today remains firm and elastic with very little cracks.

*: Birth of Venus is dependent on the delicacy of Botticelli’s line. The proportions show their greatest exaggeration, yet the long neck and torrent of hair help to create the mystifying figure.

*: open and deep tonality

*: the shallow modeling and emphasis on outline produce an effect of low relief rather than of solid, three-dimensional shapes. The bodies seem to be drained of all weight, so that they float even when they touch the ground

*: the ethereal figures re-create ancient forms

Delivery of the Keys

1482

*: As far as the composition is concerned, the most striking element is line, through which Perugino almost left us with a textbook case study of one-point linear perspective.

*: While the series of horizontal lines divide foreground from background, the diagonal orthogonal lines create the appearance of depth as they converge at the vanishing point near the doorway of the building in the background.

*: The result is that the scene takes place on what appears to be a large grid which allows viewers to quite clearly ascertain the distance between figures in the foreground, middle ground, and background.

*: In addition, Perugino used aerial perspective to make the hills on either side of the temple appear to fade into the background.

*: Both types of perspective help the viewer understand visually that the scene is anchored realistically in three dimensions, even though it was obviously painted on a two-dimensional picture plane.

*: In the fresco, Christ is shown in the middle, literally giving St. Peter keys (alluding to the “keys to the kingdom of heaven”), while the apostles stand in groups behind them.

*: Quite clearly, the handing of the keys to Peter is meant to frame the Catholic doctrine of apostolic succession by which Christ handed power to Peter, and hence onto the popes.

*: Christ and Peter are the figures of prime importance in this scene, and the importance of spiritual authority (embodied in the keys) is particularly emphasized by the key which hangs down vertically along the axis where the vanishing point is located.

*: The setting is a piazza, which is very spacious and airy. It is not a piazza from real life, but instead an idealized one with a temple in the middle of it. Aided by the grid-like ground pattern, we see separate groups of figures in the middle ground on both left and right sides of the piazza. These are scenes from episodes of the Gospels – one in which Christ says “render unto Caesar”, and the other in which the crowd is getting ready to stone Christ before he escapes.

*: The looming structures in the background are particularly notable. The temple is centrally-planned and domed, presumably with eight sides. For pilgrims visiting the Holy Land, the Temple of Solomon was thought to be associated with the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, and so what we are seeing here is based on a similarly octagonal and domed form.

*: On either side of the temple, monumental arches stand decorated with reliefs and gilded surfaces. These are triumphal arches of the kind built by the ancient Romans. These particular arches, however, resemble one very specific arch built in Rome around 312 A.D. – the Arch of Constantine, who reigned as emperor from 306-337 A.D. Constantine was the first emperor to legalize the profession of the Christian faith in the empire after centuries of Christian persecution by pagan emperors, and he was also the patron of the greatest churches of the late antique period. One of these churches was the (Old) Basilica of St. Peter, which became the seat of the pope in Rome. It was also thought that Constantine was the first to officially recognize papal authority. Again, this underscores the idea of papal authority.

*: Overall, the scene is one showing a critical Biblical episode for the popes, and one which makes excellent use of Renaissance perspectival devices to create the illusion of depth on a two-dimensional surface.

*: The style of the figures is dependent upon Verrocchio. The active drapery, with its massive complexity, and the figures, particularly several apostles, including St John the Evangelist, with beautiful features, long flowing hair, elegant demeanour, and refinement recall St Thomas from Verrocchio’s bronze group on Orsanmichele. The poses of the actors fall into a small number of basic attitudes that are consistently repeated, usually in reverse from one side to the other, signifying the use of the same cartoon. They are graceful and elegant figures who tend to stand firmly on the earth. Their heads are smallish in proportion to the rest of their bodies, and their features are delicately distilled with considerable attention to minor detail.

*: The gravely symmetrical design coveys the spatial importance of the subject in this particular setting: the authority of St. Peter as the first pope, as well as of all those who followed him, rests on his having received the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven from Christ himself

*: The figures have the crackling drapery and idealized figures of Verrocchio

*: HIghly individualized features

*: the gravely symmetrical design conveys the special importance of the subject in this particular setting: the authority of St. Peter as the first pope, as well as of all those who followed him, rests on his having received the keys to the kingdom of heaven from Christ himself. The figures have the crackling drapery and idealized figures of Verrocchio. A number of bystanders with highly individualized features witnessing the solemn event

*: in the vast background, two further narratives appear: to the left, in the middle distance, is the story of the tribute money; to the right, the attempted stoning of Christ; the inscriptions on the two Roman triumphal arches favorably compare Sixtus IV to Solomon, who built the Temple of Jerusalem. These arches flank a domed structure seemingly inspired by the ideal church of Alberti’s Treatise on Architecture,

Martyrdom of St. Sebastian

c.1450s

*: The idealized figure of the saint is set against a temple fragment painted with a masterly sense of the texture of both carved and broken rock. Mantegna juxtaposed the saint’s real foot with a foot fragment of a statue, playing on the paragone theme in a demonstration of the versatility of painting

*: The landscape background is close to that in the Meeting Scene in the Camera Picta, confirming the works’ chronological proximity.

*: The Roman martyr St. Sebastian almost resembles a stone sculpture here, and we experience first hand the rounded body contours achieved in the distinct moulding of the figure.

*: The background stretches forever behind the figure and is enriched with fragments of ancient architecture. Mantegnas signature on the column of the Triumphal Arch is written in Greek, more evidence of his extensive knowledge of the ancient world.

*: Firstly, Sebastian was given the designation as the patron saint of athletes because of his physical endurance and way of spreading the Faith. … In addition to the title of patron saint of athletes, Sebastian was named the patron saint of those afflicted with plague.

*: It is placed against a Corinthian column (with a glancing illusion to Vitruvius’s equation between architectural and bodily proportions). Yet in this, as in many other fifteenth-century religious pictures, the pagan world is shown symbolically in ruins.

*: Fragments of statues and reliefs lie on the ground, the building (based on the arch of Septimius Severus in Rome) is fissured and broken. The apparent contradiction is, however, essential to the meaning of the painting – Christianity, personified by the saint, prevails over all human ills and disasters.

*: St Sebastian was a patron of the sick and his intercession was evoked especially in times of plague, of which there were outbreaks (probably bubonic) every 15 years or so in Venice throughout the century.

*: anatomically precise and carefully proportioned – classical resonance

*: these forms are crisply drawn and modeled to resemble sculpture

*: signature in greek

*: a road leads into the distance, transversed by the archers who have just shot the saint; through this device, Mantegna lets the perspectively constructed space denote the passage of time

*: atmospherical landscape

*: later-afternoon sunlight: melancholy mood

*: the light-filled landscape in the background indicates Mantegna’s awareness of Flemish paintings, which had reached Florence as well as Venice around 1450

*:

Duke Gonzaga of Mantua and his Court

Frescoes in the Ducal Palace, Mantua

1465-74

Oculus

Frescoes in the Ducal Palace, Mantua

1465-74

Lamentation over the body of Christ

c. 1480

*: Unlike most religious art of the Early Renaissance, this is not an idealized portrait of Jesus: the nail holes in the hands and feet, the discolouration of the skin, and the dramatic perspective of the foreshortened body lend it a coldness and a realism belonging to the mortuary slab.

*: A common theme in many religious paintings, the ‘Lamentation Over the Dead Christ’ is not a Biblical theme at all. It does not appear in any of the New Testament gospels, and only emerged as a devotional image during the 11th century.

*: His picture is defined from the outset by its window-like frame. This emphasizes the confined space of the scene and makes it appear even more like the cold slab of a morgue. It also gives the viewer, positioned at Christ’s feet, a dramatic close-up of Christ’s dead body: the physicality and naturalism are extraordinary – it looks completely lifeless.

*: The static nature of the body is further enhanced by a series of vertical and horizontal lines in the painting. The vertical ones comprise the position of the corpse, notably its arms and legs; and the right edge of the table. The horizontal ones are seen in the left/right axis of the pillow, the left/right flow of the shroud, and the bottom edge of the painting. These lines reinforce the stillness and immobility of Christ.

*: Within this grid however, Mantegna creates an illusion of movement, of life. The weeping Mary is dabbing her eye with a handkerchief; the damp, bloody shroud swirls across the lower half of the picture. Even Christ’s hair has a wild look. This contrasting appearance of motion helps to create a tension which attracts our attention, as do the elements which are visible only at second glance, like the face of Saint John (left edge), or the ointment container (top right).

*: This uncomfortably realistic representation of death, further enhanced by the picture’s muted colour scheme, and wax-like flesh tones, leaves no room for idealized musings or religious rhetoric. This picture is about the banal physicality of death – the end of earthly life. A fact and a prospect which is only relieved by our faith in God and a life after death. This may be the key message of the work.

*: Mantegna’s principal contribution to Early Renaissance painting was his mastery of trompe l’oeil spatial illusionism, exemplified by his foreshortening technique both in this painting and in his fresco painting on the ceiling of the Camera degli Sposi (room of the bride and groom) in the Ducal Palace, Mantua (1471-74). Foreshortening, namely the application of linear perspective to a single object or figure in order to simulate projection or depth (thus creating the illusion of three-dimensionality), helps to render the appearance of objects as we perceive them. Thus Mantegna’s Christ is shown greatly truncated, even though the artist had to deliberately reduce the size of the feet so as not to obscure our view of the body. If a photograph had been taken from the same viewpoint, the feet would have blocked our view of the torso.

*: The theme of the Lamentation is common in medieval and Renaissance art, although this treatment, dating back to a subject known as the Anointing of Christ is unusual for the period

*: Most Lamentations show much more contact between the mourners and the body. Rich contrasts of light and shadow abound, infused by a profound sense of pathos

*: The realism and tragedy of the scene are enhanced by the violent perspective, which foreshortens and dramatizes the recumbent figure, stressing the anatomical details: in particular, Christ’s thorax.

*: The holes in Christ’s hands and feet, as well as the faces of the two mourners, are portrayed without any concession to idealism or rhetoric. The sharply drawn drapery which covers the corpse contributes to the dramatic effect. Unique to this painting is a design that places the central focus of the image on Christ’s genitals – an artistic choice that is open to a multitude of interpretations. Mantegna managed instead to paint a very specific representation of physical and emotional trauma.

*: Mantegna presented both a harrowing study of a strongly foreshortened cadaver and an intensely poignant depiction of a biblical tragedy. This painting is one of many examples of the artist’s mastery of perspective. At first glance, the painting seems to be a strikingly realistic study in foreshortening .

*: Looking in we see an almost monstrous spectacle: a heavy corpse, seemingly swollen by the exaggerated foreshortening. At the front are two enormous feet with holes in them; on the left, some tear-stained, staring masks. But another look dissipates the initial shock, and a rational system can be discerned under the subdued light.

*: The face of Christ, like the other faces, is seamed by wrinkles, which harmonize with the watery satin of the pinkish pillow, the pale granulations of the marble slab and the veined onyx of the ointment jar. The damp folds of the shroud emphasize the folds in the tight skin, which is like torn parchment around the dry wounds. All these lines are echoed in the wild waves of the hair.

*: Mantegna’s realism prevails over any esthetic indulgence that might result from an over-refined lingering over the material aspects of his subject

*: His realism is in turn dominated by an exalted poetic feeling for suffering and Christian resignation

*: Mantegna’s creative power lies in his own interpretation of the “historic,” his feeling for spectacle on a small as well as a large scale. Beyond his apparent coldness and studied detachment, Mantegna’s feelings are those of a historian, and like all great historians he is full of humanity. He has a tragic sense of the history and destiny of man, and of the problems of good and evil, life and death.

*:

Ghent Altarpiece (closed)

1432

polyptych

*: subtle touches of color

*: marble statue kind of quality

*: four identical niches to indicate the architectural space

*: mortal patrons are signified as human forms instead of marble

*: but in here the patrons aren’t shown in perfect profile

*: infinite patience and attention to detail, gives the work its breathtaking technical virtuosity.

*: One of the greatest examples of early Flemish painting, the Ghent Altarpiece is acclaimed for its brilliance of colour and wide-ranging subject matter, which includes full-length nudes, vivid portrait art, landscapes, sumptuous robes and numerous examples of still life. Not for nothing did the great German master Albrecht Durer describe it as a stupendous piece of religious art.

*: Annunciation, underneath which are two remarkable grisaille panels containing illusionistic statues

*: These faux sculptures represent John the Baptist, holding the traditional symbol of the lamb, and John the Evangelist, author of the Apocalypse. Flanking the saints at each end, are separate paintings of the donor and his wife, Lysbette Borluut, kneeling in prayer. The whole visual effect is deliberately muted – only the portraits of the donors contain any real colour – probably in order to heighten the effect of opening the altarpiece to reveal the paintings inside

*:

Ghent Altarpiece (open)

1432

polyptych

*: iconography: the lamb

*: very subtle light reflection and refraction on the crown

*: high naturalism seen in Adam and Eva

*: As soon as the polyptych is opened, the viewer is dazzled by an explosion of red and green colour pigments.

*: The pictures themselves are laid out in two registers or tiers. In the top tier, comprising three central panels and two wing panels at each end, we see an enthroned Christ the King, flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist. To offset the austere gravity of this central trio, they are flanked by paintings of angels singing and playing the organ

*: The angel’s clothes, instruments and surroundings are depicted in meticulous detail. Jan van Eyck’s masterly use of oil paint creates tiny vibrations of light within the dense, saturated colours, most of which are full of symbolic significance.

*: The beauty of the fabrics and the musical instruments demonstrate the creative capacity of man, which in turn alludes to the overarching role of the Creator himself. At either end of the upper tier, Van Eyck painted two stunning life-size portraits of Adam and Eve, depicted with extraordinary naturalism. These figures are among the most naturalistic of all male nudes and female nudes of the European Renaissance. They are surmounted by illusionist bas-reliefs featuring the sacrifice of Cain and Abel and the killing of Abel.

*: The centre of the lower tier, underneath the upper trio of Jesus, Mary and John, features a single large painting, from which the altarpiece takes its name. It shows the Eucharistic sacrifice of the Mystic Lamb (the symbol of Christ), placed on an altar surrounded by fourteen angels and set in a fertile meadow hedged with bushes, on the outskirts of a city. Four groups approach or occupy the meadow. Top left, we see a procession of bishops and cardinals. Top right, there approaches a group of female martyrs bearing palm leaves, symbols of their martydom. Bottom left, we see a group of kneeling Jewish prophets behind whom are a collection of pagan philosophers and scholars drawn from all over the world, as evidenced by their different styles of headgear. Bottom right, we see the twelve Apostles, followed by Popes and other clergy. Saint Stephen is shown carrying the rocks of his martyrdom.

*: All these groups look towards the altar in the centre of the meadow. The angels surrounding the altar hold the instruments of the Passion – the pillar against which Christ was lashed, the nails used to pin him to the cross, and the sponge dipped in vinegar. Blood is pouring from the lamb’s body into a chalice. And here we see the real meaning of the Ghent Altarpiece – sacrifice, blood, and the role of the clergy in administering the holy sacraments.

*: Situated in front of the altar is the ‘Fountain of Life’. Thin trickles of water fall into a channel which flows out of camera towards the viewer. The message is: the blood of Christ gives us life. Indeed a Latin inscription on the altar states: “Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world.”

Man with a red Turban

1433

*: panel paintings

*: Van Eyck’s technical contribution to the art of oil painting – notably his meticulous use of thin layers of transparent colour pigments for maximum luminosity – made possible the precise optical effects and mirror-like polish that make this portrait so lifelike.

*: Note, for example, the effects of the two-toned stubble or the capillaries on the white surface of the left eye.

*: His use and application of colour has been commented on by numerous artists and critics: here, for instance, the white colour of the eye is mixed with tiny amounts of red and blue. A very thin layer of red is dragged over this underlayer, but in such a way as to leave the underlayer exposed in several places.

*: The iris of the eye is painted ultramarine – with additions of white and black towards the pupil, which is painted in black over the blue of the iris. The main highlights are four touches of lead white – one on the iris and three on the white.

*: The variation of focus between the two eyes suggests that Van Eyck, may have used a mirror to create this image: his right eye is slightly blurred around the edges, appearing to be only passivly engaged in sight, while the outline of the left eye is clearly delineated and focused on a specific object

*: This effect probably resulted from the artist observing himself in the mirror; when viewing oneself from an angle both eyes cannot be seen simultaneously.

*: Through his control of the medium, Van Eyck becomes ineffably present in the image, if not through his physical likeness, then through the way in which he alone has the skill to render invisible the mark of each brushstroke.

*: As in all his paintings, Van Eyck designs his composition with great care. Here, for instance, he relies heavily on colour and shade for effect. The rich red folds of the turban or chaperon frame and contrast with the lighted face which emerges from the darkness.

*: And the viewer is irresistibly drawn into the image by the firm gaze of the sitter, from which nothing else is allowed to detract. His use of chiaroscuro is masterly, as is his dramatic tenebrism. Van Eyck’s combination of tonal control and use of shading, anticipates the High Renaissance technique of sfumato, exemplified in the portraiture of Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519).

*: Van Eyck uses light and shade in a subtle and dramatic way: the sitter seems to emerge from darkness, his face and headdress modelled by the light that falls from the left. The viewer is drawn towards the image by the penetrating gaze of the sitter.

St. Luke drawing the Virgin (1435-1440)

*: In it Rogier exquisitely combined the Gothic legacy of stylized patterning with a new sense of naturalism

*: He did not, however, merely replicate the world around him, but manipulated details to create an intricate program of symbols.

*; For example, the enclosed garden in this painting refers to the Virgin’s purity while the carved figures of Adam and Eve on the arms of the throne symbolize Christ’s and Mary’s roles in redeeming humankind from original sin. Rogier may have modeled Saint Luke’s features on his own.

*: This work shares the solidity and monumentality of its figures with the Deposition (Prado, Madrid), but differs from it in a striking atmospheric effect of chiaroscuro, a quality typical of the art of Jan van Eyck.

*: As well as the ideas about the atmospheric use of light and shade that Rogier derived from this picture, he also adopted its overall construction and many motifs from Jan van Eyck’s painting, including the colours of the garments worn by the main figures. They are arranged in the picture as in the van Eyck model, except that the Virgin and her companion have changed sides.

*: In spite of the inspiration Rogier had gained from Jan van Eyck, his St Luke Madonna is an entirely independent depiction of the subject, and was to establish a new tradition.

*: in a departure from earlier paintings of the subject, Rogier’s saint is not himself painting the Mother of God but recording the silverpoint drawing. This corresponds to the practice of contemporary portraiture, and also emphasizes the spiritual significance of the picture more than the long, craftsmanlike activity involved in painting itself.

*: By comparison with other works by Rogier, the extremely picturesque qualities of the chiaroscuro in the St Luke Madonna are particularly marked. Perhaps the artist, impressed by this effect in the pictures of Jan van Eyck, used it here because the painting not only honoured the saint but also stood for the painter’s craft.

*: Rogier was demonstrating another modern artistic achievement, and thus – whether in homage or in a spirit of rivalry – was referring explicitly to the other famous Flemish painter of his time. On the whole, however, he interpreted his model very much in his own way: where Jan’s figures are embedded in a world of light and shade, Rogier’s figures clearly claim more attention than the rest of the picture. The landscape in the Rolin Madonna seems to stretch backward for ever, suggesting in its countless details the whole teeming fullness of the world. In Rogier’s picture it goes no further than its immediately visible part, and is cut off by architectural features at the sides; similarly the inner room, open to the elements in Jan’s painting, has acquired a ceiling in Rogier’s painting. The small town in the background is animated by little figures (including a man urinating outside the town walls) but it is possible to count them all – what is a whole universe in Jan’s painting here becomes a comparatively flat background for the figures, one that can be completely surveyed.

*: In those figures themselves, however, Rogier shows himself far superior to Jan van Eyck as an innovator. His Virgin is the quintessence of tender maternal love, simultaneously humble and proud; she is presented to the observer in such a way that (unlike Jan’s Madonna) she is effective even without the context of the picture, and may be seen as typical of representations of the Virgin by herself. Instead of the masses of folds in Jan’s painting, her garment in Rogier’s version of the scene forms attractive calligraphic patterns. St Luke is not kneeling motionless before her, absorbed in his work, but is approaching gently like the angel of the Annunciation. Although he is seen in the act of kneeling, it does not jar on the viewer that he could hardly execute a portrait sketch in that attitude, since his activity is not emphasized for its own sake. Instead, his mobile, sensitive hands express both veneration of the Virgin and the intellectual aspect of portraiture. The saint is deliberately captured in a state between movement and repose, which could be the reason why, by comparison with those in the Rolin Madonna, the figures have changed sides: the direction of the saint’s movement runs counter to the usual way of “reading” a picture (from left to right) and is thus inhibited – if St Luke were seen approaching from the left his movement would appear too emphatic.

Portinari Altarpiece

1474-76

*: Painted in Bruges then shipped to Florence, the panel paintings had a significant impact on Renaissance art in the city and beyond, including the Umbrian School of painting, as well as manuscript illustration.

*: The central scene celebrates the joy at the birth of Jesus, but also highlights the humility of the family and the peasants.

*: Three realistic figures of shepherds are kneeling before the Christ child, who – most unusually – is not lying in a crib, but on the ground, surrounded by golden light.

*: For his figures, Van der Goes introduces an old-fashioned hierarchy of scale: the Holy Family are given the largest dimensions, while angels and donors are smaller. The figures are arranged according to diagonal axes around the Virgin Mary, whose hands form the centre of the painting. This unusual arrangement produces a rather unbalanced sense of movement.

*: In the foreground, the exquisite still life – consisting of two vases of flowers and a sheaf of wheat – is a reference to the Eucharist and the Passion.

*: The wheat alludes to the Last Supper, when Jesus broke the bread. The vine leaves and grapes on the vase relate to the wine. The white irises symbolize purity, while the orange lilies refer to the Passion (the red carnations symbolize to the bloodied nails of Christ’s cross); the purple irises and columbine stalks represent the seven sorrows of the Virgin Mary. Thus, taken as a whole, this scene of Christ’s Nativity prefigures the later Salvation which he achieves through his death.

*: On the side panels, kneeling donors are flanked by their patron saints. Portinari, for instance, is shown on the left panel together with his two sons Antonio and Pigello. Opposite, on the right panel, his wife Maria di Francesco Baroncelli is portrayed together with their daughter Margarita. All the donors, with the exception of Pigello, are shown along with their patron saints: Saint Thomas (with spear), Saint Anthony (with bell), Mary Magdalen (with ointment) and Saint Margaret (with book and dragon).

*: The background of the triptych is painted with scenes related to the main theme. Thus on the left, we see Joseph fleeing to Egypt with his pregnant wife; in the central panel, the shepherds are visited by the angel; and on the right, the Three Magi are shown on their way to Bethlehem.

*: When the two side panels are closed, we see a view of The Annunciation, with the two figures – the Virgin of the Annunciation and the Archangel Gabriel – painted entirely in monochrome grisaille technique. The enormous figures, deceivingly rendered to resemble stone sculptures (hence the grisaille), are seemingly inset into their own austere arched recesses, and swathed in thick, flowing robes. The entire trompe l’oeil effect was something quite unknown in Renaissance art in Florence, and many Italian painters sought to imitate its meticulous naturalism. See for example the Adoration of the Shepherds (1485, Sassetti Chapel, Santa Trinita, Florence) by Domenico Ghirlandaio

Virgin and Child with patron portrait

1487

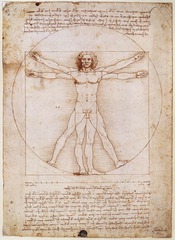

Vitruvian Man

1487

*: magnitude’ and ‘gravity

*: perfect example of Leonardo’s keen interest in proportion.

*: this picture represents a cornerstone of Leonardo’s attempts to relate man to nature

*: through his anatomical drawings and Vitruvian Man as a cosmografia del minor mondo (cosmography of the microcosm). He believed the workings of the human body to be an analogy for the workings of the universe.”

*: study of the male human proportions

*: This iconic image typifies the mix of science and art present in Leonardo’s vision of the world.

Embryo in the womb

1510

*: Leonardo’s philosophy of the human body was often represented by comparisons to architecture. His drawings followed rigorous techniques often employed by architects to depict three-dimensional views of his subjects. He viewed the body as an architectural masterpiece created by nature, in which the skeleton was akin to rocks that laid the foundation for the body.

*: Leonardo’s methods of accurately portraying human anatomy through drawings and diligently mapping out characteristics of the body are considered to have been the foundation of modern anatomical illustration

project for a church

1490

Portrait of Ginevra de’Benci

1474-1478

*: Young women of the time were expected to comport themselves with dignity and modesty

*: An early work, completed when Leonardo was 21, the painting shows an incipient genius and was revolutionary in the history of painting. One of Leonardo’s contemporaries wrote that he “painted Ginevra d’Amerigo Benci with such perfection that it seemed to be not a portrait but Ginevra herself.” Its lifelike and forthright portrayal broke with conventions of earlier Renaissance portraiture of women, including a preference for the more detached profile view. Ginevra de’ Benci is one of the first known three-quarter-view (a representation of a head or figure posed about halfway between front and profile views) portraits in Italian art. She eyes the viewer directly. The planes of her face subtly modeled, she may have “come to life” before viewers in a fashion more vivid than any other painting they had seen before.

*: The marble appearance of her complexion — smoothed with Leonardo’s own hand — is framed by the undulating ringlets of her hair. This then contrasts beautifully with the halo of spikes from the juniper bush. Leonardo veiled the background of this portrait in a thin veil of mist known as sfumato (literal translation: “turned to vapour”); this being created with overlaid oil glazes. Though Leonardo did not create this effect he become well-known for his skillful use of it.

*: Marriage portraits were a common practice at the time and most Florentine portraits of women were painted for just this reason.

*: The juniper plants are a symbol of chastity, highly appropriate for a marriage portrait, as well as being a pun — in Italian — on her name (the Italian name for juniper being ginevra).

*: the young woman stands before a thick hedge of juniper, which is a pun on her name; it is also a symbol of chastity

*: marriage or betrothal occasioned the painting of portraits of women, usually setting them in interiors, wearing expensive jewelry and garments, and often in profile arrangements. Da Vinci broke this mold by setting the young woman out of doors in an atmospheric landscape and in a three-quater view

*: Flemish portraits that had made their way to Florence probably inspired these choices

*: Flemish works definitely informed leonardo’s use of oil as the medium for his paintings

*: Leonardo’s landscape is much more believable and humid-looking.

*: He exploits the oil technique here to blend his brushstrokes very subtly so as to diminish the appearance of contour lines

*: his figures seem to exist only as the result of light falling on three-dimentioal objects

*: starting from a middle tone laid all over the panel, Leonardo renders deep shadows and bright highlights for his forms. In stead of standing side by side in a a vacuum, forms share in a new pictorial unity created by the softening of contours in an envelope of atmosphere.

Madonna of the Rocks

1485

*: The Virgin of the Rocks is the first picture Leonardo is known to have produced in Milan and has stylistic similarities with works painted towards the end of his stay in Florence such as The Adoration of the Magi (Florence) and Saint Jerome (Rome), whose aesthetic concepts it develops. The rigorously ordered pyramidal composition does not hinder the movement of the figures, and the painstaking orchestration of their gestures (the superimposition of hands and interplay of looks) takes on a new intensity in the diffuse light which softens outlines without weakening the modeling of the figures.

*: The figures’ natural poses and the omnipresence of the predominantly mineral landscape are highly innovative compared to the affected architecture and hieratic poses of the altarpieces of the period. Yet it was not until 1501, when the cartoon of Saint Anne was first shown in Florence (see INV 776) that these principles were put into practice by other artists.

*: At the apex of the pyramid sits the Virgin or Madonna whose hand is raised, palm-down, over the head of the infant Christ, as if giving him a blessing. Gabriel’s hand, which is pointing to the infant John, forms a horizontal line in the space between the Virgin’s hand and the head of Christ, as if completing an invisible cross.

*: Meanwhile the Christ Child tiny right arm is raised in a gesture of benediction, aimed at the infant Saint John, who clasps his hands in prayer. The circle is completed by the Madonna who extends her arm to encircle the head of the infant John.

*: Leonardo’s handling of light and shade – arguably his greatest single contribution to High Renaissance painting – is almost faultless. The figures project out of the darkness of the grotto, illuminated by light falling from the top-left of the picture. The resulting chiaroscuro enhances the solidity and three-dimensionality of the figures, whilst Leonardo’s mastery of sfumato ensures that the edges between the illuminated and shadowy areas of the figures’ faces and bodies are rendered with the greatest possible reality. This naturalism marks a highpoint in Leonardo’s painting, but signals his abandonment of the style of Renaissance art in Florence – that is, the expressionist method championed by Botticelli (see La Primavera (c.1482-3) or the Birth of Venus (1484-6), both in the Uffizi), in which anatomical accuracy is sacrificed for artistic effect.

*: The raised linear perspective, by which the illusion of depth is given to the painting, is created by means of a contrast between the jagged black rocks in the grotto and the hazy profiles of the mountain tops in the far distance – a not inconsiderable feat, given the narrow tonal range of the monochrome background.

*: The setting of a rocky den is a perfect image by which to evoke the notion of natural motherhood. In the candlelit church of San Francesco Grande, the glittering frame together with the dark rocks of the picture, from whose shadows the holy figures emerge, would have combined to suggest a primordial cave, an ideal setting for the mystery of the Immaculate Conception

*: fantastic quality of imagination

*: natural architectural construction in the form of a canopy

*: early use of oil painting

*: Ieo explored the form of oil painting to its full potential

*: transparent glazes and atmospheric effects

CHIARASCURO

SFUMATO

*: lack of linearity compared to the works by Botticelli

*: mysterious scene

*: secluded rocky setting, the pool in the foreground, and the carefully rendered plant life suggest symbolic meanings

*: The figures emerging from the semidarkness of the grotto, enveloped in a moist atmosphere that delicately veils their forms.

*:The fine haze of Sfumato lends an unusual warmth and intimacy to the scene. The light draws attention to the finely realized bodies of the children and the beautiful heads of the Virgin and the angels.

*: Leonardo arranges the figures into a pyramid of form, with the figures establishing a solid geometric shape in space which has the Virgin;s head at the apex.

*: As a result, the composition is stable and balanced, but the gestures lead the eye back and forth to suggest the relationships among the figures. The selective light, quiet mood, and tender gestures create a remote, dreamlike quality, and make the picture seem a poetic vision rather than an image of reality

*: the relationship between poetry and painting

Last Supper

Maria della Grazie

Milan

1495-1498

*: Leonardo also simultaneously depicts Christ blessing the bread and saying to the apostles “Take, eat; this is my body” and blessing the wine and saying “Drink from it all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for the forgiveness of sins” (Matthew 26). These words are the founding moment of the sacrament of the Eucharist (the miraculous transformation of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ).

*: Leonardo’s Last Supper is dense with symbolic references. Attributes identify each apostle. For example, Judas Iscariot is recognized both as he reaches to toward a plate beside Christ (Matthew 26) and because he clutches a purse containing his reward for identifying Christ to the authorities the following day. Peter, who sits beside Judas, holds a knife in his right hand, foreshadowing that Peter will sever the ear of a soldier as he attempts to protect Christ from arrest.

*: The balanced composition is anchored by an equilateral triangle formed by Christ’s body. He sits below an arching pediment that if completed, traces a circle. These ideal geometric forms refer to the renaissance interest in Neo-Platonism (an element of the humanist revival that reconciles aspects of Greek philosophy with Christian theology). In his allegory, “The Cave,” the Ancient Greek philosopher Plato emphasized the imperfection of the earthly realm. Geometry, used by the Greeks to express heavenly perfection, has been used by Leonardo to celebrate Christ as the embodiment of heaven on earth.

*: Leonardo rendered a verdant landscape beyond the windows. Often interpreted as paradise, it has been suggested that this heavenly sanctuary can only be reached through Christ.

*: The twelve apostles are arranged as four groups of three and there are also three windows. The number three is often a reference to the Holy Trinity in Catholic art. In contrast, the number four is important in the classical tradition (e.g. Plato’s four virtues).

*: In contrast to Andrea del Castagno, Leonardo simplified the architecture, eliminating unnecessary and distracting details so that the architecture can instead amplify the spirituality. The window and arching pediment even suggest a halo. By crowding all of the figures together, Leonardo uses the table as a barrier to separate the spiritual realm from the viewer’s earthly world. Paradoxically, Leonardo’s emphasis on spirituality results in a painting that is more naturalistic than Castagno’s.

*: Because Leonardo sought a greater detail and luminosity than could be achieved with traditional fresco, he covered the wall with a double layer of dried plaster. Then, borrowing from panel painting, he added an undercoat of lead white to enhance the brightness of the oil and tempera that was applied on top. This experimental technique allowed for chromatic brilliance and extraordinary precision but because the painting is on a thin exterior wall, the effects of humidity were felt more keenly, and the paint failed to properly adhere to the wall.

*: mathematical symbolism, psychological complexity, use of perspective and dramatic focus, make it the first real example of High Renaissance aesthetics.

*: In short, the painting captures twelve individuals in the midst of querying, gesticulating, or showing various shades of horror, anger and disbelief. It’s live, it’s human and it’s in complete contrast to the serene and expansive pose of Jesus himself.

*: As in all religious paintings on this theme, Jesus himself is the dynamic centre of the composition. Several architectural features converge on his figure, while his head represents the vanishing point for all perspective lines – an event which makes The Last Supper the epitome of Renaissance single point linear perspective. Meantime, his expansive gesture – indicating the holy sacrament of bread and wine – is not meant for his apostles, but for the monks and nuns of the Santa Maria delle Grazie monastery.

*: In most versions of The Last Supper, Judas is the only disciple not to have a halo, or else is seated separately from the other apostles. Leonardo, however, seats everyone on the same side of the table, so that all are facing the viewer. Even so, Judas remains a marked man. First, he is grasping a small bag, no doubt symbolizing the 30 pieces of silver he has been paid to betray Jesus; he has also knocked over the salt pot – another symbol of betrayal. His head is also positioned in a lower position than anyone in the picture, and is the only person left in shadow.

*: Leonardo employed new techniques to communicate his ideas to the viewer. Instead of relying exclusively on artistic conventions, he would use ordinary ‘models’ whom he encountered on the street, as well as gestures derived from the sign language used by deaf-mutes, and oratorical gestures employed by public speakers. Interestingly, following Leonardo’s depiction of Thomas quizzically holding up his index finger, Raphael (1483-1520) portrayed Leonardo himself in the The School of Athens (1510-11) making an identical gesture.

*: Laid out on the table, one can clearly make out the lacework of the tablecloth, transparent wine glasses, pewter dishes, pitchers of water, along with the main dish, duck in orange sauce. All these items, portrayed in immaculate detail, anticipate the still life genre perfected by Dutch Realist painters of the 17th century.

*: Leonardo’s meticulous crafting of The Last Supper, along with his skills as a painter, draughtsman, scientist and inventor, as well as his focus on the dignity of man, has added to his reputation as the personification of intellectual artist and creative thinker, rather than merely a decorative painter paid to paint so many square yards a day. This idea of the dignity of the artist, and the importance of disegno rather than colorito, was further developed by Michelangelo and others, culminating in the establishment of the Academy of Art in Florence and the Academy of Art in Rome.